It’s 1884 and we’re in Berlin. We’re all in Berlin, “we” being the major powers of Europe. Europe has a problem: it’s Africa. We all want it, and we’re trying to decide who gets it. We decide we all get some of it, as long as we’re there already, but there’s a problem: the middle of Africa is a dense rainforest and everyone who goes there gets malaria. Who gets that part?

Amid appeals from contestants for the prize of the Congo, the King of Belgium rises from his seat. “I will take it.” he says

“Ah!” the council exclaims. “Belgium would accept the responsibility?”

The King shakes his head. “What? No, fuck that. Fuck Belgium. I’ll take it.”

“You would be King of the Congo?”

“Yeah, that sounds cool as shit. God, I’d be such a fucking big shot, that would be so cool. Give me the Congo, I really want it now.”

Europe’s leaders met the request with unified silence before convening amongst themselves in a unanimous whisper. Finally, they lean forward and once more meet the gaze of King Leopold, now jumping in place and covered in sweat.

“We believe what you’re saying, your majesty, is that you would gracefully undertake the burden of promoting wellbeing and taking care of the people of the Congo basin?”

Still jumping, it took a tug on his shirtsleeve from his nearest neighbor to reengage the King’s focus. “What? Yeah.”

Europe’s leaders furrowed their collective brow and repeated the question; “you would be a charitable provider for the region?”

“Yeah yeah yeah, sure, sounds good. Quick question: can I have the Congo?”

Europe convened again, exchanging rapid glances at Leopold, whose eyes bore no emotion, his majesty having appeared to have descended into a hibernative state. “Well,” the continent sighed, “I don’t see any other option.” They scratched their necks, shrugged their shoulders, and turned once more to the Belgian. “Okay.” they opened, “Leopold of Belgium, we bequeath you the Congo Free State.”

The monarch pulled his fist back in victory. “Nice. Fuck yeah, that’s cool.”

The conference broke, confident that they had left the bulk of equatorial Africa in caring hands. Surprisingly, things got bad.

First, it’s worth noting that Leopold’s decision to charitably take eight percent of Africa under his wing and nurture it at his philanthropic breast was less of a spur-of-the-moment idea and more a carefully-crafted plot, the culmination of a decades-long dream to have his very own colony.

One Man’s Dream

Leopold was an envious boy. He was a king, sure, but he was the king of Belgium, which is very small and meager compared to his neighbors, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. If it’s not bad enough that those countries are big and rich and populous, they also all lay claim to far-off lands that have allowed them to become bigger and richer and more populous. Leopold didn’t have any colonies, and that was very sad. But one day, he had a brilliant idea:

“I could get a colony”, he said.

Where? Leopold wasn’t picky. He considered trying to acquire land in Egypt, leasing territory in Taiwan, acquiring Fiji, or plucking a big ol’ chunk of Argentina. In 1875, an attempt at buying the Philippines from Spain went nowhere. Then the King turned his eye to Africa.

From the start, wherever his colony was, Leopold’s ambitions came from the purest reaches of the human heart. After indulging his brain with a spicy contemporary piece lauding the benefits of forced labor in European colonies abroad, Leopold wrote that slavery was “the only way to civilize and uplift these indolent and corrupt peoples”.

“Belgium doesn’t exploit the world” he later said, “it’s a taste we have got to make her learn.”

In his valiant quest for exploitation of people thousands of miles away, Leopold’s gaze was now neatly fixed on Africa, the so-called “dark continent” (proponents of the title will have you know that that title isn’t racist, it refers to how the continent’s people are uncivilized). Already, as the first drops of sadist saliva start to spill from the king’s lips, the greater powers of Europe are ahead of him; the British, French, and Portuguese are all building substantial colonies on all sides of the continent. The coast is filling up quick, but the center is still up for grabs*.

*the center was not up for grabs. Many people lived in the center.

Leopold had decided: he was going to take the center. What was there? He didn’t know. He definitely wanted it, though. But he didn’t have a magnificent navy or coalition of trade companies to go and take it. He needed to be innovative, to act through more unconventional means. So he contracted the labor, hiring explorers to chart the territory with allegiance only to the international community and human scientific advancement. Oh, and, y’know, if a couple of lakes and rivers just happened to be named after the Belgian King, that would be fine. We’d be okay with that.

Leopold’s PR campaign had only just begun. In the coming months, he’d start setting up organizations with names like the International Association of the Congo, dedicated to the advancement of humanitarian goals along the Congo river. His organizations drew praise and members from all around Europe and North America, and soon its events were loud with conversations of the progress that could be made in Africa’s dark heart. Some association members had begun to speak about the development of the region into a modern state run by its native people. Here’s a response from one of Leopold’s representatives:

“There is no question of granting the slightest political power to negroes. That would be absurd. The white men, heads of the stations, retain all the powers”

It’s rule number one of giving to charity: first, make sure to take all the power from brown people. Then do charity.

Despite his predatory proclivity, Leopold’s campaign was working. Europe was interested in the Congo. Unfortunately for the king, Europe includes France, Britain, and Portugal. They want the Congo too, and they’re sending their guys to claim it for them.

This is a big bad moment for Leopold, who wants his neighbors to not have the Congo almost as much as he wants it for himself. He updates his strategy for the new rules of the game and sends some of his own guys to Africa with a plan: write up a bunch of contracts, hand them out to village chieftains, and get them to raise the flag of the IAC (a yellow star on a blue field. Could be worse.) No problem. Except for the chiefs. The contracts stipulate that the villages give away all their rights and sovereignty to Leopold. They can’t speak French, most are unfamiliar with the concept of literacy, and signatures are unheard of. This, of course, means the contracts are absolutely legally binding. Good job, Leopold!

450 signatures in hand, King Leopold next undertook the honorable task of hiring lobbyists to go to the United States to get congress and the President, Chester A. Arthur on board. Fat chance! Americans love liberty and democracy. They fought a war against being a colony. They’ll never support a European King using his power to subjugate people a thousand miles away. It won’t happen.

News bulletin: It happened.

To be fair, it was a series of very convincing arguments that led the U.S. Congress to formally recognize Leopold’s claim on the Congo. Leopold said that American businesses would be able to operate freely, and Senator John Tyler Morgan of Alabama says we can send all the black people there. In 1884, the United States becomes the first country to recognize the Congo as the personal property of Leopold II.

Later that year, with Europe abuzz at the idea of colonizing and “developing” (😉😉) Africa, Berlin holds a conference. All the European big-wigs get together to make decisions about who gets what. Contrary to popular belief, the conference doesn’t explicitly draw out a map for how the continent should be shaped, but instead serves as an opportunity for leaders and diplomats to come to agreements on disputed claims. Leopold doesn’t actually show up. He doesn’t need to. By the time the conference convenes, he’s already won the Congo through a series of deals with France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, bolstered by the American recognition we talked about in chapter this one.

The Congo belongs to Leopold.

The Congo’s Nightmare

It’s here that the story of the Congo changes tone pretty rapidly. It’s hard to talk about Leopold’s reign over the Congo Free State as he calls it with the same candor and carelessness I’ve attributed to his zany journey to make it his in the first place. Leopold’s deep desire for a colony is easy to make fun of. It’s dumb. His administration of the colony itself, though, isn’t so easily lampooned, at least not in the same way.

Recording the atrocities committed in Leopold’s Congo isn’t comparable to telling a story; it’s more of a long list, with each entry overlapping the last. Leopold’s promise to Europe when he took on the burden of ruling 7% of Africa was to provide for its humanitarian development and to act charitably. It’s almost impossible to locate evidence of any attempt to follow through on that promise anywhere in the country. Leading up to the 1884 Berlin conference, the German government of Kaiser Wilhelm II agreed to recognize Leopold’s claim. Later, Wilhelm himself would label the Belgian King “Satan and Mammon in one person”.

On a relief mission, Leopold’s chief explorer kidnapped women and children, using them as bargaining chips to trade for food. One expedition member had the severed head of a native shipped to Europe and taxidermied. Early on, the Belgian and European colonists popularized the use of a hippopotamus-hide whip called the chicotte, which would become the fashionable tool of punishment in the colony for the next ninety years. White criminals were not put at the mercy of chicotte-wielding officials. Black criminals and those who did not work hard enough almost always were.

The atrocities ramped up from there. Natives were forced to provide sustenance and goods to the colonists without compensation; if they refused, their homes would be burned to the ground. Traders started kidnapping African women to use as concubines. Officers started shooting natives as punishment, to intimidate, and for sport.

In convincing Europe to give him the Congo, one of Leopold’s appeals focused on the evils of slavery. Not European slavery, of course, but Arab slavery. His forces on the continent would do away with the practice for good. To that end, he was moderately successful in that he largely kept Arab slavery from the Congo basin by instead introducing Belgian slavery. Able-bodied laborers were captured, bought, and sold, starting some twenty years after the end of the American Civil War.

Toward the end of the century, Leopold brought on a prominent slave dealer from Zanzibar to act as governor of the Eastern part of the colony. He offered to buy the freedom of all of the dealer’s slaves with the condition that they offer him seven years’ labor in return.

Natives were regularly punished with the whip for the misdemeanors of their neighbors. The colonists subcontracted these lashings by conscripting native Africans to whip other native Africans. The practice of kidnapping women and children was developed further, and became a way to coerce men into fulfilling hard labor requirements. As the demand for control and punishment grew, the government began constructing “children’s colonies” to resupply its growing army with child soldiers.

Until now, the main economic export of the Congo valley is ivory. It’s worth a lot. Soon, though, a technologically-advancing Europe will be in need of rubber. India and Brazil are struggling to produce. It turns out there’s a lot in the Congo.

The situation in the Congo is bad. It’s about to get a lot worse.

The insane value of rubber in a rapidly-industrializing world imbues the colony’s traders and officials with an avaricious zeal. Rubber harvesting is rapidly made mandatory for most of the colony’s natives. The administration introduces rubber quotas, the meeting of which requires labor amounting to a full day’s work. The fields go fallow, the villages go quiet. As natives struggle to keep up, the campaign of hostage-taking accelerates; women are kept captive until men can collect enough rubber to buy their freedom.

Desperate to provide the rubber required of them, some Congolese laborers start to mix the rubber in their buckets with pebbles to add to the weight. One officer catches on and forces those caught to eat the mixture. Initially, Africans are paid paltry trinkets for their collections; beads, tools, eventually the colony’s administrators land on brass rods. Payment in currency is forbidden by statute. Eventually, most aren’t being paid at all.

Razing villages completely becomes a common punishment for those who fail to meet rubber production quotas. Natives take to the forest to hide when the army shows up. One man arrives to a trading post with fifty buckets of rubber. One of the buckets isn’t full enough. The official on duty shoots him dead. Killing for sport becomes more common. Punishment of white colonists is near unheard of.

Throughout the reign of terror led by colony officials, officers struggle with the economics of mass murder in a way not properly replicated until the Holocaust: killing this many people costs a lot of money, and that money adds up. Bullets aren’t cheap, the Congo’s administrators reason, and something has to be done to ensure they’re being used effectively. The macabre answer to their question comes with the adoption of a new policy: proof of death by way of human hands. To replace fired bullets with new ones, soldiers must present officers with the right hand of the person the bullet was used to kill.

This grotesque policy of enforced corpse-maiming starts awful and gets worse fast: throughout the colony, soldiers begin severing the hands of living natives for economic reward. They turn to bludgeoning their victims as a technique to conserve ammunition. Years later, photos of mutilated natives, their hands violently stolen from them for petty greed, would be some of the most convincing evidence against Leopold’s administration.

One Congolese song quoted in King Leopold’s Ghost ends “We shall make war… we know that we shall die, but we want to die. We want to die.”

All the King’s Newsmen

Meanwhile, Leopold is unsatisfied; not by the tragedies occurring daily in his colony, but by his lack of expansion and his failure to acquire another one. He involves himself in schemes to steal parts of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, he attempts to buy Uganda using some weird, contrived claim that the territory changing hands will allow him to prevent the ongoing Armenian genocide. He wants part of China.

Eventually, the actions of missionaries, journalists, and diplomats, coupled with the brave testimony of local Africans, allows word of the atrocities of the Congo to leak out and into the American and European press. The process is slow by nature, but slowed further by Leopold’s shrewd talent for strategy.

The King embarks on a media campaign, maybe the first of its kind. He sends his agents on whataboutist campaigns against the British, arguing his atrocities can’t be that bad if they’re also happening elsewhere. He holds North Korea-esque guided tours where journalists and tourists are led on carefully-shepherded expeditions along the river. He pays off an American senator and hires a San Francisco lawyer to lobby another. Eventually, he’s paying out tremendous dividends to news outlets throughout Europe and America to either keep the story quiet or to push his own version of events.

The back-and-forth continues for a disgustingly long time, but eventually Leopold agrees to conduct a trial of his administration’s practices in the Congo. Naturally, that trial is presided over by a panel of three judges hand-selected by the King. This will be fun and unbiased.

The anti-Congo campaign, staffed by a truly impressive array of people I don’t have time to introduce here, puts together a prosecution anyway, sourcing testimony from many of the missionaries, journalists, and natives who originally made their voices heard. Their statements and stories evoke strong emotional response in the courtroom. One tribal chief uses 110 twigs to visualize the men, women, and children of his village killed by Leopold’s forces. The commission writes a surprisingly-scathing report. The colony’s governor-general, having read it, commits suicide. The commission prepares to distribute the results to the world. And then… nothing.

Leopold beats them to the punch. The report is long, and journalists working on a schedule don’t want to read it. Before it can be officially published, the King’s team publishes a significantly shorter “official summary” of the report. The media picks that up instead.

Eventually, though, the news becomes overwhelming. The anti-Leopold coalition grows further, attracting such faces as G. Stanley Hall (first president of the American Psychological Association), Booker T. Washington, and Mark Twain. Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle joins later. John Tyler Morgan, the rabid “back to Africa” senator from Alabama is convinced to reverse course: if Leopold’s Congo is so harsh, how will he ever convince all the black people to go there?

Leopold knows his reign is over, but in one final magic trick, he puts Belgium in a bind; the country believes that its best recourse is to accept the task of governing the colony itself. To that end, its government agrees to pay Leopold hundreds of millions in dept forgiveness and direct payment, including 50 million francs as a “gratitude” payment for his careful administration of the Congo.

By the end of the King’s reign, the population of the Congo is estimated to have fallen by ten million people, or fifty percent.

One King to Another

In the colony’s years under Belgian administration, improvement was marginal. Resource collection wasn’t required directly, but a head tax imposed on all citizens required them to generate economic development somehow. The chicotte whip remained in active use, and chiefs were still paid to provide slave laborers to the state. Rubber booms again during World War II, and the Congo remains its largest single source.

In 1960, amid a wave of independence movements throughout the continent, Belgium formally renounces its governance of the Congo. When its democratically-elected leader, Patrice Mumbumba, is seen as getting too close to Soviet socialist ideals, the United States and Belgium work together to assassinate, dismember, and dispose of him. The United States soon thereafter announces its support for the country’s new dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, who amasses a tremendous personal wealth through his stakes in the country’s monopolous corporations and direct payment by the United States.

Of Mobutu, the New York Times writes “his systematic looting of the national treasury and major industries gave birth to the term ‘kleptocracy’ to describe a reign of official corruption that reputedly made him one of the world’s wealthiest heads of state”. Sese Seko was overthrown after a 31+ year reign by militant leader Laurent-Desire Kabila, who was assassinated four years later and replaced by his son, Joseph. Joseph Kabila remained President of the Congo for eighteen years before agreeing to step down and transfer power democratically. That transfer occurred on January 24, 2019.

Leopold II, King of Belgium

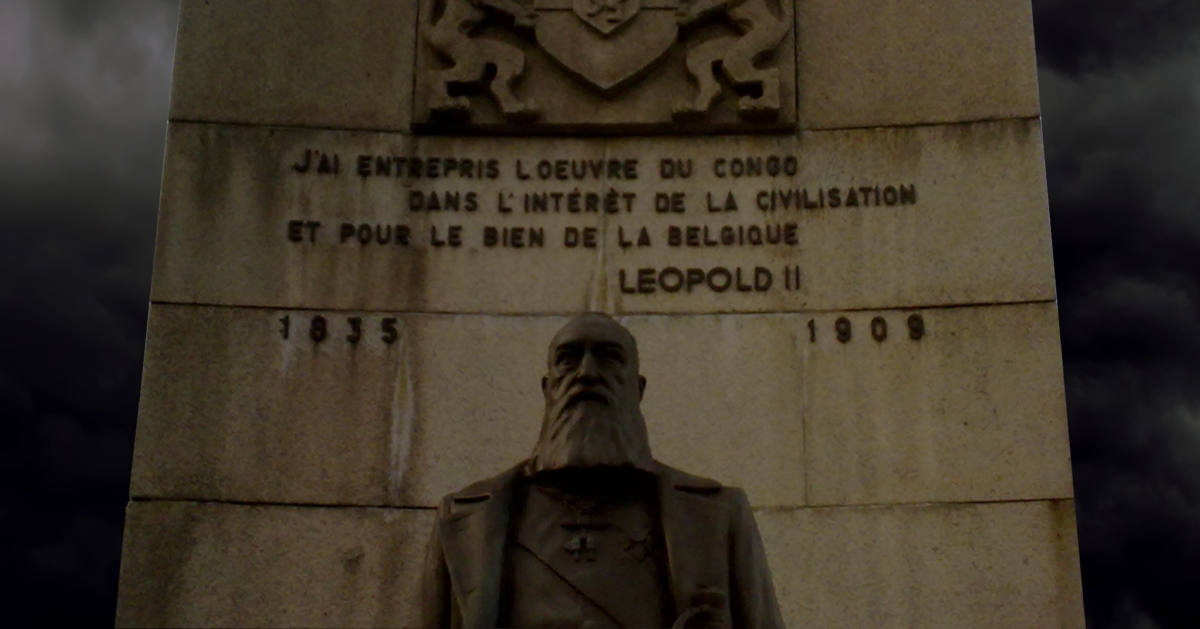

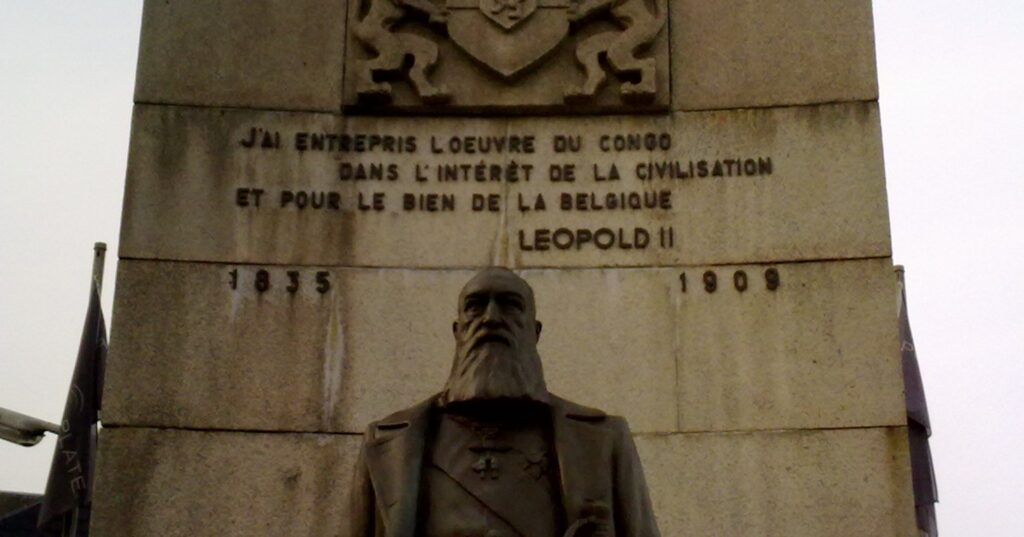

The Belgian King died in 1909, leaving much of his wealth to his surviving mistress and tying the rest of it up in convoluted corporations established in the countries that neighbored his own. Leopold II presided over his native country for 44 years. He lived lavishly and elegantly, spending much of his time upgrading his palaces in and around Brussels, buying property abroad (especially on the French riviera) and avoiding his wife and daughters. During his life and after his death, statues depicting the King were erected throughout the Belgian state. As a century passed, the statues would remain as the common memory of the nation’s involvement in the Congo swiftly evaporated.

Public knowledge of Leopold’s atrocities in Belgium is not common. At least, it wasn’t. In 2020, the murder of George Floyd by American police officers in Minneapolis sparked a wildfire of protests around the world, spreading initially to other major cities in North America before being swept across the Atlantic into Europe, where Belgian human rights groups joined the call for equal rights and recognition of their historical suffering.

Statues of the Congo’s sovereign, the Belgian King, were defaced and destroyed throughout the country, covered in paint and marked with phrases of sharp rebuke. Since the initial protests, several of these statues have been removed, but some still stand. According to the BBC, the current King of Belgium’s younger brother, Prince Laurent, spoke in defense of Leopold following the 2020 protests, arguing that Leopold II could not be held personally responsible for the atrocities committed in his name “because he never went to the Congo”. Out of sight, out of mind.

Internal response to and recognition of the state’s history of atrocities remains limited and mixed. The New York Times reported that Belgium “apologized for the kidnapping, segregation, deportation, and forced adoption of thousands of children born to biracial couples during its colonial rule of Burundi, Congo, and Rwanda.” This was the first time Belgium formally accepted responsibility for the crimes of their sovereign and the Belgian state.

Leopold died well over one hundred years ago. His life and reign are well-entombed in the set stones of history. But, since his departure, the Congo has seen only a handful of leaders, whose appointments and respective periods of rule follow a clear thread back to the once so-called benefactor of the Congo valley. Similarly, Belgium has seen only a handful of Kings, familial successors to that same storied sovereign. Baudouin I, whose reign marked the relinquishing of the Congo to its native people for the first time in nearly a century, died in 1993.

For some in the Congo, the wound is still fresh. For many, it is not yet closed, the country’s bloody history of dictatorships, corruption, and near-constant war a sort of inheritance from Leopold and Belgium, who spent 80 years involved in advanced economic extraction and virtually none in statecraft. In 1960, the Congolese were expected to figure democracy out for themselves. When they did, the Belgians and Americans quickly intervened.

The Congo bears the scars of yesterday. So too does a Belgium that for a century revered a brutal and tyrannical king, even if those scars are much less deep and far less plentiful.

History doesn’t end with the deaths of its participants. It’s inherited by their successors. It’s to us to learn from the examples of those who preceded us. In the case of Leopold and the Congo, there is much to learn. Perhaps we should learn, for example, that mass murder is not an acceptable tool in the quest for ivory and rubber, or that colonial rule necessarily lends itself to dehumanization and brutality. Maybe the greatest lesson we can learn from Leopold, though, is that ambition is not a virtue in and of itself; it is not enough to want greatness, to desire power, or to plea the benefit of potential charity. Leopold dreamed a great dream, and Europe (and much of the western world) took him at his word long after it had turned to nightmare. The lesson of Leopold cannot be isolated to Leopold; the important message is not that a bad man used great power to commit evil acts, but instead that such a man was allowed that power to begin with. Leopold did not have the Congo thrust upon him, he chose it. He wanted it. He was allowed to take it. And he destroyed it. Leopold alone dreamt up the Congo Free State. The world helped him build it.

Read More

- King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild*

- Leopold II: Belgium ‘wakes up’ to its bloody colonial past by Georgina Rannard for BBC News

- Statue of Leopold II, Belgian King Who Brutalized Congo, Is Removed in Antwerp by Monika Pronczuk and Mihir Zaveri for the New York Times

- The real history of Belgium’s King Leopold II by Anne Wetsi Mpoma for Deutsche Welle

*By far the primary source for this piece.

Image

- Monument à Léopold II by Olnnu for Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0), adapted with Dark Clouds Storm Thunderstorm by Jahoo Clouseau on Pexels; this work is published through the Creative Commons Share Alike 3.0 license. What’s mine is yours.

- Story of the Congo Free State, unknown author (public domain)

- Castle of Laeken, Belgium by Athenchen, cropped, published through Creative Commons Share Alike 3.0 license