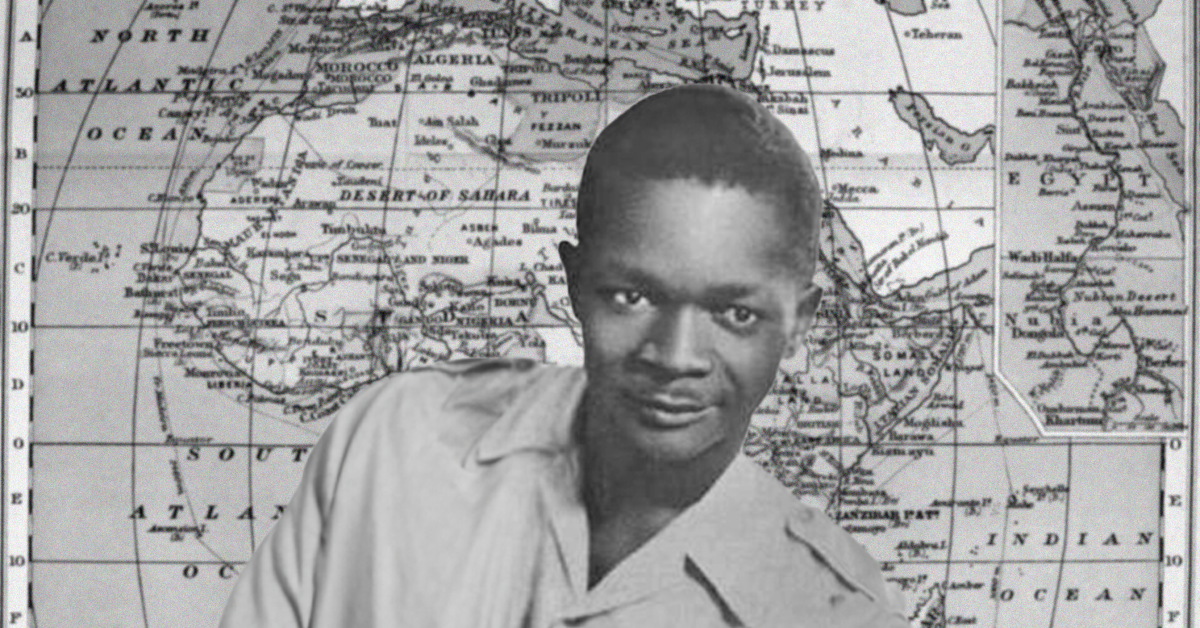

Jean-Bédel Bokassa was not a politician by trade. A blood relative of his country’s first president, David Dacko, Bokassa’s rise to power was far from preordained. His own father was a rebel who had been inspired by Karnu, the Centrafricain spiritual leader and part-time wizard who inadvertently led a trans-territorial uprising against French rule in Africa. For his transgressions against the French administration, Bokassa’s father was beaten to death. His mother, destroyed by grief, took her own life shortly thereafter.

Bokassa was left an orphan and taken in by an order of Catholic priests. It was under their supervision that he adopted the double-barrelled name by which he would be known for decades to come. Each of the two constituent names bore meaning to the young Bokassa; the first, Jean, was the name the Priests had given him, taken from Saint John the Baptist, a Christian prophet and one of that faith’s premier saints. The second name, Bédel, was borrowed from the just-as-important author of a grammar textbook Bokassa liked.

On the heels of World War II, Bokassa joined the French army, fighting for the conglomeration of French African territories that threw their strength behind General Charles de Gaulle after the surrender and collapse of the government in Paris. It was fighting under de Gaulle, the father of the French Fifth Republic, that Bokassa first nurtured a life-long obsession with the man.

After the war, Bokassa transferred to French Indochina, today’s Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam (or, if you don’t care enough to learn the names of three countries with rich and unique histories, India-China). There, he met a 17-year-old, started a family with her, and summarily abandoned them all in 1953, just in time to avoid the bubbling conflict that would become the Vietnam War.

He went next to France, the imperial homeland where he spent his time teaching African soldiers how to operate radios. Far away from combat but still fancying himself a predator, Bokassa took an interest in a 13-year-old schoolgirl he happened to see on the street. He followed her home (as you do) and approached her family, seeking the girl’s hand in marriage. Her father received Bokassa, but given that he is decades older than the girl, ultimately rejects the proposal. That he’s also a distant relative didn’t factor into it. Of course, even the age thing didn’t really make that much of a difference, as the girl’s father relented just a few years later and the two had their dream wedding. At the time of the marriage, the Bokassa’s bride was 16. He was 44.

Hot on the heels of his totally cool child marriage, Bokassa returned to the now-independent Central African Republic and enrolled in its military. In France, Bokassa had been a Captain, a mid-range officer. In Central Africa, he was immediately assigned the rank of Battalion Commandant, in part attributable to his experience abroad and in part thanks to his kin connections to both President Dacko and the father of the nation, Barthélemy Boganda.

Despite the prestige of both rank and assignment (his first job was building the country’s army from the ground up), Bokassa was considered a lower-ranking member of Dacko’s cabinet. This explained the fury felt by the President’s Chief of Protocol when Bokassa somehow always managed to squeeze himself closer to Dacko during meetings and photo ops.

The Chief of Staff was among a group of citizens and government officials that had begun to bristle at the growing power of the military and ballooning influence of Commandant Bokassa. Still, Dacko downplayed his cousin’s capabilities, joking at a dinner “Colonel Bokassa only wants to collect medals and is too stupid to pull off a coup d’etat.” Check and see if we come back to that idea later.

Beneath his brasher exterior, Dacko must have had concerns. Bokassa left the country with an official delegation to Paris in 1965. After completing their itinerary, the rest of the delegation returned from France without issue. Bokassa alone was forbidden from boarding the plane and left alone in France, thousands of miles away from the country where he was a cabinet officer.

Dacko eventually relented and welcomed his cousin back to the capital city of Bangui. No one knows for sure what caused the change of heart, except, of course, for Bokassa, who claims it was the personal interference of his hero, French President Charles de Gaulle who demanded his “companion in arms” be allowed to return home.

Back in Africa, Bokassa had a bone to pick with his cousin-President. It wasn’t the obvious, that whole “you exiled me from my home” thing; that was water under the bridge to the man responsible for the Centrafricain Army. What Bokassa really wanted was a pay raise. When Dacko refused the request, the man too stupid to pull off a coup d’etat decided to smarten up.

Despite his unmatched level of control over the country’s military, Bokassa’s road to coupdom was far from secure. The Centrafricain Army was new, and the forces it did have were stretched thin combating Congolese rebels in the south and Sudanese militia in the north. Bokassa also worried that the men who followed his orders in battle against outsiders would cast him aside when commanded to lay siege to their own government.

Perhaps the most pressing of Bokassa’s concerns was the creation of the national gendarmerie. President Dacko’s public disbelief in his cousin’s ability to challenge his rule was betrayed by his private formulation of this new, second military force commanded by a Dacko ally, Jean Izamo.

Dacko quickly enrolled a number of soldiers comparable to the number making up the ranks of Bokassa’s existing armed forces in the new gendarmerie to hedge the growing power of his cousin. But just as the President was forging a military alliance with Izamo, Bokassa was establishing a profitable relationship of his own to the north.

Birds of a feather

Alexandre Banza’s background echoed Bokassa’s. He began his career as a soldier in the French Army, serving in the First Indochina War before his service took him on a tour of military stations throughout French Africa. By the time he’d been freed of his military obligations, new opportunities had opened up in his home country as the President and his allies struggled to build a military from the ground up.

Bokassa and Banza were natural allies. Their similar backgrounds aside, each man had something the other wanted: Banza was a field commander with a closer relationship to the men on the ground than the power-jockeying Bokassa, and Bokassa was a natural recipient of the power and prestige desired by the outsider Banza. The two cemented their bond by planning the upcoming revolution, the military coup necessitated by Dacko’s refusal to give his cousin’s salary a cost-of-living adjustment.

This, as we’ve established, was a slight Bokassa couldn’t stomach. He was team coup all the way. But even with his insurgent ego, he had his doubts. In the end, his friendship with Banza paid off, with the subordinate officer pushing his commander to go through with their plan. It’s always nice to have an accountability partner.

Phase one was readying the military. With Bokassa and Banza in command, that was easy enough. Phase two was getting the gendarmerie out of the way. In service of this goal, the two hatched a plan to use New Year’s Eve celebrations and end-of-year necessities as cover. As the armed forces approached the capital, Bokassa phoned his rival, Jean Izamo, to report that the two had forgotten to square some documents away that needed reviewing by the end of the year. He assured Izamo that the process required only a few signatures and that he’d be on his way soon. I hope you don’t mind if I shock you here: Bokassa lied.

Once he’d arrived, Izamo was immediately taken into custody. Bokassa and his allies were now free to move into the capital, which they did without significant resistance. When they breached the Presidential Palace, they were surprised to find Dacko absent. It turned out he’d left on an unrelated trip to the countryside, but Bokassa was rattled all the same.

Inside the country’s highest house of power, Bokassa wasted no time. He named himself commander-in-chief and immediately exerted the power afforded by that role to order Ngaragba Prison, the country’s largest, emptied. This was the first mass-release of prisoners Bokassa had ordered, but it wouldn’t be his last; spasms of clemency would become a hallmark of his rule, a personality quirk he maintained until the very end. Second to clemency among Bokassa’s varied interests was the new imprisonment of his political opponents. Shortly after he’d had Ngaragba emptied, he’d wasted no time in replacing its former occupants with new ones.

The first man Bokassa had taken into custody, Jean Izamo, would not share the fate of his allies in Ngaragba. He and the chief of Dacko’s presidential guard were subject to mistreatment and torture before their eventual deaths at the hands of Bokassa’s men, two of ten or so recorded casualties of the mostly bloodless coup. Another of those ten was a night watchman killed defending a radio station with a bow and arrow.

The new order

As the first sunrise of the new year cast its rays on Bangui, international condemnation fell swiftly upon Bokassa and his troops. The new commander-in-chief attempted to ingratiate himself with the global community by blaming his actions on a made-up alternate coup he argued was being organized by the gendarmerie and their Chinese allies. To cement the claim, Bokassa promptly severed contact with China, a country that had recently endowed his predecessor’s government with an interest-free loan of 1 million CFA francs.

The usurper’s story about fighting a ghost coup with a real one wasn’t convincing, but the international condemnation proved toothless, especially when the republic’s most important ally and trading partner, France, relented after Bokassa threatened to leave the African monetary union, a component to the enduring French economic stranglehold over its former colonies. Without significant opposition inside or outside the borders of the Central African Republic, Bokassa got to call himself President. He even got to meet his hero, French President Charles de Gaulle.

Next time: The President

Image

- Bokassa_1939 from the Wikimedia Commons

- This one’s public domain, I can do whatever I want with it.

Read More

- Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa by Brian Titley