Families love Mollie’s Nipple. Mormon mothers and fathers drive their children from miles away to see it. At 4,593 feet, it’s taller than most other nipples by nearly 4,593 feet.

I have a secret: It’s not a real nipple. It’s a butte, a weird flavor of tall hill with a high, flat top. It’s like a mesa, but thinner. In this case, a lot thinner. Honestly, it does kinda look like a nipple. This specific nipple butte, the one parents leave glowing Google reviews for, is in Washington County, Utah, a 31 mile drive from the town of Hurricane.

…but it’s not the only one. Utah has no fewer than seven mountains (and one butte) named after Mollie’s particular papilla, from the southern edge of the state to the northern. Trying to escape the reach of Mollie’s nipples in the beehive state is a fruitless endeavor. Even if you throw a canoe in the Great Salt Lake and row far enough from the shore, you’re still liable to come across Antelope Island, home to (can you guess?) Mollie’s Nipple.

Mollie’s got enough supernumeraries scattered far enough across the western United States to qualify for X-Men membership. So who was this titan of mamm-ifest destiny?

First, whoever she was, consensus says she’s not to blame for the scattering of her limited likenesses across the state. Some attribute the names to John Kitchen, an early Utahn pioneer and fucking psychopath who thought naming eight mountains after his wife’s nipples was a normal and cool thing to do. For all I know she was into it, but that’s not exactly the assumption I want to land on during Women’s History Month.

Other sources point out that “Molly” or “Mollie” was a contemporary slang term for “prostitute” in the same way that it’s now a slang term for a drug that makes you insufferable.

I like this angle because I think it’d be funny for ultraconservative Utah to play host to seven mountains named after prostitute boobs. I also like it because it lets me pretend that weirdo creeps like John Kitchen didn’t exist before the internet.

Maybe the Kitchen story is for real, and maybe naming western landforms after a particular element of his wife’s body was an activity the two engaged consensually in. But that’s not my head canon. I imagine a jaded and tired Mollie Kitchen, trapped in a covered wagon for days at a time and broken by the burden of rearing 32 children (the average back then; six months gestation was considered “more than enough”), closing her eyes in anticipation as her husband pointed to the sixth mountain in a row and exclaimed, “Hey, Mollie. Just named that one. Guess what it reminds me of?”, his eyes flicking vertically back and forth, hovering over one pole longer than the other.

The apocryphal Mollie’s trip would have been arduous, starting either in Arizona (where one mountain bears her name) or Idaho (where she has two) and trekking all the way through Utah to get to the other one. That’s the story I have to believe, if I believe it. One more hellish alternative is that the group started in central Utah, went as far north as their oxen would take them, naming nipples all the way, then turned around and retraced their steps, pointing and giggling at all the sky-high areolae they’d already identified before continuing south to find some more, maybe making several trips before Utah’s supply of nippular protrusions was exhausted. Either way, be it a family exodus or road trip gone awful, something brings our antihero and his hapless wife all the way to west-central Nevada, today the home of Mollies Nipple-South Peak. Kitchen was nothing if not prolific. If he had been born a hundred years later, tour guides in Kashmir and astronauts at NASA would scratch their heads at questions about “K2” and “Olympus Mons”. But they’d be able to tell you anything you need to know about Mollie’s Nipple.

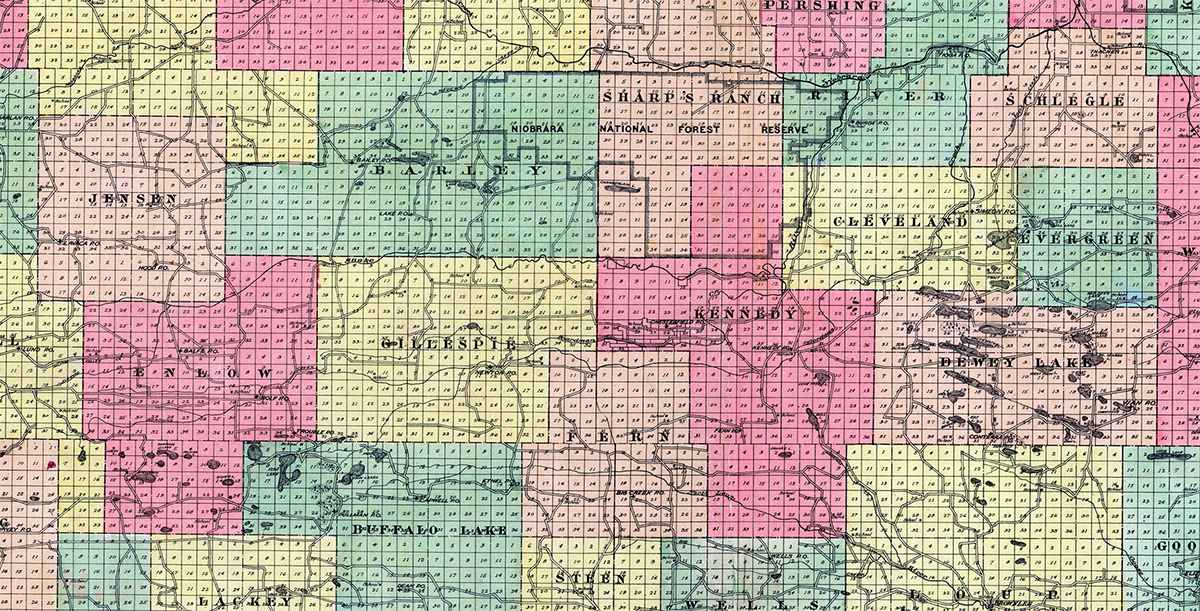

In all, Mollie has no fewer than twelve landforms that bear her nipple’s namesake. But she’s in surprisingly good company. In North America, at least forty mountains and hills include the word “nipple” in their names, the vast majority being found west of the Missouri. Not all of them outwardly belong to women, but it’s definitely a leading theme. And the pattern of naming mountains and buttes after women’s nipples skyrockets the closer we get to the Mormon corridor.

Within Utah, there’s Sadie’s Nipple, Elsie’s Nipple, Fern’s Nipple. They’d be so lucky to be as well-traveled as Mollie’s. Idaho is a site of contention. Two nipples there are contested by the presence of another: Janie’s Nipples in the south (set against our friend Molly’s), and then Sadie’s Nipple and Mary’s Nipple in the north. Between the two sets, there’s also Saint Mary’s Nipple, a name that somehow manages to be equally reverential and sacrilegious.

Most nipple mountains keep it simple, claiming “The Nipple” or “The Nipples” as their nom de terre. There are a few “Nippletop”s and a “Nipple Benchmark”. South Dakota, Montana, and Oregon each have a “Nipple Butte”, which is a real hoot for anyone who doesn’t know how to pronounce “butte” (it rhymes with “hoot”). Wyoming bucks the trend and plays host to “Dans Nipple”, underscoring their state motto, “Equal Rights”. Margaret Thatcher even gets a shout-out in Colorado with “The Iron Nipple”, which I concede could also be the canceled sequel to The Iron Giant.

If we expand our scope further, we’ll see a whole new host of mountains named for breasts in general, some with great names, like Washington’s “Teaters Bluff” or Texas’s “Squawteat Peak”. Honestly, if this is the path I choose to embark on, I’ll have sealed my fate for good. North American mountains named after nipples, that’s an afternoon. Mountains that look even remotely like breasts to the eyes of underfed and underslept pioneers? That’s a lifetime.

Perhaps the most well-known of these mammary massifs came to be in the 1800s when a group of French explorers or trappers traipsing through Wyoming came across three great mountains they christened “The Three Nipples”, or, in French, “Les trois tétons”. Today, they’re Wyoming’s famous Grand Tetons.

It’s worth noting that this, like the John Kitchen story, is just a theory. Other guesses are more respectful, attributing the peaks to local native Americans or people who didn’t think they looked like boobs.

As for the ones that are definitively named after choice features of the human chest, it’s tempting to criticize the men and women who named them, to accuse them of base unoriginality. But humans are bad at naming things. The “Grand Tetons” sound cool because they rest underneath a layer of obfuscation; they’re hiding behind French. “Los Angeles” sounds cooler than “The Angels” and “Chicago” beats “Onion”.

With the nipple mountains, there’s at least a layer of abstraction — we’re comparing the landform to something else. Often, we lack even that ability. When the Arabic-speaking people of Moorish Spain came across a massive stone promontory on the southern coast of Iberia, they called it Jebel-al-Tariq, “the rock of Tariq”. The land around the rock then changed hands, first to the Spanish, and then to the British, who knew “Jebel-al-Tariq” as “Gibraltar”. That was the name of the place. The rock was the “Rock of Gibraltar”. Run that back: the rock of the rock of Tariq.

Other such tautological place names include the Gobi Desert (“Gobi” is Mongolian for “desert”) and Lake Chad (“Chad” coming from the Bornu word for “lake”). They’re all over. “Lake Michigan” is “Lake Large Lake”. “Kodiak Island” in Alaska is “Island island”.

If a West Virginian town best known for a shitload of murder gets to call itself “Booger Hole” and not think twice, and five mountains in North Carolina don’t have to reconsider the name “Big Butt Mountain”, maybe we should refrain from being too hard on the forty-some nipples of North America. But John Kitchen gets the death penalty. Twelve is way too many, dude. Leave your wife alone.

Image

3 replies on “The Best-known Breasts of the West”

Where is the pictured one in the second paragraph?

Hey Mike,

It looks like this particular nipple isn’t the one just outside of Hurricane but instead one of the othere in the San Rafael Swell in Central Utah.

Here’s a post I found: https://www.uglyhedgehog.com/t-517074-1.html

Thanks for reading!

Sweet thank you sir. I found your write up a few years ago, but never clicked on the link until last night. Good times to be alive.