There are no boundaries on Earth like the Himalayas. Stretching 1,500 miles from the Pakistan-Afghanistan border in the west to where India and China meet Myanmar in the East, these mountains act as a bulwark forcing apart two of the largest and most populous countries in the world. Mount Aconcagua in Argentina is the tallest mountain outside of Asia, standing at some 23,000 feet above sea level. Travel the length of the Himalayas and you’ll find one hundred mountains taller than that.

This chain of cloud-rending spires forms a nearly-uninhabitable extreme at the far edge of Earth’s terrestrial projections; on one side, the Tibetan plateau boasts a population of somewhere around four million people twice as far from sea level as the city of Denver. At that high (over 11,000 feet), you’re taking in around 33% fewer oxygen molecules per breath. That difference in air and pressure can lead to significant altitude sickness for travelers if they don’t take the time to acclimate. Tibet on its own is an extreme so far beyond the realm of normal human habitation that it’s been hypothesized that the first people to settle there had developed a genetic adaptation that made them better suited to a low-oxygen environment.

Meanwhile, to the south, the Himalayas soar twice as high as Tibet. If you took a cross-section of the stretch of Earth between sea level and Denver and stacked it on top of itself five times, residents of the new five-mile-high City would still be thousands of feet below the peak of Mount Everest.

And somehow, there are people here, people whose ancestors didn’t simply look at this monument to the gods puncturing the heavens before them and think “fuck that.” People who put our parents’ stories of walking to school uphill in heavy snow to shame. Their cultures are rich and ancient, protected from the outside by the greatest bulwark on the face of this planet. Boats conquered the Pacific. Human engineering cut paths through deserts and jungles. But even airplanes avoid the Himalayan mountains.

The last time I wrote about the Himalayas, the topic was Bhutan, a country nestled comfortably in the mountain range’s southeastern valleys. Its capital, Thimphu, is over 7,000 feet up. Its flag is one of my all-time favorites: half-orange and half-yellow, bisected diagonally. And straddling that separating line, much as Bhutan straddles the mighty Himalayas, is an ornate white dragon. Bhutan is known to its people as “Druk Yul”, or Land of the Thunder Dragon. Its leader is a hereditary monarch known as the Dragon King.

The current Dragon King, Jigme Wangchuck, has a story that feels purpose-written for a Disney princess film. He ascended to the throne at 28 following his father’s abdication. He married a commoner, introduced democratic reforms to the country, and embarked on a celebratory tour of Asia where locals in Thailand called him “Prince Charming”. (He’s very hot).

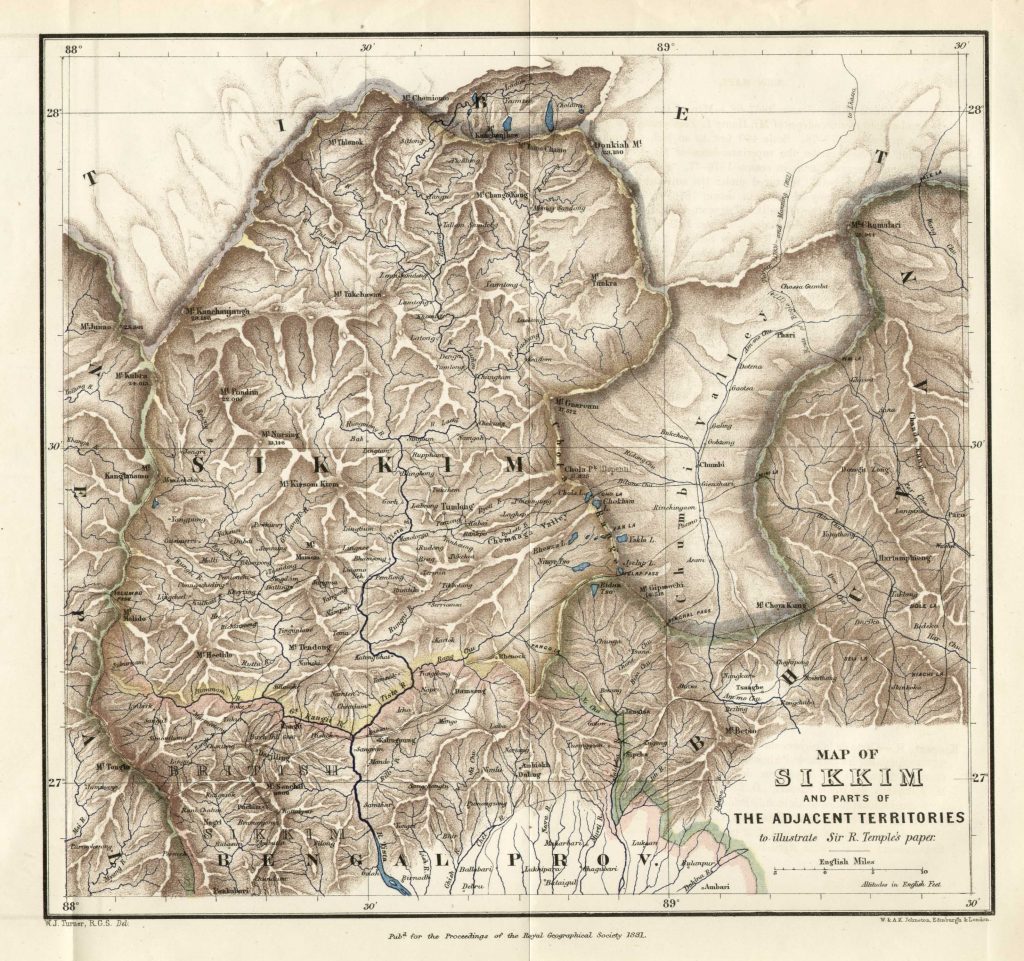

With an average elevation of 10,761 feet, Bhutan is the highest country in the world, beset on all sides by the world’s two most populous countries, China and India. It doesn’t endure that pressure alone. The second-highest country, Nepal, is also sandwiched between the two Asian colossi. Despite all they share, Bhutan and Nepal don’t border one another. They’re separated by a relatively tiny wedge of land 40 miles wide. This is Sikkim, the lost kingdom of the Himalayas. At its metaphorical height, Sikkim was an independent nation with a king known locally as the Chogyal. But while its neighbor and cultural cousin Bhutan’s king was praised and lauded from the earliest days of his reign, the Chogyal of Sikkim suffered a far different fate, one that would force him witness the dissolution of his country and everything he held dear.

This is the story of the last Chogyal of Sikkim.

The Hidden Valley

While it lived, Sikkim was a small country about the size of Delaware, which itself is a state that, if not for Joe Biden and limited liability companies, you wouldn’t know exists. Today, the land that once made up the kingdom boasts a population of 610,000, putting it somewhere between Wyoming and North Dakota, the latter a state I can’t compare it to because I don’t know anything about it. (It has Fargo the city but not Fargo the movie, and that’s enough for me.)

Sikkim doesn’t have a Dragon King, but its state animal is the red panda (scientifically the best animal), and its official bird is the blood pheasant, which sounds like it should be endemic to a Souls game and not a Buddhist country in the Himalayas.

What the country’s monarchy lacks in dragon references it comes close to making up for in longevity: its final Chogyal was a direct descendant of its first, Phuntsog Namgyal, who took power in 1642.

Namgyal’s kingdom was populated primarily by two major ethnic groups: the Lepchas, some of the first people to set foot in the mountainous region, and the Chogyal’s own people, the Bhutia, who escaped to Sikkim not long before his coronation in an effort to escape war in their native Tibet. These are the First Men and the Andals of our story. Or, if you’re less nerdy, the Britons and the Anglo-Saxons. If you’re less nerdy still, I guess you can call them by their names.

Sikkim retained its full independence for a couple of centuries until it was rudely disrupted by a well-known trespassing creep known as the British Empire. Like any good drug dealer, the British started things off with good times (returning land that the adjacent Nepalese Kingdom had taken from Sikkim in exchange for Sikkimese military support) before developing a more complete reputation as a back-alley bad time trader, first by convincing the reigning Chogyal to sign over Darjeeling, one of Sikkim’s largest cities. The Chogyal saw this as the path to regaining more territory lost to Nepal, appeasing the British here for more benefits over there. The British just wanted a place to put diseased people. They’ll later go full mea culpa and admit Sikkim was fucked over, but they’ll also admit that they like Darjeeling too much to give it back. This is not the last time the Sikkimese will have to attend one of the world’s worst apology parties.

The British establish a protectorate over Sikkim in their (mondo successful) quest to dominate the entirety of the Indian subcontinent. Once in power, they get to work on a passion project: shooting the country in its knees at every opportunity. Early on, before they even have a measure of control over the small kingdom, the British use it as a chip in bargaining with the Chinese Empire; they’ll agree to recognize Chinese hegemony over Tibet if China acknowledges British authority in Sikkim. Fans of history are getting indigestion: the British are planting seeds the Chinese will reap in a century.

In the decades following their Himalayan debut, the British begin sculpting the country to their colonial specifications. It’s a big undertaking for which they’ll need a lot of labor; more than Sikkim can provide. So they go next door to Nepal and start shipping Nepalese laborers to Sikkim to supplement their operations there. It’s not the last time the British will use the Nepalese to fight their battles abroad. It’s also not the last time they’ll bring workers across the Nepal-Sikkim border. They keep ferrying more and more until the population of Sikkim, once primarily native Lepcha and Tibetan Bhutia, is 75% Nepalese. This population shift has potential to massively affect the future of Sikkim. (If you’re one of the few readers who didn’t hate my Game of Thrones analogy three paragraphs ago, you’ll appreciate knowing that we’ve met our Rhoynar. For fans of history who don’t give much of a shit about accuracy, we can call them the Normans.) The British, who see the Nepalese migrant laborers primarily as conduits to manifest their Lego kingdom, don’t really care.

Luckily(ish), British rule over Sikkim, and South Asia as a whole, doesn’t last forever. In the late 1940s, the tides of independence finally turn in the subcontinent’s favor. One giant is vanquished, but to the south, another is just beginning to stir.

The New Boss

Before they got out of dodge, the British had a pretty ironclad strategy for governing hundreds of millions of people a world away from London. Rather than replicating the North American model (“this shit’s mine now, fuck off”), the Brits enlisted local leaders to govern their newfound territory for them. If a local Prince didn’t want to give up his land to the Lord of the Waves, a competing Prince with a suspiciously-timed shipment of British guns would be happy to.

When they found it in their hearts to depart their favorite diamond mine of a country, the British handed most of the territory over to the nascent Republic of India, whose government didn’t take too kindly to the collection of princes who still ran somewhere around 40% of the country’s land. The Instrument of Accession, a legal document that came into effect in 1947, outlined a process by which each of these princely states would be expected to join one of two new Indian nations, the majority-Hindu India or the primarily-Muslim Pakistan.

For the most part, the process of accession was fairly straightforward and without significant protest; princes in both India and Pakistan agreed to give up their titles and land for limited salaries and benefits that ended in India by 1956 and in Pakistan by 1969.

Of course, things couldn’t be that easy for everyone. Some principalities, like the Indian State of Hyderabad, put up more of a fight, in that case leading to an Indian intervention and invasion in 1948. Another conflict with a longer tail began on the northern edge of the subcontinent when the majority-Muslim principality of Jammu and Kashmir was similarly invaded by Pakistan. Reacting to the invasion, the state’s ruler petitioned to join India, giving both nations pressable claims over the mountainous region and setting the stage for a conflict that remains unresolved today.

But even as India and Pakistan demonstrated efficiency in digesting and incorporating territories that had previously been subservient only to the British Empire, some of the subcontinent’s states remained uncomfortably beyond their grasp. The two most prominent of these, both then and today, were Nepal and Bhutan.

Nepal joined the United Nations in 1955, elevating its status to one of equal weight with the rest of the world’s sovereign nations. Bhutanese membership in the UN didn’t come until 1971, and before then, the country maintained an agreement with India whereby India would extend protection to the small Himalayan Kingdom and the two would cooperate on matters of foreign affairs.

The would-be Chogyal of Sikkim (then going by the title Maharajkumar), Palden Thondup Namgyal, negotiated a similar treaty with India in 1950. The two treaties came with at least one key difference: while Bhutan had managed to secure for itself the status of a protected state, one whose foreign affairs were managed in tandem with India, the Maharajkumar’s treaty made Sikkim a protectorate, meaning its own foreign relations were made the permanent responsibility of the Indian government in New Delhi.

This difference, small in text, would become a headache plaguing Sikkim for the next two and a half decades. But at the time, for the future Chogyal, it was a major victory.

The Twelfth Chogyal of Sikkim

Palden Thondup Namgyal wasn’t supposed to be Chogyal. He was the second-born son of Chogyal Tashi Namgyal, himself the younger brother of a short-lived Chogyal who took power when his brother took an extended vacation to Tibet and refused to return. That sounds like a euphemism for death, but he really just liked it better in Tibet.

Thondup’s father Tashi technically ruled from 1914 to 1963. An eccentric maybe by western standards, the only picture on his Wikipedia article is one of the Chogyal looking like a Himalayan Morpheus sat across a table held up by little skeletons from a member of the German Nazi Party. I led with “technically” ruling because the death of his eldest son had an overwhelming effect on the long-reigning Chogyal, who retired from public life and delegated most of his responsibilities to his younger son, Thondup, starting in 1941.

Thondup put to bed his plans of attending Cambridge and instead took up the mantle of a job he’d never expected to have while his father spent his time painting and meditating. In 1949, he worked with India to negotiate the treaty that would come to define his country’s contemporary image.

A year later, the Chogyal-to-be married a Tibetan noblewoman named Sangay Deki. The two would go on to have three children together, but the ensuing years were not entirely kind for Thondup. He attempted suicide in 1955 after a conversation with his brother in which the latter was dismissive toward the idea of a positive future for Sikkim, giving it a pessimistic (but ultimately prescient) twenty year life span. If this was the catalyst for the attempt, it was probably the blood that broke the camel’s back. Thondup never thought he’d be in charge of Sikkim, but since the mantle landed on his shoulders, he’d let it consume him. His success and the success of Sikkim were intertwined, one and the same.

Two years after Thondup’s children nearly lost one parent, tragedy struck; only days after falling suddenly ill, their mother died, leaving the Maharajkumar a widower with three young children.

With his father secluded from politics and his sisters abroad, the Chogyal-to-be was once again alone. But that, and the trajectory of his life, was about to change.

Next time: The American Queen of Sikkim.

Images

- Header Image: Photo of Chogyal Palden Thondup Namgyal by Alice S. Kandell, public domain; Namgyal Tsemo Monestry.jpg by Wikipedia user Kondephy, edited.

- Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0); this image is automatically free to use under the same license. Have fun!

- Gurudongmar Lake, North Sikkim, India.jpg by Wikipedia user Madhumita Das.

Read More

- Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom by Andrew Duff

2 replies on “The Last Chogyal of Sikkim”

Our present Chogyal is 13th Wangchuk Namgyal , 2nd son of 12th Chogyal Palden Thondup Namgyal.

Thank you for remembering our Chogyal. Long Live Chogyal PTN’s legacy.