Counties are weird. These mortarless Incan bricks make up each of our states — except, of course exposure-addled Alaska with its boroughs and good Catholic Louisiana with its parishes — but how these administrative units operate is left entirely up to the states they call “daddy”. As a result, there’s not much uniformity between counties from different states. There’s often not very much uniformity between counties from the same state.

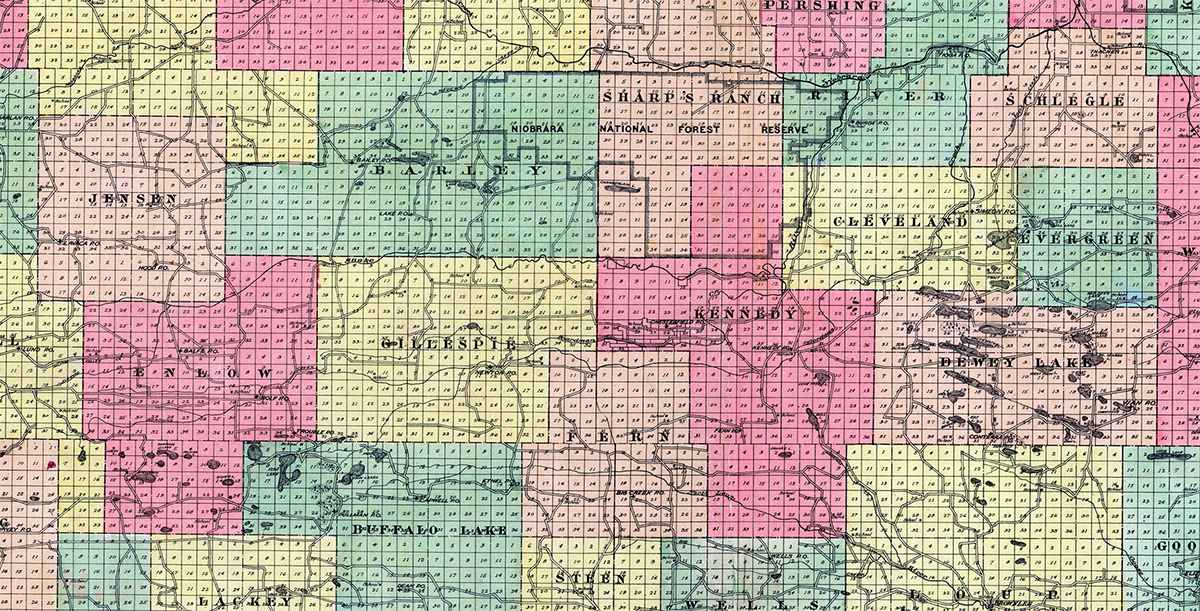

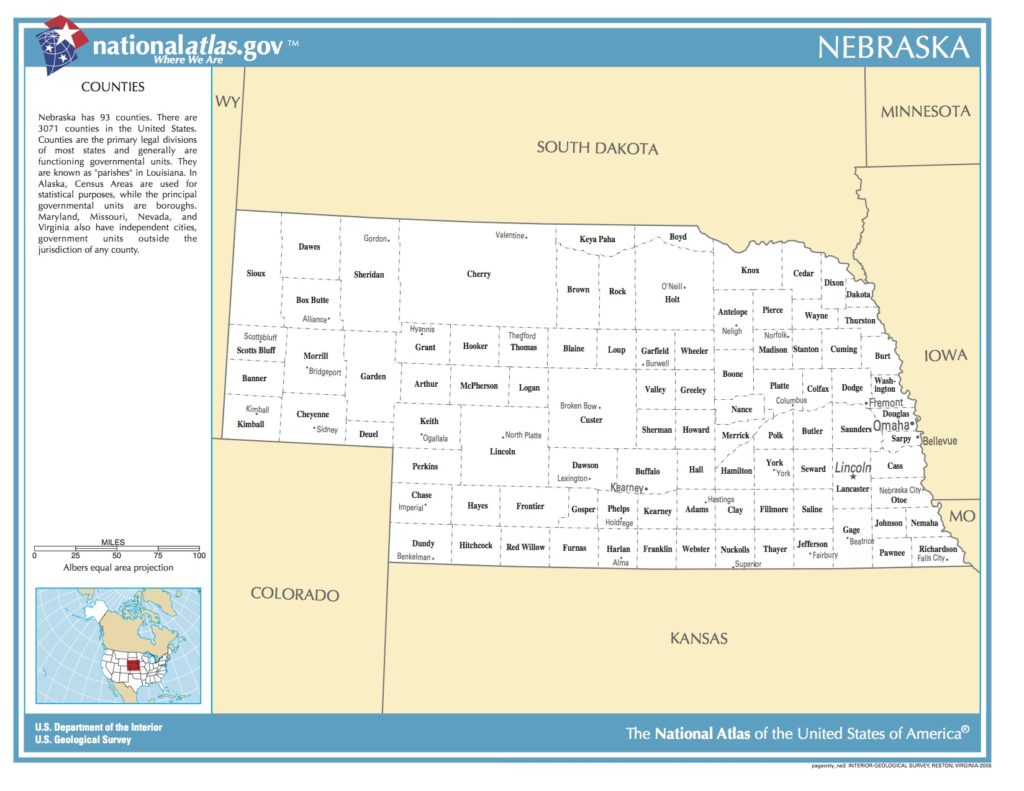

Take Nebraska. For the most part, its counties follow the Great Plains guidelines for what a good county should be: as close to quadrilateral as possible and neatly lined up shoulder-to-shoulder with their siblings. The closer we get to a waffle iron the better. But just as every class of nice, proper children has an outlier ne’erdowell who eschews homework in favor of posting memes about how girls only like guys who treat them like shit, Nebraska has its own class of geographical rebels. The worst of these offenders are Cherry, Custer, Lincoln, Holt, and Sheridan counties, each of which lays claim to its own sprawling expanse of territory like an agoraphobic steppe warlord.

Even the smallest of these counties, Holt County, is bigger than the state of Rhode Island, but it and its fellow giants pale in comparison to the behemoth that is Cherry County. With an area of just under 6,000 square miles, Cherry County is physically larger than three states: Rhode Island, Delaware, and Connecticut. If you forced the fifteen smallest counties in Nebraska to put aside their disagreements (corn vs. soybeans) and unite as one, they still wouldn’t be as big as Cherry County.

So why is Cherry County so massive? It’s kinda hard to tell. It’s easy to be dismissive and content to leave it at population density—fewer people live out west in states like Nebraska, so bigger counties there end up covering populations comparable to those serviced by the smaller counties out east.

It makes sense at first: western states like Alaska, Montana, and Wyoming are massive but sparsely populated, while eastern states like New Jersey and Connecticut cram lots of people into significantly more constricting borders. More people, more counties, fewer people, fewer counties.

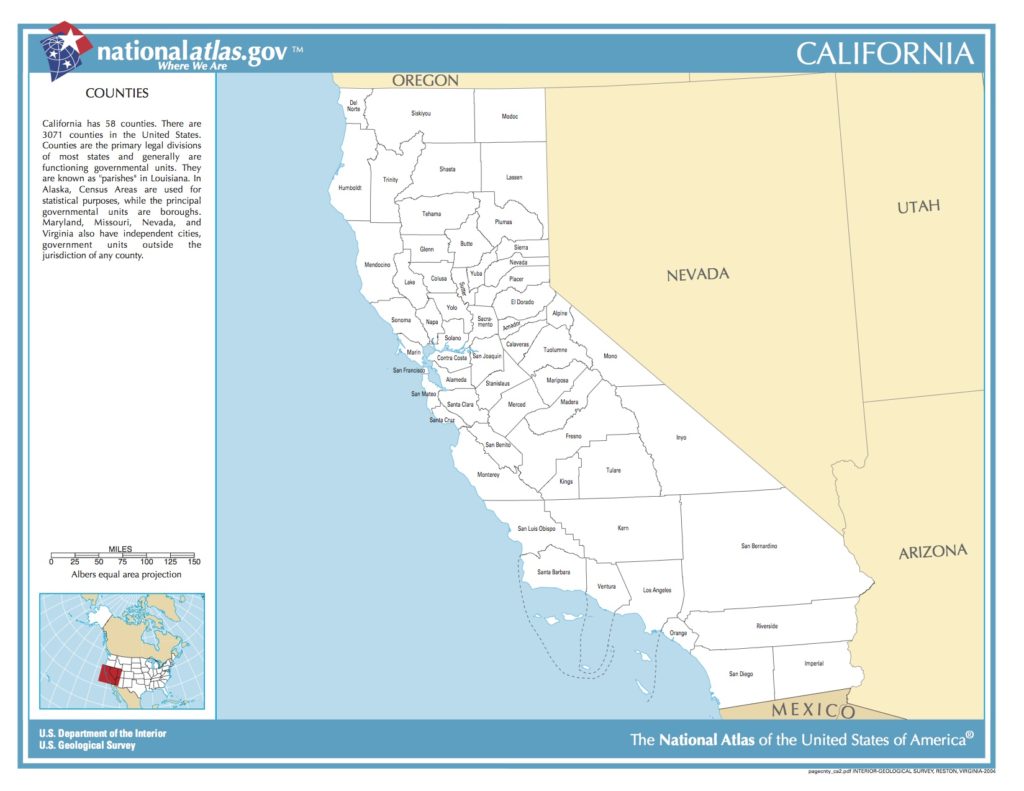

But we don’t have to look far to find exceptions to that rule. California, a western state, follows the “fewer counties out west” rule, but the populations its counties bear are supermassive. Los Angeles County is the most populous in the nation, hosting the entire population of the country’s second largest city and adding an extra five million for good measure. In fact, this single county claims a population higher than all but ten U.S. states.

My native South Dakota, a sparsely-populated and lawless wasteland packed into a four-year-old’s first draft of a rectangle, claims sixty-six counties. Meanwhile, extremely populous California has only fifty-eight.

Cherry-picking

Looking more closely at Nebraska, we see the same story in microcosm. With a population of around 5,000, Cherry County is a far cry from Douglas County (home of Omaha) and its half-a-million citizens, but forty-two of Nebraska’s counties have even fewer people. Twelve play host to less than a thousand.It turns out that the most accurate answer to the question “why is Cherry County so big?” is that so far, no one’s managed to make it small.

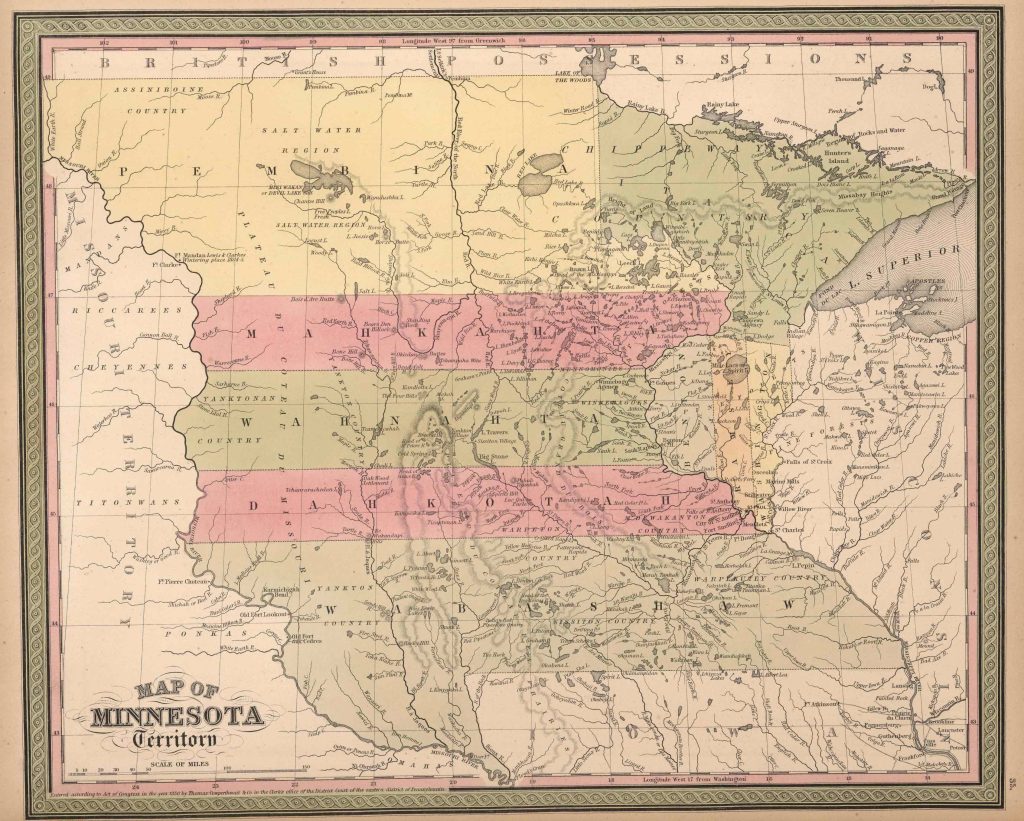

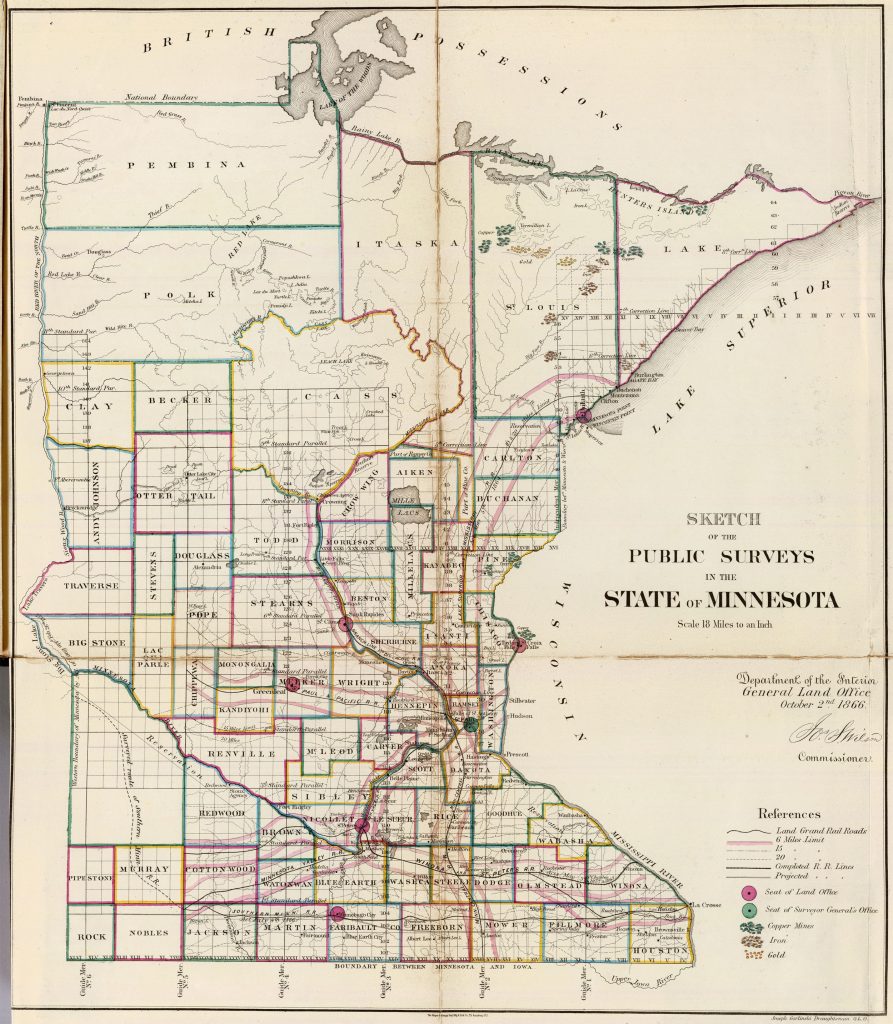

Back in the 1800s, when the regions of the United States west of the Mississippi River underwent an explosion in White settlement (weird that no one else was interested), states gradually allotted land and delegated administrative control to local governments better equipped to handle matters of small-scale administration than the often faraway state governments.

Counties started big and few but became smaller and more plentiful as more settlers flooded into the states, which made operating littler counties more viable. While cities and those rural areas more conducive to farming attracted more settlers and grew faster, mountainous regions and places with poorer growing conditions lagged. A size disparity was born. The same sort of disparity we debunked above as the cause for Cherry County’s extreme girth.

Despite adding nearly a million people in the same timeframe, Nebraska hasn’t added a new county since 1913. My home state of Minnesota tells a similar story, not having minted a new county of its own since 1923. As a result, Saint Louis County, the home of Duluth, is twice as large as the next largest county despite also being the sixth most populous. This Northern borderland behemoth was created in 1855. It lost a little of its land to neighboring Carlton county in 1857, but it’s been the same since then. Unbothered, unchanged.

So where’s the disconnect? If better-settled regions tended to support smaller counties, why don’t Nebraska’s (and America’s) counties follow the trend?

The best answer? People stopped caring. According to Visual Capitalist, the United States in 1790 had 270 counties. By 1850, that number had ballooned to 1,621. Come 1920, the country boasted 3,041 second-level subdivisions. Today, the number is 3,142. That’s just over 100 new counties since World War I. By contrast, the United States population has tripled in that same timeframe. Counties just haven’t kept up.

For what it’s worth, interested parties did at one time try to split Nebraska’s Cherry County into smaller pieces. According to History Nebraska, a ballot measure supported by the local newspaper, the Cody Cow Boy, proposed to create five new counties from the ashes of the old colossus. The Cow Boy (spelling theirs, ostensibly in reference to a juvenile minotaur) argued the plan would reduce transit times and increase property values around the five new county seats of government. Against their expectations, when election day came in 1911, the measure failed by a significant majority. Cherry County’s citizens weren’t interested in further division.

They followed a trend growing evident nationwide. After the Great Depression and the second world war, interest in smaller counties waned significantly. It’s not hard to see why: Americans were seeing a diminishing necessity for extremely-local government. As technology progressed and Americans became better able to afford cars and other means of rapid transit, the need for a county courthouse within a day’s ride on horseback deteriorated.

But while county creation slowed pretty substantially over the last century, it clearly hasn’t stopped altogether. The most recent addition to the list of U.S. counties was Colorado’s Broomfield County, created in 2001. This, like many other recent county mintings, was done to clean up a mess caused by Broomfield’s awkward masculine sprawl spreading it between four separate counties.

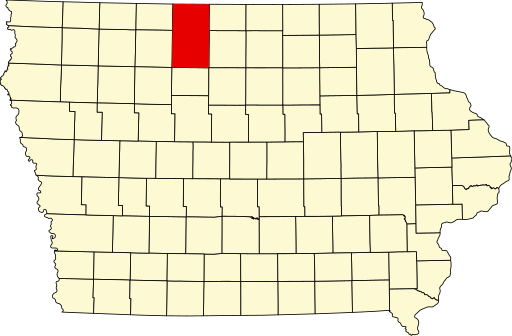

The Hungarian Conquest of Iowa

Of course, the forging of new counties is sometimes offset by the deletion of others. Iowa’s northernmost counties are divided into two mostly-neat rows in a harmony totally destroyed by the freakishly-tall Kossuth County. The county, somewhat bizarrely named after the exiled Governor-President of the Kingdom of Hungary who aroused Beatlemania-esque fandom across the United States in the 1850s, doubled in size when it ate its southern twin, Bancroft County, in utero just six months after both had been conceived. (County gestation takes significantly longer than human gestation, so this isn’t as fucked up as the timeline implies).

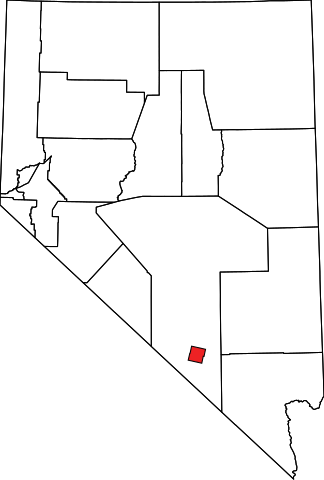

There’s no evidence the terminated Bancroft County played host to any settled population at the time of its deletion, but the land was at least intended to be governed by the people who would eventually live there. The same can’t be said about Nevada’s Bullfrog County.

The Steaming Pile of Bullfrog

A diamond spliced from the state’s grotesquely-shaped Nye County in 1987, Bullfrog County’s population, through all of its two-year existence, never grew past zero. The county wasn’t meant to be lived in; it had been purpose-built for maximal chicanery. The smallest of Nevada’s counties by a considerable margin, Bullfrog County conveniently surrounded the land the United States government had selected as the location for its premier nuclear waste storage site. Hot on the heels of the Chernobyl disaster and not eager to entertain the idea of the disposal site or its effects, Nevada’s government instead created Bullfrog County as a means of rendering the site untenable by setting absurdly high property taxes paid directly to the state government.

What was meant to be a totally epic and rad middle finger to the federal government ended up a total clusterfuck for the state of Nevada. Despite the intention being that Bullfrog would act as a cardboard Potemkin county for the purpose of shooing away investment by the Department of Energy, Bullfrog County was, by law, a real, functioning county. And as such, it was required by the Nevada state constitution to provide justice and services to the people in the county. Nevada didn’t sweat that requirement—there were no people in the county. Unfortunately, in the end, that stipulation ended up being Bullfrog’s undoing. The state’s Supreme Court determined that Bullfrog, unable to adequately represent its citizens (by virtue of having no citizens), was unconstitutional. It was dissolved in 1989, just two years after its creation.

Decades before aversion to nuclear power led to the creation of Bullfrog County, attraction to the power of the atom precipitated the founding of another county in a different desert on the other side of the Rocky Mountains.

Remembering Los Alamos

In 1943, the United States government started building a laboratory in New Mexico. Forty minutes out from Santa Fe, the lab was originally known only by the name of the clandestine operation it housed: “Project Y”. The moniker was secretive, and so was the work. It was here that scientists designed and developed the first atomic bomb.

Originally an offshoot of the larger Manhattan Project, the Project Y laboratory at Los Alamos continued to grow in size and scope following the end of World War II. The land and surrounding towns, formerly owned wholesale by the U.S. government, were returned to New Mexico in 1949. Rather than reincorporate the ceded land into the counties it had been spliced from, the state opted to create an entirely new county, named after its largest town, Los Alamos. The laboratory had by then taken on the same name.

The Los Alamos lab is one of the country’s most esteemed scientific institutions. Its first director was J. Robert Oppenheimer of “now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds” fame. If you’re more a fan of fake history than real history, this was the lab Breaking Bad’s Walter White worked at before he went into private practice.

(The previous paragraph serves as an uncomfortable window into my writing process; at the time I started this article, J. Robert Oppenheimer wasn’t the subject of one of the biggest films of the past year.)

Today, Los Alamos is one of the wealthiest, best educated, and healthiest counties in the United States. Those labels sound pretty impressive as long as we conveniently forget that the county was purposefully populated by well-educated recipients of bountiful government contracts.

There’s clearly a lot to write about the history of U.S. counties. I haven’t even brought up that their very name implies that they’re all ruled by counts, the noble underlings of the kings overthrown two hundred and fifty years ago. Maybe Alaska’s onto something after all.

But if we wanted to render everything short and sweet and make you feel like you wasted the ten minutes you spent reading this article, we can sum it up as follows: throughout the 1800s, counties metaphorically exploded onto the map. By the 1940s, technological and social advances and the threat of war had them exploding for real.

Images

- Public domain except where otherwise noted

- Otherwise noted: Map of Nevada highlighting Bullfrog County.svg by Wikimedia user Spaceboyjosh

- Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Read More

- Bullfrog County, Nev., (Pop. 0) Fights Growth by Thomas J. Knudson for The New York Times

- Bullfrog, Nevada : Empty County to Croak Unless It Goes to Waste by Charles Hillinger for the Los Angeles Times

- Cherry County Divided from the Nebraska State Historical Society

- Curious Iowa: How were Iowa’s 99 county borders determined? by Bailey Cichon for The Gazette

- Los Alamos from Encyclopedia Britannica