In March, the Summer Olympics were postponed for the first time in the event’s history. The Olympic games have previously been cancelled, but never moved. Now, though, the 2020 Summer Olympics have become the 2021 Summer Olympics. Not in name, of course, they’re still officially the 2020 Olympics. Branding important. You wouldn’t understand.

With the future of sport hanging in the balance, I thought it’d be nice to peek back into the annals of Olympic History and explore when things were even worse.

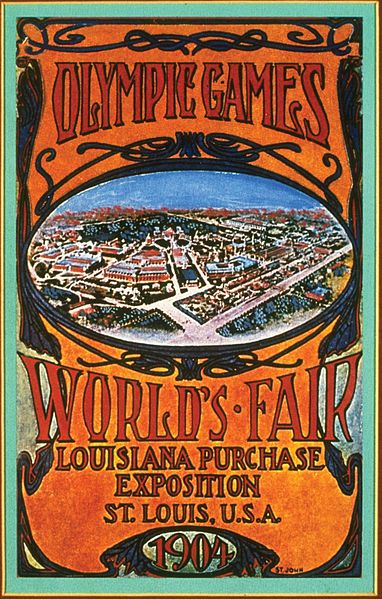

The 1904 Olympics were groundbreaking; the first Olympiad held in the United States and, indeed, the Western Hemisphere, and the third Olympic Games to have occurred in the modern era, after the Athens games of 1896 and 1900’s second Olympiad in Paris. The games took place in St. Louis, which, at first glance, is an odd choice. Placed between 1900’s Paris and 1908’s London, St. Louis looks like it’s punching above its weight.

Indeed, the games were never supposed to take place in the Gateway City. The International Olympic Committee had awarded them, instead, to Chicago. Trouble brewed, though, when St. Louis was named host of the World’s Fair that same year. Paris had held both the World’s Fair and the Olympic Games in concert in 1900, and the 1904 fair’s organizers feared two major international events held so close together would compete for the same audience. They politely asked that the games be awarded to St. Louis as well. When that didn’t work, they also threatened to hold their own, much better, anti-Olympics sporting event and compete directly with the Chicago games, but that’s a minor point. Scared out of his mind, Olympics founder Baron Pierre de Coubertin awkwardly retrieved the games from Chicago’s house and delivered them to St. Louis.

Oh shit, oh fuck please don’t make your own Olympics. Take mine!

Pierre de Coubertin, father of the modern Olympic games

The stage was set. In Saint Louis. The World’s Fair award was meant to coincide with the hundredth anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase, the event which built Saint Louis’s reputation as the Gateway to the West. It’s the starting line of the Oregon Trail (both the video game and the… trail). Prospective settlers would ride west from the city on the Mississippi, crossing the vast wilderness of the continent to what they’d hoped were better homes in the country’s newly-acquired territory. Saint Louis was on the eastern edge of Louisiana, which means it was on the western edge of not-Louisiana, far into the American interior. To make it this deep into U.S. territory from Europe, you’d have to either take a riverboat up the Mississippi from New Orleans or make landfall on the east coast and travel hundreds of miles inland.

This is in 1904, at the very beginning of mass automobile production. The Wright Brothers’ first flight was last year. For international athletes, getting to Saint Louis is going to be super hard. So they didn’t. Of the nearly 650 competitors who arrived for the games, over 500 were from the United States. Over half of the non-American athletes were Canadian. The remaining forty or so represented twelve countries. Even de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics and avowed enemy of Chicago, declined to show up for the event.

The doorstep of the wild west ended up making an appropriate setting for the 1904 games, which historian Bianca Lopez wrote “had barely any regulations and [were] mostly a complete free for all. Contestants could join at any time, even from right off the street.” Traditional olympic sports like basketball, swimming, and cycling were played alongside tug-of-war and, as Lopez writes, “something called Indian club swinging”.

But the crowning event of the 1904 Summer Olympics was the marathon, whose 24.85 miles featured wild dogs, hemorrhaging, rat poison, a car ride to the finish, and purposeful dehydration. The whole event was absolute batshit, and there’s no way I can do a better job of telling it than SBNation’s Jon Bois, whose video Rat Poison and Brandy: The 1904 St. Louis Olympic Marathon I meant to consult for this article in pieces. I accidentally rewatched the whole 21 minutes in one sitting. It’s too good.

The 1904 Olympics were so mismanaged and poorly put-together because they were an afterthought. Keep in mind, the organizers didn’t really want the Olympics so much as they wanted Chicago to not have the Olympics. How the games went didn’t really matter as long as the World’s Fair went well.

So how was the World’s Fair? Pretty neat, maybe, ignoring the racism. But it was mostly racism. The fair, known also as the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, was a chance to display to the world recent technological and cultural innovations, such as the airplane, automobile, and X-ray machine. The event’s organizers also took the liberty of using these technological innovations to prop up the idea of white supremacy. The narrative of the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition wasn’t “look at these cool things we made” as much as it was “look at all these cool things white people made”.

But showing off white innovations wasn’t enough. To solidify the message, the organizers chose to balance the superiority of white scientific invention with the inferiority of everyone else. That’s where the Anthropology Days come in.

Anthropology Days was a two-day exhibit at the fair inspired by the contemporarily-prominent ideology of Social Darwinism, which argued that political wealth and power dynamics were a result of evolutionary strength over anything else. The idea was to provide fairgoers with a side-by-side comparison of the genius of white western creation and the comparatively primitive daily lives of non-white native peoples from around the world.

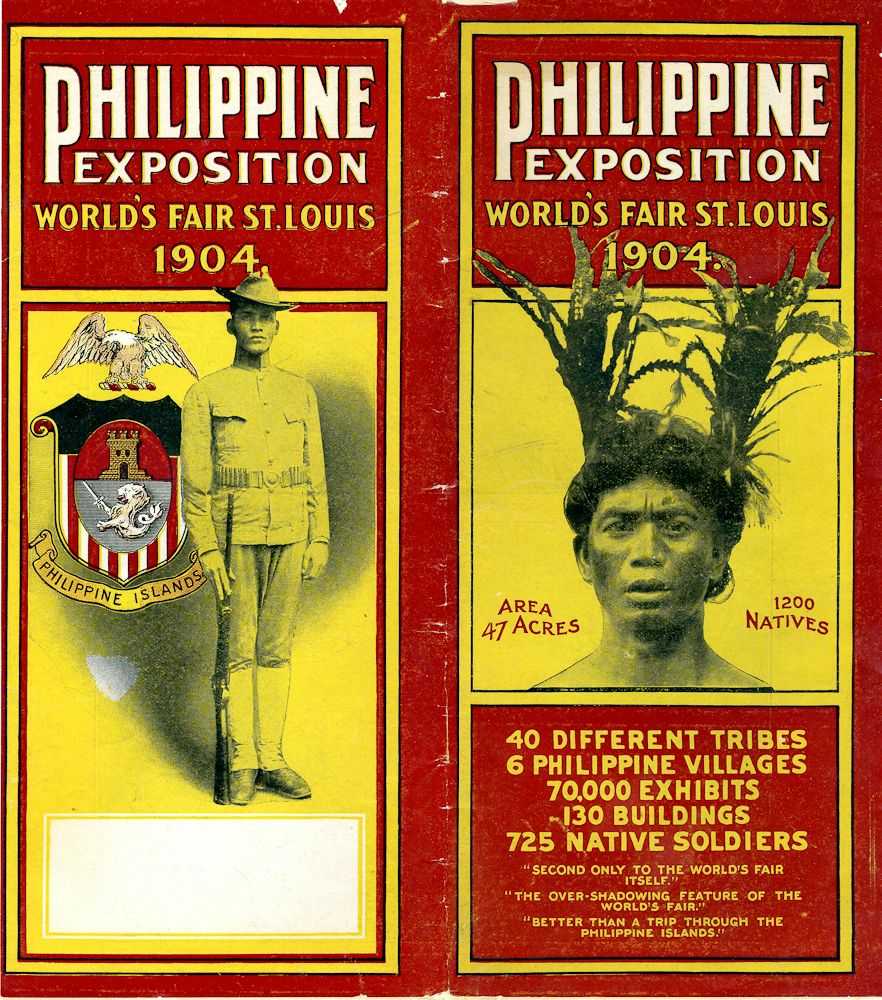

The event only lasted for two days of the months-long fair, but its scale and prominence were considerable. Mock villages were built to house African Pygmies, native Mexicans, Syrians, Turks, and a variety of other so-called savage peoples. But the crown jewel of these temporary show settlements was the Philippine Village, which took up 47 acres of land adjacent to the fair. While the other villages were meant to underscore the superiority of the white man, the Philippine village had a particularly American slant. The Philippines had become American territory just six years earlier at the end of the Spanish-American War. This wasn’t just a native village, this was a native village under the gracious protection of the United States, earned through its strength in war.

The village display may have been rough enough, but in a time where the concept of a human zoo was alive and well, anyone trying to sell tickets has to do better. So they had them compete in athletic contests, from climbing a greased pole to a mud fight. Civilized people use guns to kill each other. Silly savages. Also, make sure to get out of pole climbing on time, you don’t want to miss ethnic dancing.

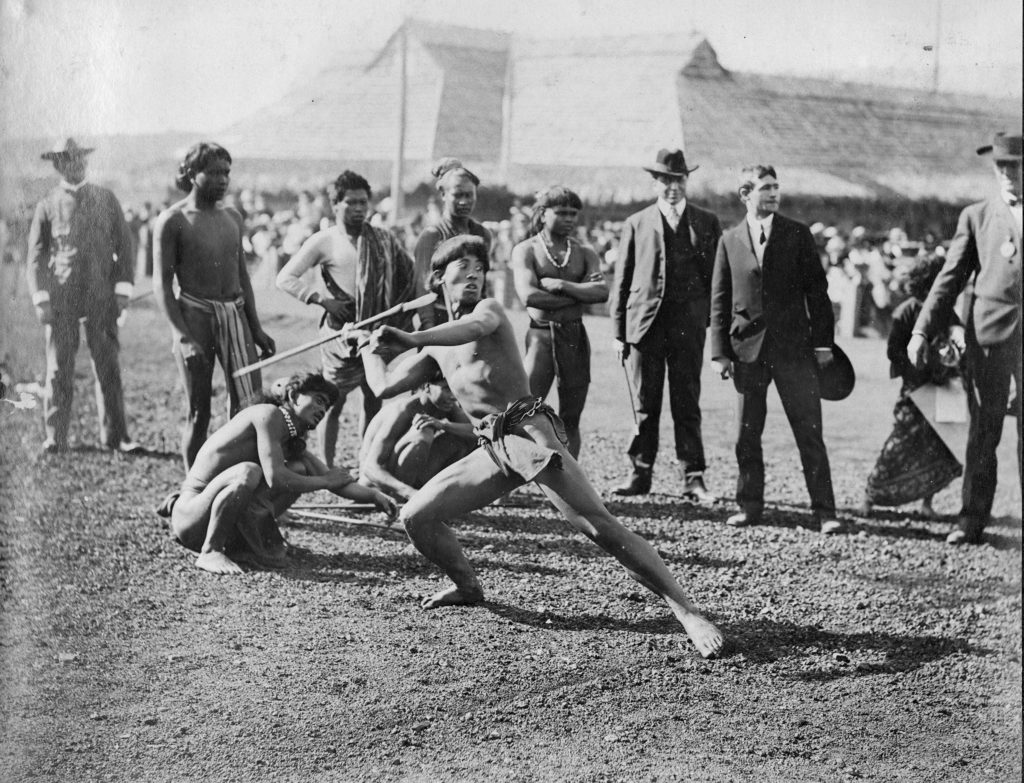

Even that could have been enough, but the job was yet to be finished. Beyond the villages and athletic displays, there were the Special Olympics. Now something entirely different, the Special Olympics of 1904 was a chance to directly contrast white athletic prowess with the bumbling savagery of the pigmented. The plan? Have white and non-white people compete at the same events, take down their performance data, and then use that data to build a definitive racial hierarchy, an absolute list of the best and worst races.

You might not expect it, but there were a couple problems with the idea of using sports to create a tier list of races. Ignoring our modern snowflake sensibilities, the first among these problems was that these events were comparing trained white athletes to amateur performers in a village show. Recruiters for Anthropology Days didn’t go hunting for race runners or javelin throwers, instead prioritizing shades of brown. Not only were the non-white competitors not trained in their sports, many had never heard of them or seen them played, and the organizers’ attempts to quickly explain the contests were less than amazing. In an article for Slate, Nate Dimeo writes that “With so many languages spoken, the starting gun concept was understandably lost on many of the participants. So, too, was the idea of breaking through the finish line: Many would stop short or run below the tape.”.

The racial hierarchy was never finished, because its contemporary architects recognized the error they had made in attempting to rank the superiority and inferiority of human beings and how silly their sports-focused methodology was. Lol just kidding. They didn’t have enough data. Bummer.

Even in their own time, Anthropology Days wasn’t considered a successful event. The whole thing was a white supremacist fever dream that came together quickly and couldn’t be properly marketed by the Department of Exploitation (that’s actually what the ad team called themselves). The event was poorly attended, and inadequate preparation made for a bad show. The day wasn’t all bad, though, providing us with definitive proof that, in a game of tennis, trained white tennis pros are better than non-white jungle-dwellers who don’t know how to play. It’s the same strategy I used to beat my Grandma in Halo. Brb, drawing up a family hierarchy.

The Olympics themselves had a few upsides. Gymnast George Eyser took home three gold medals and six medals total, despite having a wooden leg. George Poage was the first black American to win a medal, earning bronze in the 400-meter hurdles. To this day, Frank Kugler is still the only athlete to have come first in three different sports, with medals in wrestling, tug-of-war, and weightlifting. The 1904 games were also the first time gold, silver, and bronze medals were awarded to those placing first, second, and third.

So all in all, do I think it was worth it? I mean, no, obviously. But then again, I’m not really into sports. I’m not into racial hierarchies either, but those seem to come up less in conversation.

Read More

- Bizarre but True Happenings at the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis by Bianca Lopez for Washington University in St. Louis

- Olympic-Sized Racism: Remembering the 1904 games, where Indians, Pygmies, and other “savages” faced off in the interest of science. by Nate DiMeo for Slate

- St. Louis 1904 on Olympic.org

- St. Louis 1904 Olympic Games in Encyclopedia Britannica

- The 1904 Olympic Marathon May Have Been the Strangest Ever by Karen Abbot for the Smithsonian