“Should old acquaintances be forgotten, and never brought to mind? Should old acquaintances be forgotten, for the sake of old times?”

You might recognize some of those lyrics, but not all of them. If you did recognize all of them, you’re lying. This is my version, copyright Ben 2021 all rights reserved. The one you know asks about auld acquaintance and ends with its most iconic words “auld lang syne“. That’s also the name of the song, and it’s a New Year’s Eve classic. The one I led with is my rough attempt at translating it into English.

It might come as a surprise that the original isn’t English. Or you might have reasoned that “auld lang syne” is a foreign phrase, but everything else is more or less English, if a dated form of the language. I hate to bear the bad news, but you’d be wrong. The whole song, “acquaintance” and all, isn’t written in English. It’s Scots.

What is Scots?

Scots is a distinct language, one of the three cultural languages of Scotland, the other two being Scottish English and Scottish Gaelic. Scottish English is just English with a wee bit of Scottish flair and hidden behind the beautiful phonic tangles that are Scottish accents.

Scottish Gaelic, which is spoken by fewer than 60,000 Scots, is a Celtic language endemic to the Scottish Highlands. The first widely-spoken language in Scotland (as with all of Britain) was probably a Celtic language, but it wasn’t this one. This one’s a descendant of Irish Gaelic, an official and similarly-endangered language of Ireland.

Scots, though often confused with both Scottish Gaelic and English, is its own, fully separate, language. It’s sometimes called “Lowland Scots” to further distinguish it from the highland Scottish Gaelic, which itself is sometimes (confusingly) called Scots Gaelic. Though similar in name, the two couldn’t be more dissimilar. I mean — they could; they could be, like, Zulu and Chinese, but you get it. Where Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language related most closely to languages like Irish and Welsh, Scots is a Germanic language most similar to English and more closely related to Dutch and German than its highland neighbor.

Scots is actually super closely related to English. It’s distinct enough that it’s considered a language, but the two sister tongues are mutually intelligible, a linguistic term that means speakers of one language can understand the other with relative ease.

The hearing is mutual

Mutual intelligibility is a fascinating concept. For decades, Germany and Ukraine were separated by only one country, a magical land called Czechoslovakia (Germany and Ukraine are still separated by only one country, but I don’t want to talk about Poland until the end of the paragraph). When communism fell in Eastern Europe, the two halves of Czechoslovakia decided they’d grown tired of each other and got their own divorce, becoming Czechia (or the Czech Republic) and Slovakia. The Czechs speak Czech, and the Slovaks speak Slovak, but they can both understand each other fine. To a lesser extent, both can also understand their neighbors in Poland, even when they’re speaking Polish.

This brings us, though, to the even more fascinating reaches of mutual intelligibility. Czech and Slovak speakers can both understand Polish, but Slovak speakers understand it better, because while all three languages are relatively closely related, Slovak is more closely related to both Czech and Polish than those two languages are to each other.

Then there’s asymmetric mutual intelligibility. The Scandinavian languages of Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian are, just like Czech, Slovak, and Polish, mutually intelligible. And, in the same way, some are closer than others. In this case, it’s Norwegian that comes out on top; Norwegians generally understand both Danes and Swedes better than the two can understand each other. But, notably, this understanding is not mutual. Norwegians are better at understanding Danes than Danes are at understanding Norwegians, owed at least in part to a period of Danish influence on the Norwegian language. In other words, the Norwegian language includes little clues and keys to Danish comprehension that don’t exist the other way around.

There’s also a distinction between written and spoken intelligibility. French, for example, is difficult for Spanish and Italian speakers to understand when it’s being spoken, but much easier to understand in writing. This is because, while the spoken language has changed considerably in the past few centuries, its written form has not and thus speakers of its linguistic cousins have an easier time comprehending it.

On the other hand, some languages are mutually intelligible out loud but not at all on paper. The quintessential example of this phenomenon is Hindi and Urdu, the most spoken first languages of India and Pakistan respectively. The two are actually registers of the same mother tongue, a sort of mega-language called Hindustani. Hindustani has a complex history and its importance as a language is relatively recent, gaining particular prominence during the Indian independence movement. It was during that movement that the decision to split India into two countries, the majority-Hindu India and majority-Muslim Pakistan was cemented (badly, but that’s another article). As different as Hindu Indians and Muslim Indians were, they shared plenty of significant similarities, one of these being their most prominent language. Today, Hindustani is still the most important language in each country, but there’s a key difference: Indians write it in the Devanagari abugida (like an alphabet but where each symbol is a syllable instead of a single sound), while Pakistanis write it in modified Arabic. The difference between the two is closely related to their religious heritages — Arabic is the language of the Qur’an and the Devanagari script is the most common one used to write Sanskrit, the original language of the Hindu Vedas.

Hindi and Urdu speakers can understand each other when they’re speaking, but a Hindi speaker trying to comprehend written Urdu would have as much success as an American trying to understand English words rendered in katakana Japanese. They’re there, but they’re inaccessible, masked by an unfamiliar script.

The story of Scots

Compared to most of these examples, Scots is remarkably similar to English. It’s the closest language to ours by a long stretch. The next closest, Frisian, is a language spoken in the Northern Netherlands; it’s more similar than Dutch and German, but the two languages aren’t mutually intelligible. You’d have a hard time understanding a Frisian speaker unless you speak Frisian yourself. Or Dutch. Those two share some degree of intelligibility, but they’re no Czech and Slovak (mutual intelligibility goals).

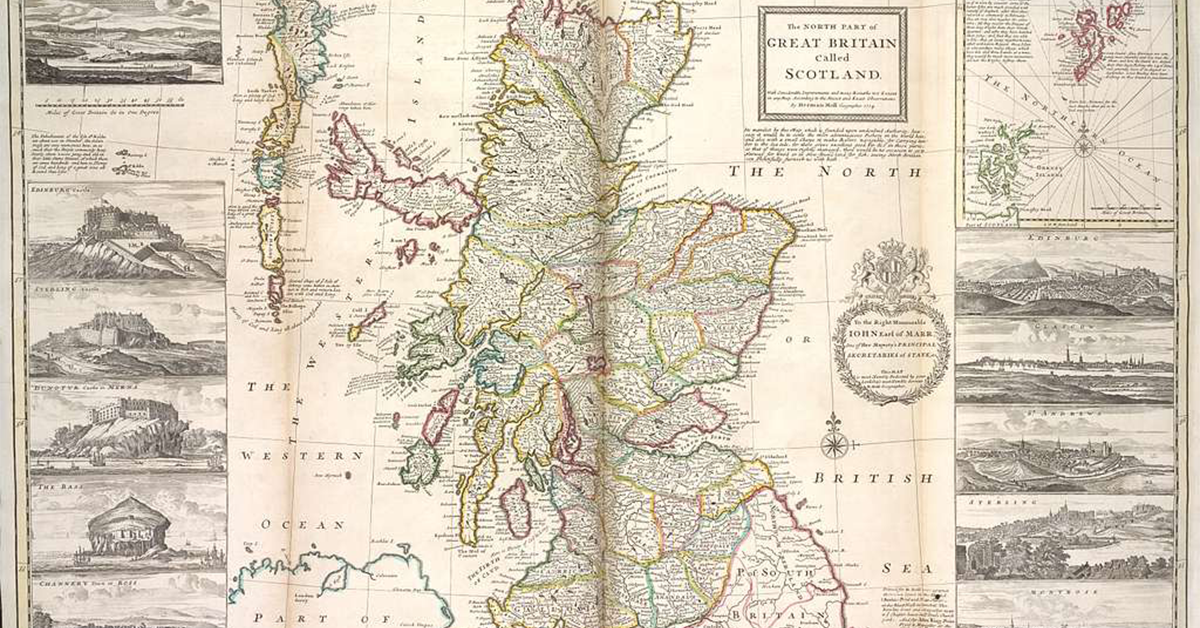

Scots and English started as one language, somewhere around a thousand years ago, when speakers of a Northern variety of English displaced Scottish Gaelic in the lowlands between the 11th and 14th centuries. Around the 15th century, it acquired the name “Scottis”, which was still used interchangeably with “Inglis” for a couple hundred years before the two were considered to have diverged enough to have become their own languages. But this divergence wasn’t the fault of Scots speakers as much as their English neighbors to the south. English was gradually morphed and altered by its proximity to and influence from languages like French, Dutch, Latin, and Gaelic. Scots took in some outside influence as well, particularly from Danish during a period of less than 200 years when Danish Viking kings ruled over much of Great Britain, but the impact was far more minor. In other words, Scots is more similar to Old English than English is.

Is it a language?

Scots and English are so closely related that I can’t blame you for asking the obvious question: what makes them different? Sure, they use some different words, but so do American and British English. We can’t understand everything a Scots speaker says, but you and I might have similar trouble understanding plain English spoken by someone from Glasgow or deep in Appalachia. What makes Scots a language and not a dialect?

That’s hard to answer. There’s an old adage that claims “a language is a dialect with an army and a navy”. It bears some truth. No one questions whether or not Danish and Norwegian should be considered their own languages. Even more notable, Croatians, Bosnians, and Serbians proudly go about speaking Croatian, Bosnian, and Serbian. But secretly? They’re the same language. Same goes for Romanian and Moldovan. Scots hasn’t had an army or a navy for a long time.

I almost wish there were a smoking gun that clearly separated Scots from English, if only for the benefit of its speakers. In reality, it’s not one huge difference that makes Scots its own thing, but a mountain of tiny differences. Scots speakers tend to use “the” ahead of seasons and weekdays (the winter, the Wednesday). They use “the day” instead of “today”. Their language has an abundance of strong/irregular plurals (we have pairs like “foot” and “feet”, “goose” and “geese”; so do they, but they’ve also got “cou” (cow) and “kye”).

On their own, each of these differences is minuscule. But in working to compile more, I quickly ran into a problem: I could not easily and satisfactorily discern what was being said in the sentences I was reading. Some words and phrases jumped out, sure, that’s the mutual intelligibility at play, but actually reading long-form written Scots is less like working out a regional accent and more like figuring out a code where not all the pieces line up the way you want them to. Here, look at these excerpts of Scots, starting with the first stanza of Robert Burns’s To a Mouse:

Wee, sleekit, cowrin, tim’rous beastie,

Robert Burns, To a Mouse

O, what a pannic’s in thy breastie!

Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

Wi’ bickering brattle!

I wad be laith to rin an’ chase thee,

Wi’ murd’ring pattle!

There’s also the incomprehensible The Wallace:

Our antecessowris that we suld of reide,

Blind Harry, The Wallace

And hald in mynde thar nobille worthi deid,

We lat ourslide throu verray sleuthfulnes,

And castis us ever till uther besynes.

Till honour ennymyis is our haile entent,

It has beyne seyne in thir tymys bywent.

Our ald ennemys cummyn of Saxonys blud,

That nevyr yeit to Scotland wald do gud,

But ever on fors and contrar haile thar will,

Quhow gret kyndnes thar has beyne kyth thaim till.

To be fair, this one was written in the 1400s, and that far back, everything is incomprehensible. For a more modern look, let’s try the opening paragraphs of the Scots Wikipedia article for Scots:

Scots (or “Lallans”, Inglis translation lowlands or Scots; “lawland Scots”, Scots Gaelic: Beurla Ghallta/Albais) is a Wast Germanic leid o tha Anglic varietie that’s spaken on tha Lawlands o Scotland an en tha stewartrie o Ulster en Ireland (whaur it’s kent as “Ulster-Scots”, “Scotch”, or “Ullans”) an tha leids o Scots Wikipedia. En maist airts, it is spaken anent tha an Inglis leid.

Up til tha 15t yeirhunder Scottis (modern furm Scots) wis the name o the Gallic, the Celtic leid o the aunshint Scots. Thaim that bruikit Scots cried tha Gaelic Erse (meinin Irish). Tha Gallic o Scotland is noo maistly cried the Scots Gallic an is yit spaken bi sum en tha western Scots Hielands an ilands. Fur tha maist pairt, Scots originatit fae tha Northumbrian variety o Anglo-Saxon (Auld Inglis), tho wi a meikle influence fae the Auld Norse o the Vikings, the Dutch an law Saxon thro troke wi (an incummers fae) tha law kintras, an tha Romance fae itse uise in the Kirk an legal Latin, Anglo-Norman an possibly Pairisian French cause o the Auld Alliance.

If you squint, you can figure out what’s being said, and it’s worth noting that there are some articles (notably “milk“) that are considerably easier to understand. But the best example I can find of Scots in modern use is a lecture by Doctor Dauvit Horsbroch:

Preservation

For most of its adult life, Scots has been an at-risk language. Its use was disavowed by the Scottish royal family (which was also, conveniently, the English royal family), discouraged or banned in schools, and demeaned academically. One academic suggested denoting Scots passages “Scots Non-Standard English – Working Class”. Might as well call it “Fake Dumb Language – Fuck You”.

We don’t have a clear way to determine what is and isn’t a language. In the absence of a ruling from on high, we have a couple of options. First, we could come up with our own boundary definitions. Mine, for example, might be “if you have to strain to understand a whole paragraph, it’s a different language”. That opens the doors to the minting of new languages en masse — is Cockney English a different language? What about African American Vernacular English (AAVE)? I think both of these are probably still too close to separate, owing to a long history of speakers having to mingle with outsiders more than the Scottish. But maybe some day.

Second, we could choose to care more about the well-being of communication than its paltry definitions. Scots has spent centuries under siege. It’s shared that status with AAVE and all dialects that come with speakers but without prestige. Once a language or dialect earns the appellation of bad or improper English, it becomes hard to disentangle from that reputation.

“Should the auld Scots leid be forgot?” was a silly way to tie this info-dump with a popular song, but it’s also a legitimate question. Scots, like its endangered brethren, is a living language whose remaining speakers are one of our last existing tethers to a trove of literature, culture, and historical content. When the last speaker of a language dies, so does the language, and so do its oral traditions.

Scots is far from the most endangered language. In 2007, the New York Times reported that the world was losing one language every two weeks. Traditions and stories, in some cases from hundreds or thousands of years ago, are disappearing faster than The Jewish Sports Review can put out an issue.

Scots has some protection from its status as a European language, which, unfortunately, lends more cultural legitimacy to its literature and poems. I wrote two years ago about the invention of the Cherokee syllabary, an impressive writing system created by an illiterate soldier. If present attempts at revitalization fail (and it is an uphill battle), Cherokee could be on its way out, sharing the fate of countless Native American languages that have fallen victim to that end.

Treating Scots like a grown-up, responsible language (with a tie and a job) is important, because it’s a reputation as a fake, lame, layabout dialect that does it damage and threatens to kill it off. If nothing else, we should be enamored with Scots for being the only language with which English is mutually intelligible, saving us from staring across the English Channel at old, dusty Frisian, wondering what could have been.

Should auld Scots be forgot? Isnae ‘t obvious? Nae, y’ wee numpty.

More

- A Scots Grammar by David Purves

- Scots language from Encyclopedia Britannica

- The Scots Language (or Dialect?!) from Langfocus