Six hundred years ago, the color orange didn’t exist. At least, not by that name. Everything that is orange would have looked the same; sunsets, autumn leaves, …oranges, they all would have been just as orange, but no English speaker would have had a single word to describe them all. The best they could have done would have been “yellow-red” (or its Middle English equivalent, “ġeolurēad”). We had cannons, the printing press, and ships that could sail across oceans. But we didn’t have orange.

That a language born in the dreary English countryside would take its time coming up with a name for a particularly bright and audacious color might not floor you; more interesting is that most languages six hundred years ago probably didn’t have a word for the color “orange”, and that plenty of languages spoken today still don’t. More still, orange isn’t alone; plenty of colors, from yellow to blue, are missing from the lexicons of hunter-gatherers and epic poets alike.

I know “history of orange” sounds like it should be a quick few paragraphs in total, and maybe there are writers out there who can accomplish that. But if you’re in for the long haul, a thicker helping of history ladled out by a guy still recuperating from a six-party series about the dead king of a country that no longer exists, we have to start with the history of color itself.

How many colors are there?

Most English speakers grow up learning the immutable truth that there are somewhere between six and twelve core colors, depending on your stances on indigo and shades of gray (I’m of the opinion that the existence of “indigo” is a holdover from the MK ULTRA days; if it’s such an important color, why do we have it drilled into our heads in kindergarten only to never hear about it again?), but many languages divide the palette into fewer categories, some as few as two.

Academics who study the language of color land on eleven core colors for English speakers (black, white, gray, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple, pink, and brown). The Russian and Korean languages boast twelve core colors, whereas Yup’ik, a language spoken by a people native to Alaska, has only five.

When we divorce color from our preferred categorizations, we understand that it’s more a continuous spectrum and less rigid blocks of hues. There are tons of distinguishable colors that we choose to label “blue”, some greener, others purpler. It’s for our own convenience that we draw them up into neat little boxes. Computers might be able to scan an image and identify the color of a wall as “#B22222 Fire Brick” or “#7A554D Doo Doo Dirt“, but early (and current) humans lack that level of background and acuity and usually opt to settle for “red” or “brown”.

Knowing that other languages do things differently, that they draw more or fewer boxes around the color wheel than we do, we might assume that where they draw their borders is arbitrary. If two languages both have three core colors, we might expect that one of them chose red, blue, and green, while another went for white, black, and yellow, dependent on some factor like environmental availability or aesthetic preference. But we’d be wrong.

Existing research suggests that, if a culture has only two colors, those colors will always be black and white (or, more accurately, light and dark). If they have three core colors, they’ll always be black, white, and red. No exceptions. So our proposed languages where speakers only label objects red, green, and blue, or white, black, and yellow? They don’t exist. They can’t. That’s not all, though; the pattern goes further.

There’s a little bit of a hiccup at four. After a mandatory journey from black and white to red, languages get a choice between yellow and green. Choose carefully, but not that carefully; the other one comes next. Then, and only then, will they move on to blue. After that, it’s a crapshoot, at least as far as current research tells us. But what we’re certain about so far is that languages develop words for color in the following order: black and white, then red, then yellow or green, then green or yellow, and then blue.

This law holds true everywhere, from the Indo-European languages of Eurasia to the Bantu-derived tongues of sub-Saharan Africa to the native peoples of the Americas and Oceania. Linguists have thus far been unable to identify a language that does not follow this pattern of color acquisition. (If you can find one, I’ll delete this article.)

Modern English has eleven core colors, but the languages that made way for it, the Middle English, Old English, West Germanics, and Proto-Indo-Europeans of history, certainly had fewer. You don’t need to trust that. If you’re enough of a nerd, you can see it.

The Odyssey

The example that launched a thousand studies is one of the western canon’s oldest surviving works of fiction, Homer’s The Odyssey. If you’re like me and had to read The Odyssey in school, you remember remarkably little, because you spent most of your time illegally exchanging notes with classmates (the statute of limitations expired this last academic year) and making fun of how the translator couldn’t land on a spelling for “Cyclops” (surprise second act revelation: I wasn’t cool in high school). But if you’re unlike me, maybe an astute student who didn’t have to be taken out of class to be told to take books more seriously, you might have scratched your head at Homer’s quirky relationship with color.

Odysseus, the story’s namesake and hero, is a sailor who spends most of his page-time on or adjacent to the ocean. Homer, if he existed at all, was Greek, and probably wouldn’t have lived particularly far from the open waters of the Mediterranean himself. It’s odd, then, that the only time he identifies the color of the water is in a passage where he calls it “wine dark”. There’s no “wide blue waters” or “azure expanse”. It’s “wine dark” once and that’s it.

The ocean’s not the only thing Homer compares to the color of wine; he applies the same treatment to oxen, which, depending on species and perspective, range in color from white to black to brown, but not wine color, and definitely not the same color as water.

Homer’s weird color habits don’t stop there. Odysseus, by all accounts a dark-haired man, has his locks described by Greece’s favorite epic poet as “hyacinth”. Homer also uses the Greek word for “green” to describe peoples’ faces, tree branches, and (sickeningly) honey.

If you’re enough of a nerd to get this far, you’re following me. If you’re too much of a nerd, you’ve hit a hiccup: these sound like the chromatic misunderstandings of a blind person. It’s appropriate, you’ve identified, because Homer (assuming he existed at all) is usually understood to have been blind.

But blindness or no, while Homer was the first of the ancients to be called out for his awful color sense (in a sprawling set of tomes published by a man who would later become Prime Minister of the United Kingdom), he was far from the last. Lazarus Geiger, an early German student of language active in the mid-1800s, read through scores of ancient texts, from the Bible in its original Hebrew to the Sanskrit passages of the Hindu Vedas, and identified the same pattern of painting with a stiflingly limited palette.

When he first noticed that pattern in Homer’s work, Gladstone got way ahead of himself and used it to suggest that all ancient Greeks were colorblind. While many of his contemporaries were critical of his overall reading of Homer, the idea that lesser-developed cultures were unable to see color as well as their better-developed counterparts spread like wildfire. If that’s a hard concept to swallow, remember that this is around the same time that educated people are going nuts for Lamarckian evolution, the (Darwinian fan-fiction) idea that giraffes have long necks because a daddy horse stretched his neck so far that his kid inherited it, and that any animal with the appropriate amount of grit and gusto can do the same. Pour one out for the kids of those guys on YouTube who tattoo their eyeballs. The sins of the father and all.

But while folks will stay muddled in this quagmire of causality for a while, they’ll make notable gains elsewhere. Geiger’s studies of the Bible and Vedas are expanded to include further-out sources like the Sagas of Iceland and the Koran.

By the 19th century, early linguists were ready to go even further. By interviewing members of isolated tribal groups from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, they identified the same white-black-red-yellow/green-blue procession of color development. Up until then, most of them still believed that cultures that have fewer words for color were simply unable to see the ones they didn’t have vocabulary for. The bulk of available literature is expanding, but new entries still come with a pretty massive asterisk; it’s all too easy for these guys to assume that a culture that doesn’t have a word for “green” can’t see green, or at least can’t at all distinguish green things from red. If you squint, the logic looks reasonable, but the real allure is that the idea that Europeans have better vision than the backwards natives of other continents is simply the latest piece of 1800s evidence that white people monopolize the ladder of cultural development. But that’ll change soon.

One of the engines behind the coming shift is a team of German anthropologists who make the long trek to spend time with an African tribe from Sudan, testing first their vocabulary and then their ability to distinguish colors. I’d be willing to commend the team for their dedication to making the arduous journey up the Nile and for immersing themselves in the local culture, but I’d be getting ahead of myself. Our Germans’ faraway destination wasn’t Sudan, but Chicago. The African tribe is… in a zoo. Because it’s the early 1800s, and we’re still doing that. (We won’t stop doing it for a while.)

After a few major strides, the study of color naming goes dormant for the better part of a century before it’s dusted off and picked up anew by linguists Paul Kay and Brent Berlin. Kay and Berlin revitalize Geiger’s theory for the 20th century and conduct the first wide-ranging study of both isolated and cosmopolitan cultures to verify its universality. Their findings, taken from an extraordinarily diverse selection of humans living in cities, villages, and nomadic bands scattered across all settled continents, provided ironclad support for the universal color order hypothesis. Not everything the two proposed holds up today, but their central finding, the universality of the order in which we develop words for color, stands tall.

All languages develop words for color in the same(ish) order, but the exact “when” of most of these developments is hard to track. If we’ve figured out exactly when colors like “blue” entered the English lexicon, the truth’s been hidden from me. A trip to Google Books’s Ngram viewer suggests that “purple” starts its rise around the early 1500s. It’s around that same time that we find the earliest documented use of the color “orange”.

Orange

It’s the fruit that came first. Originating somewhere in Eastern Asia, the most prolific of citruses spread first to South and Western Asia before crossing the Mediterranean, climbing up France, and making itself uncomfortable in the inhospitable, queue-laden climes of the British Isles. As the fruit’s territorial range grew, so did its mark on local languages. Persian, one of the first Indo-European languages to get ahold of it, called it “narāng”. Borrowing from their neighbor, Arabic went with “naranj”, and Spanish the similar “naranja”. French, ever different, eventually corrupted it to “orange”.

By 1500, the orange had been at home in Moorish Spain for four or five hundred years. The sea demon Christopher Columbus may have brought it with him on an early voyage and ordered one of his goons to plant it on the island of Hispaniola. The modern sweet orange, itself a hybrid of the classic mandarin orange and pomelo fruits, was still centuries off, but the orange had carved itself a place in and on European tongues.

Still, as familiar as they’d grown with the fruit, the people of Europe still wouldn’t be able to wrap their heads around orange the color until closer to 1502. It’s hard to determine exactly when English speakers first made that genius leap; all we have to go on is the written record, and England’s peasants won’t get hooked on phonics for another few hundred years. So while it’s unlikely to be the first actual usage of “orange” in our desired context, we have to track the word’s written origin as far as we can, to an order of orange-colored cloth for the queen. It’s hard to know how long people had been saying “orange” (and struggling to rhyme it) before anyone bothered to write it down.

Orange had made a name for itself, but the height of its fame was yet to come. Across the English channel, another European monarch sees the queen’s single order of orange cloth and raises her ten million.

The Dutch Connection

Patriotic Americans love red, white, and blue. So do the British; their flag is made up of the same core colors. So do the Russians, and the French, and the ever-patriotic Luxembourgish. Actually, a lot of flags adhere to that trend. The Australian flag is one of them. But when supporters of the world’s largest island’s national soccer team take to the field, it’s not red, white, or blue they’re boasting, but green and gold. Their distant neighbors to the southeast do something similar. New Zealand’s flag is incredibly similar to Australia’s, being just two stars fewer and a bit more colorful. But when the national rugby team plays, the observing Kiwis make up a sea of black.

In both cases, these choices of color reflect a complex chain of cultural history that can be ignored completely by reading a paragraph about local sports fandom. In Australia, green and gold are heralded as national colors based on the country’s designated national flower, but it was the soccer team that used the colors first — the explanation was added afterward. In New Zealand, the importance of the color black is, in a way, a trait inherited from the country’s native Maori. But another, perhaps more genuine, explanation is that the country’s fascination stems mostly from its love for rugby. New Zealand’s population is comparable to my home state of Minnesota, where, during football season, purple takes on a particular prominence. Prince aside, purple wasn’t a cultural mainstay of the state before the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings chose it.

Across the Atlantic, it was another prince who gave rise to another national hue. Just like the Americans, British, Russians, Australians, Kiwis, and French, the flag of the Netherlands is made up of three colors: red, white, and blue. But when the Dutch national football team plays, its supporters are united in a sweeping collective wardrobe of orange.

Unlike the Australians and New Zealanders, it’s not sport that preempted the color choice. The Dutch connection to orange goes back further.

In the early 1500s, the Netherlands were ruled by the Kings of Spain, a branch of Europe’s Habsburg family known for giving Game of Thrones‘s Targaryens a run for their money with their penchant for fancy incest. Unhappy with their political domination by kings separated from them by all of France, the Dutch rose up in a series of rebellions that today we group under the umbrella label “The Eighty Years’ War”. The earliest of these rebellions were led by William the Silent, a Dutch Nobleman and scion of the House of Orange.

Its full name is the House of Orange-Nassau, paying homage to its parent house (that one now the family in charge of the much smaller Luxembourg). The other half, the one we’re concerned with, takes the part we’re even more concerned with (“Orange”) from a small county and its associated town in southern France, from whence the family originally hailed. Notably, though, while the Dutch “Orange” and the English “orange” both pass first through France, the two words aren’t actually related. The French town of Orange was once the Roman settlement of “Aurasio” or “Aurasion”.

Despite their disparate origins, the two oranges became fast friends, the House of Orange adopting its homonymic doppelgänger as its official color. (I can’t exactly blame them.)

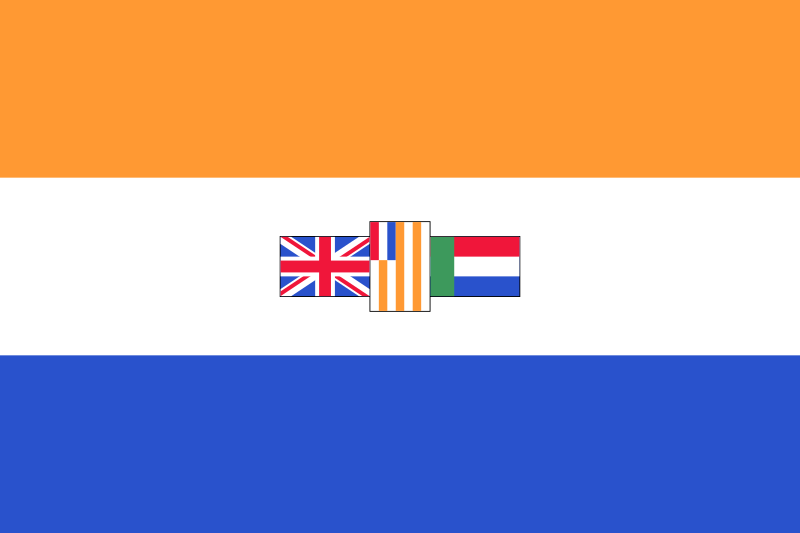

When it came time to pick a flag for the nascent Republic of the Netherlands, the government chose colors associated with their early prince: white, blue, and orange.

It’s a bold move, but one that resonates hard with the Dutch. There’s the obvious soccer connection, but my favorite story of the Dutch love for orange has consequences that go way deeper. When they first reached European farmers, carrots were purple. Genetic variations that appeared over time introduced brighter yellows, but it wasn’t until the Dutch, armed with their own weird patriotism, stepped in that their modern orange variety was born. From there, orange carrots spread quickly around the world, and potentially for the better; it’s the orange ones that come loaded with beta-carotene antioxidants.

Today, the Dutch flag is a much more conventional (boring) tricolor, having eschewed its prototypical orange for a more worldly red. Stories attempting to account for the orange-red transition vary, but my favorite is the one that alleges that the orange pigment they chose darkens to red naturally over time and that the Dutch government simply got tired of replacing their old flags with new ones.

In both its incarnations, the Dutch flag may have been the most influential flag in the history of the world. The red-white-and-blue tricolor of today is said to have inspired the modern French flag, whose designers attribute wholly French reasons for its creation but credit the Dutch for first identifying red, white, and blue as the “colors of liberty”.

Nearly a century before the architects of the French flag honored its Dutch progenitor for its trichromatic depiction of liberty, Europe’s most autocratic leader was interpreting the flag slightly differently. The Tsar of Russia, Peter the Great, had a thing for modernization; Russia was falling behind, and if it wanted to be a real European power, it would have to start emulating everyone else.

The cornerstone of Peter’s modernization campaign was the upgrading of the Russian navy, a process he started by purchasing and inspecting newly-built ships from the more advanced navies of the west. The most popular story of the Russian Flag’s birth goes that it was one of these ships flying the Dutch tricolor that inspired Peter to rearrange the colors and build a Russian tricolor of his own.

France and Russia were two of the first countries to owe homage to the Dutch flag, but they wouldn’t be the last. Russian championing of pan-slavic identity led to a widespread copying campaign radiating from the Prague Slavic Congress of 1848. Delegates to the Congress identified the three colors as a pan-slavic emblem, leading in part to their adoption on the historical flags of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, and on the modern flags of Serbia, Croatia, Czechia, and Slovakia.

To the chagrin of pan-Slavic globalists everywhere, this article isn’t supposed to be about red, white, and blue. It’s about orange. And while that color’s been totally absent from the Dutch flag for nearly a century, it has a vexillological legacy of its own.

South African Boerdom

The Dutch East India Company established one of the first permanent European settlements, the Cape Colony, in today’s South Africa in 1652. To the disappointment of the company, whose primary, secondary, and tertiary interests were making money through Asian trade, the colony soon attracted a population of European settlers looking for brighter horizons for themselves and indifferent to the potential plight of the people they might supplant.

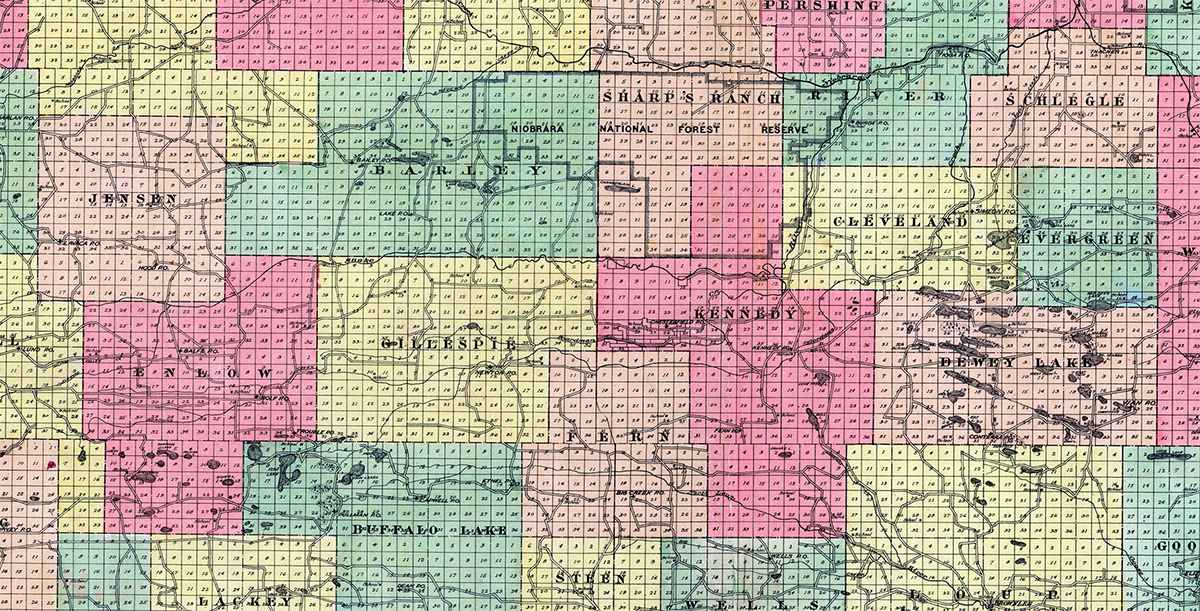

Unsatisfied by the boundaries enacted by the Dutch East India Company, settlers of primarily Dutch origin started expanding beyond into inland territories then still held by native Africans. These independent settlers, known as “boers” (the Dutch word for “farmer”) cast aside their Dutch citizenship and founded the Orange Free State and the Transvaal Republic in eastern South Africa. These independent republics would go on to cause an insane amount of strife, first (and continuously) with native Africans, then with the Dutch, and finally with the British, who took control of the Dutch East India Company’s African holdings during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s. It’s hard to argue that anything but this era of discord would be their most significant legacy.

…but in distant second: their flags. When South Africa gained its eventual independence from the British empire, it threw off the yoke of the British ensign and promptly redisplayed the orange collar of its previous overlords. The base of the flag was a carbon copy of the old, out of use Dutch one with the flags of Transvaal and the Orange Free State superimposed on the white band. I guess they didn’t totally throw off that yoke of British colonialism, as the union flag was there too. In all, it was an ugly flag, one that would become synonymous with the apartheid government it represented.

Further away, the Dutch mark on other flags is less lamentable. Before the largest city in the United States was the British-named New York, it had been a Dutch holding, the capital of the province of New Netherland known then as New Amsterdam. Echoes of this brief era of colonialism reverberate still in New York, from neighborhoods like Harlem (named after the Dutch city of Haarlem) to the borough of Brooklyn (after the much smaller town of Breukelen). But the mirror that concerns us most is the flag of New York City, a vertical tricolor composed of blue, white, and orange with a(n ugly) city seal stamped on the white.

The color orange also makes its way into other local flags, like the borough flags of Manhattan and the Bronx, the city banner of Albany, and the standards of Westchester and Orange counties. The Dutch Colony of New Netherland lasted less than sixty years. Its cultural influence stretches slightly longer.

Beasts of England, Beasts of Ireland

So far, every orange flag we’ve learned about owes its identity to the Netherlands. But what about the most well-known of them all?

In 1690, the forces of James II (or VII, depending on who you ask), King of England, Scotland, and Ireland were defeated at the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland by those loyal to the new king. James was Catholic, the last in a long line of British Catholics who jockeyed for authority against their Protestant rivals, and the last Catholic leader to ever wear the crown. This was the Glorious Revolution, a protestant-led rebellion that sought to overthrow and replace him with a leader not in communion with the Roman Catholic Pope. After a search of potential throne-sitters, they chose his own daughter, Mary. We’re gonna have to soar right past the moral conflict that is killing your dad so you can be queen; Mary’s down to clown.

Of course, there is one snag: Mary Stuart had recently left England to be with her new husband, William III, Stadtholder of the Netherlands and head of the House of Orange-Nassau. (You know them, right? Took us less than three paragraphs to get back to our boys.) The great-great-grandson of William the Silent, William shared his ancestor’s favor for his house’s unavoidable hue. To this day, many still know him as William of Orange.

After their final victory on the Boyne river, William and Mary shared the crown until Mary’s death in 1694, after which William reigned as the sole King of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

The protestant resurgence in William’s adoptive Great Britain brought with it a period known as the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland, during which prominent protestant nobles took more and more positions of power in the traditionally-Catholic country. Owing homage to the man whose rule brought them to that prestige, these Irish protestants also started to identify with the color of their sovereign, orange.

Meanwhile, many Irish Catholics grew resentful of their Protestant overlords, who instituted systems of tenant farming and brutal leadership that led to catastrophes like the great Irish Potato Famine. The protestant Irish connection to orange is more esoteric to Americans like myself, but I doubt I have to explain the Irish Catholic attachment to green.

This Protestant-Catholic dispute, long boiling by the time William brought it to a new height, would only continue to heat up, leading to a series of rebellions and, eventually, the Troubles of the late twentieth century.

But when Ireland finally gained its independence from the United Kingdom in 1921, the flag it adopted was one symbolizing unity: the green of Irish Catholics and the orange of Irish protestants, separated by the white banner of the truce and the peace that existed between them.

A Surplus of Citrus

The legacy of Dutch orange is a complicated one. In the domains that once proudly bore their flag, modern opinions vary from disinterest to hatred to nationalist fervor, the latter two usually connected. In South Africa, the old South African flag has become a symbol of the apartheid regime that kept the country’s native Africans subjugated beneath a European-descended white elite until the end of apartheid in the 1990s. Viewed by some white South Africans as a symbol of their heritage, somewhat in line with the confederate battle flag in the United States, public display of the “apartheid flag” was banned in 2019.

In Northern Ireland, the part of the island that stuck with the United Kingdom when the rest became independent, parades known as “orange walks” are held every summer by orange-clad members of the dominant protestant group. The parades commemorate William of Orange’s victory over James, and have drawn criticism from Irish Catholics who see them as divisive and offensive.

Even in the Netherlands, where orange remains a celebrated color, the old orange, white, and blue Prince’s flag has soured in the eyes of some since it’s been adopted as a symbol of the country’s far right.

Ġeolurēad

In its 500 years as a shade identifiable to the tongues of Western Europe, orange has put it’s work in, muscling its way into the old boys’ club and becoming a constituent color of an indivisible rainbow. Today, we color traffic cones and construction barriers orange to stand out against their backgrounds. Hunters wear orange for its dual utility as a highly-distinguishable color for humans compared to the green backdrop of nature, one that, importantly, won’t clue in their prey, deer and other ungulates who, unlike the Greeks, are green-orange colorblind. Taking inspiration from the chromatic confusion of the Dutch and Australians, the “black boxes” that store airplane data safely in the event of a crash are not black at all, but orange to make them visible among the wreckage.

Even with all the ground “orange” has covered, it still lags behind in contemporary speech; people with orange hair are called “redheads”. Orange foxes are “red foxes”. Mars is “the red planet”; go ahead and give it a Google. Refresh your brain.

It’s easy to take for granted the building blocks of human knowledge that we first stomach before we can write our own names. But every word we use was once an invention, some more stunningly recent than others.

Read More

- Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution by Brent Berlin and Paul Kay

- How colors get their names by Claire Bowern for PBS News Hour

- How did carrots become orange? in The Economist

- The Secret Lives of Color by Kassia St. Clair

- Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages by Guy Deutscher