It’s December, 1976. Nearly eleven years after the January 1966 coup that brought him to power, Jean-Bédel Bokassa, President of the Central African Republic, is about to become Africa’s only emperor.

There had, of course, been emperors before Bokassa, stretching far into African history. The most recent, Haile Selassie of Ethiopia (whom the Rastafari revere as a Messiah), was deposed in a communist coup just two years earlier in 1974. A year after that he was dead, strangled by members of the communist Derg who reported death by natural causes.

Selassie’s Ethiopia was one of few African states to completely resist the yoke of European colonialism (and even then, the country suffered a years-long Italian occupation during World War II). For most of Africa, native sovereignty ended when European and Arab traders, explorers, and settlers planted their flags along the shore.

Africa had time on its side. Owing to a variety of reasons from a post-war furor for independence to a deliberate transition from political to economic colonialism, Europe agreed to loosen its hold on its southern neighbor. And once the European-imposed order started to crumble, the burgeoning independent states of Africa, many of whom had not been functionally independent for hundreds of years, usually presented themselves in the trappings of modern western republics complete with executive Presidents and elected legislatures. Many of these new republics fell short of democracy, but even as their leaders grasped autocratic power, as Bokassa had done, most did so under the guise of limited republican leadership, the Augustuses of Africa.

Jean-Bédel Bokassa was about to buck that trend. Given a legacy of African emperors to succeed, from Haile Selassie in Ethiopia to the defiant Shaka Zulu of Southern Africa and the incomparably wealthy Mansa Musa of Mali, Bokassa cast aside his neighbors’ forefathers in pursuit of the legacy belonging to one of his personal heroes, l’Empereur himself, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Bokassa saw himself as Africa’s Bonaparte, a leader deserving of all the power and prestige enjoyed by the Corsican military commander who was twice deposed by his vengeant military enemies. The M’Baka usurper’s country was new and not nearly as wealthy or powerful as Bonaparte’s France had been, but Bokassa refused to consider that his people may have found him to be deserving of any less pomp or circumstance than his spiritual predecessor.

And so, when the former army radio tutor announced his intention to crown himself Emperor, it followed naturally that this crowning must occur at a lavish coronation ceremony, one that completely eschewed any and all stops.

Vive l’Empereur

The event itself was exhaustively prepared, starting with the commission of a throne from a French sculptor willing to fashion a particularly ostentatious and massive eagle-shaped chair. The emperor would need somewhere to sit for the coronation, but he’d also need somewhere to plant himself on the way to the event, and so Bokassa commissioned an equally-ostentatious old school European-style carriage. Belgian horses were hired and moved to Bangui to pull it, and a team of Central Africans went to France for a crash course in equestrianism.

The imperial costumes made for the event were insanely expensive for the country’s standards but paled in comparison to the crowns made for the Emperor and the one wife of many that he’d selected to sit beside him as queen, the former bearing an 80 carat diamond and costing $2.5 million.

They’d made sure to cover the necessary royalty-themed needs of a coronation, but the event was, after all, a party, and the guests needed to be tended to as well. To that end, planners ordered 40,000 bottles of wine and 60 new Mercedes-Benz cars, the airfare for each running the committee a clean $5,000.

In all, the $22 million coronation amounted to a quarter of the Empire’s annual budget, though the bill would ultimately land at the feet of Giscard d’Estaing’s government in Paris.

Still, Bokassa wasn’t ready to stop there. He intended to grant himself further legitimacy and grandeur by holding the ascension in a Roman Catholic cathedral and by accepting his crown from the Pope himself. When the nearest cathedral and the furthest Pope both happened to be booked that specific day, Bokassa eventually settled for a non-papal coronation in a Yugoslav-built basketball arena.

Desperate to give an air of legitimacy to the coronation, invitations were sent to reigning monarchs all over the world, from the Shah of Iran (whose own days in power were limited) to Emperor Hirohito of Japan (who despite leading Japan through World War II still had a decade left in his own reign). In the end, only one foreign royal, the great-great grandson of Prince Johann I Joseph of Liechtenstein, made the trip.

Response to the event both within and without Africa was peppered with ridicule. Some thought Bokassa’s ascension would provide an excuse for him to retain wealth and power while leaving the actual on-the-ground management of the country to some imperial lackey. To these haters, he responded by naming a non-monarchical Prime Minister and giving him control of the country’s cabinet. Proud of himself for his constitutional monarch’s approach to the separation of governmental powers, Bokassa’s next move was to effectively neuter his new Prime Minister by creating a second, more powerful cabinet that reported directly to the Emperor.

Waterloo

An empire with so stupid a beginning deserves an appropriately stupid end. With the economy in freefall (it turns out a newly-independent nation can’t survive on Napoleonic roleplay alone) and imperial coffers lacking the quantities of cash necessary to pay government employees, Bokassa promptly sat the throne and turned his attention to unsatisfactory high school exam scores.

Some Centrafricains suggested the scores were the natural result of a national reliance on French expatriates and French-trained teachers for the education of culturally-distant Central African students thousands of miles from France, but Bokassa saw it differently. In a supposed attempt to ameliorate the issue, he mandated all students immediately comply with a new school uniform policy. The uniforms were standardized nationwide and, oop, as it so happens, manufactured exclusively by the emperor’s personal industrial apparatus.

When the civil servant parents the state had been unable to pay were shockingly unable to themselves afford these new uniforms, the schools excluded their students from classes. Newly burdened with the boon of free time, the suspended high school students banded together with their university peers, presaging the beginning of a series of nationwide riots.

Bokassa’s Potemkin Paris wasn’t so flimsy as to be crushed by disuniform high school students alone, but this movement of unrest and disobedience spread throughout the country, the uniform issue setting fire to fumes gathering since the emperor’s brazen power play/Napoleon cosplay combo move. Eventually, in April 1979, a mass student gathering at the university ended in over 150 arrests, filling Ngaragba Prison and leading to the severe beating and humiliation of many of those arrested, and ultimately to the deaths of at least eighteen.

The violence led to global condemnation. Some sources claimed to world media that the emperor himself was present for the beatings. Bokassa’s government denied the deaths entirely, explaining away the missing people by claiming the protestors had instead “crossed the river to Zaire”, disappearing into the Congo jungle.

France called for a commission of inquiry to evaluate the events of the Ngaragba Prison Massacre. Many in attendance remained sympathetic to Bokassa and urged him to act in such a way that he might cure the growing divide while maintaining his position on the throne. Some French agents suggested the emperor execute the underlings who had committed the violence to save face. He refused.

Once they’d arrived in Bangui, the inquiry team’s members took to interviewing members of Bokassa’s political and military inner circle, all of whom corroborated the Emperor’s official line. But when the inquirers sought after opposition figures, their requests were denied.

Bokassa himself had a simple explanation for the chaos: his ex-wife was lying in an attempt to defame and slander him.

Ultimately, without help from the Centrafricain government, the inquiry continued undeterred. When it was finally published, the report released by the inquiry put forth that at least 150 people, no less than one hundred of them children, had died in the January conflict, including the names and photos of those who perished. Particularly egregious was its account of the murder of an 8-year-old boy by a Centrafricain general.

Present and former officers of the country began abdicating their loyalties in and before the wake of the report. Deposed President David Dacko, who had since been rehabilitated and acted as an advisor to the emperor, escaped to France.

After Bokassa refused French invitations to resign, the French government, under increasing pressure from the public and from opposition politicians like Miterrand, decided first to pull French financial backing of Bokassa’s regime and then to draw up plans for an invasion. After deliberation, they selected the conveniently close-at-hand former President Dacko as their anointed successor.

Spurned by the state of his heroes Napoleon and de Gaulle, Bokassa turned once more to Libya. He flew to Tripoli to meet with Muammar Gaddafi, who, having been burned once before by Bokassa’s advances, was receptive to the overture out of interest in Centrafrique’s military airfields and uranium supply.

The two countries signed a treaty wherein Gaddafi’s government agreed to pay the troop salaries and academic scholarships otherwise at risk, saving the empire from the French financial stranglehold. Unfortunately for Bokassa, the deal would never see fulfillment. France and the Centrafricain opposition took advantage of the Emperor’s departure and executed Operation Barracuda, the airlift of several hundred French paratroopers into the country. Once on the ground, they disarmed the country’s guard forces without injury and successfully returned David Dacko to the helm of the nation.

Less than three years after its founder’s courtside coronation, the sun set on the Central African Empire.

Next time: The Exile

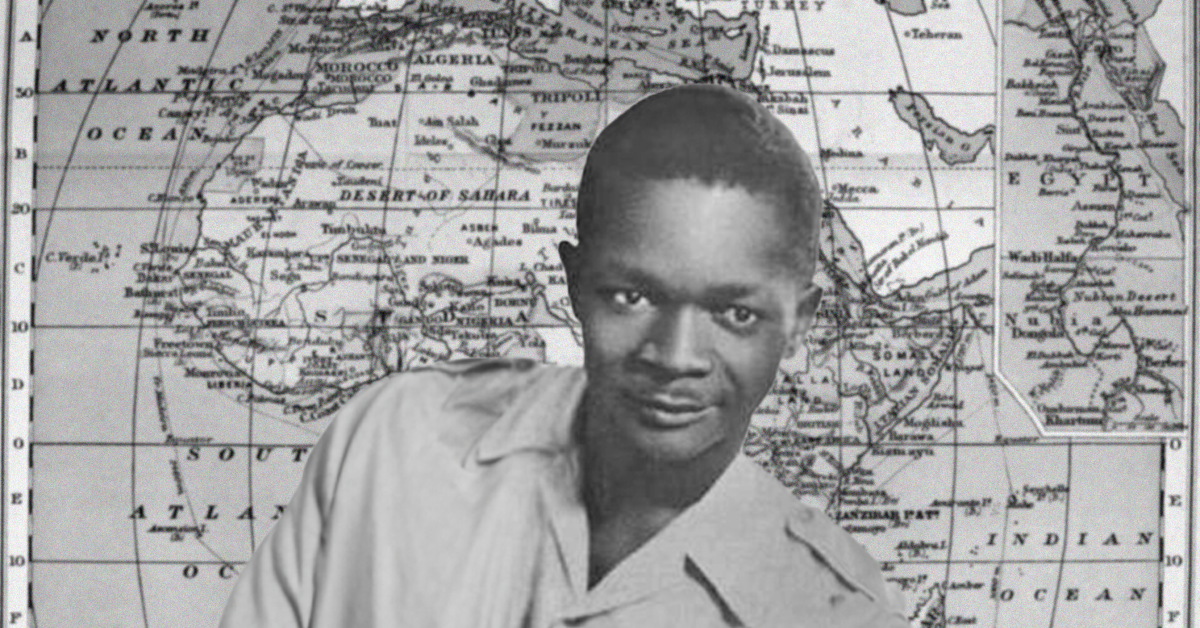

Image

- Bokassa_evening.jpg by Wikipedia user Best

- Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

Read More

- Bokassa Crowns Himself Emperor In Rich Central African Pageant from The New York Times

- Bokassa Is Reported Overthrown In Coup in Central Africa from The New York Times

- Central Africa: Mounting a Golden Throne from TIME

- Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa by Brian Titley

- In Central Africa the Sun Sets on a Republic and Comes Up on an Empire from The New York Times

- With Fanfare of Trumpets, Africa Gets a New Emperor by J. Regan Kerney for The Washington Post