Johann Blumenbach’s next project was the big one. The prolific German physician had built a successful career out of comparing the anatomies of humans and their animal cousins. Now he’d set out to compare humans to other humans. His goal? To create a complete and comprehensive tier list of human races.

Today, haters will tell you that the science-driven corralling of humans into neat little boxes is beyond controversial and old-fashioned, but at the height of Blumenbach’s career in the 1790s, the task was a new and worthwhile challenge, real hot shit. Take care before you judge a white man trying to sort people by race — Blumenbach, a well-respected anthropologist, maintained that all races were approximately equal in cognitive ability, arguing that all human subgroups had equal aptitude for intelligence and creativity. Pretty progressive for 1795, right? Of course, his faith in equality stopped there. Intellectual equality? Absolutely. Physical equality? No way in hell.

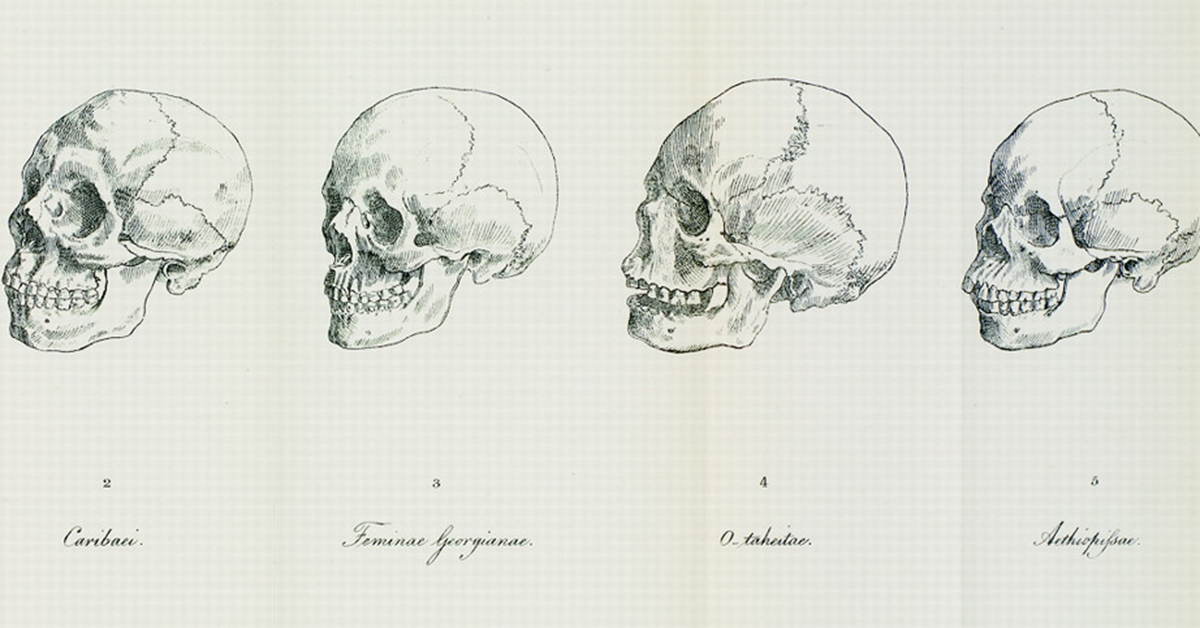

Years of practice had made Blumenbach well-versed in the comparison of bones. For his work here, he turned immediately to an extensive collection of skulls. I don’t have to explain to you that white dudes with a shitload of skulls are trustworthy by nature.

Among this collection of crania, one specimen stood out as uniquely special. It was, in Blumenbach’s own words, “handsome and becoming”, a real sexy skull. It came from a woman who had lived and died in Georgia, a country in the Caucasus Mountains between Turkey and Russia. Because of the skull’s natural beauty, Blumenbach reasoned that the race of people it had belonged to must sit at the top of the human physical hierarchy. The people of the Caucasus, the Caucasians, were number one. The best anyone else could hope for was second place. But Blumenbach’s brain wasn’t done working. He lived in Germany, 1600 miles away from Georgia, separated by mountains, seas, and several empires. But he’d never felt closer. The Georgian woman’s skull was very pretty. Blumenbach liked to think his skull was pretty too. If Caucasian skulls were the prettiest, and Blumenbach could only imagine he had the prettiest skull, by God, he must be Caucasian.

This is the absolutely real justification for the Caucasian super-race. Every time you’ve seen that word used to describe people who look like me, you were witnessing the legacy of one vain long-dead man and his macabre collection of longer-dead skulls. Blumenbach’s unshakeable belief that he was the prettiest girl at the prom rebuilt the foundations of western racial theory. And hundreds of years of hard science later, it’s still bouncing around our own skulls.

The progenitor of the Caucasian origin theory did not believe that his race of structural supermodels were intellectually superior to their neighbors. His successors couldn’t have given less of a shit. To a scientific racist hopping around in the late-18th and early-19th centuries, Johann Blumenbach’s hypothesis was the holy grail, a critical missing piece in their superior race’s origin story.

Even if Blumenbach had believed in the cognitive supremacy of his Caucasian supermen, he had no interest in investigating it; his domain was aesthetic perfection. Samuel Morton’s operation was different. Morton was an American physician and scientist cut from the same cloth as his German counterpart, sharing his interest in the categorization of race. Morton also maintained a collection of skulls (his was much larger, he’d be proud to point out) and made a habit of measuring the space inside of them, deciding that the more cavernous domes of the so-called Caucasians were evidence of advanced cognitive abilities, and thus mental superiority. Where Blumenbach left half of his picture purposefully unfinished, Morton used his predecessor’s own technique to fill it in.

The two men had different philosophies regarding the origin of race and man. Morton argued that races of men had been designed by a creator for their particular environments, that Indians had been purpose-built for India, Europeans meant for Europe. Blumenbach’s opinion was that his Caucasians were the original humans and that all other races degenerated from a Caucasian origin. His perspective is unique, not only compared to Morton’s, but also to those who took up the torch of scientific racism. White supremacist social darwinists usually suggest that the Caucasian race was tempered and improved by evolution while others stalled.

It’s important to take a break and acknowledge that these theories were built with an excessive amount of turbo assumption. Blumenbach did not investigate the evolution of skulls, he merely rated them on their attractiveness. Morton’s similar background in skull-measuring does nothing to afford him the authority to make his claims. Later science has not supported the idea that skull size correlates with intelligence, and subsequent inquiries have called into question the accuracy of Morton’s original measurements. In any case, this is guesswork, the penis envy of race science, but it’s important because both of these men are building stories. The human brain works with what it has, and the connections it builds between ideas are not always beholden to accuracy. In the absence of real knowledge, we’re willing to accept constructed narratives. When we don’t know the answer, a guess will suffice.

Morton’s and Blumenbach’s were just two of the stories that proponents of this burgeoning field put forth over the next hundred plus years. Another theory, one that became particularly popular in the 1800s, invoked the biblical story of Ham, a man whose son may or may not have been cursed by God after Ham walked in on his drunk father, Noah, completely naked. As though an eyeful of dad dick weren’t punishment enough, Noah demanded that Ham’s son Canaan be eternally cursed to servitude.

Most modern bibles keep the story short, but some sources suggest what happened in Noah’s tent was considerably fouler than King James is comfortable printing. Whatever occurred, the story is clear that it was enough to outrage Noah into asking for God’s condemnation of his grandson. One thing the story is less clear on is geography. Canaan’s children, the Canaanites, are referenced frequently in the Bible but rarely geographically delineated. The people historians refer to as the Canaanites lived in the southern Levant, in modern day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan, the setting of most of the Bible. In the age of scientific racism, the narrative shifted.

Much as Johann Blumenbach saw a perfect skull and drew a line in his mind to his own perceived perfection, the scientific racists of the 1800s and the unscientific racists who preceded them saw the position of servitude the Transatlantic Slave Trade imposed on Black Africans and drew a line to the Canaanites, the people cursed to serve. In both cases, the connection was made-up and assumed, but both fit the needs of their creators. Slavery is and was a horrific institution inextricable from the extreme suffering and trauma it caused. You didn’t need a guy whose last article’s headline started with the word “Butthole” to tell you that. For most people, it’d be an unfathomably difficult thing to put another human being through. But if those humans were built for slavery, destined to it, subjugation becomes easier on the mind.

Pro-slavery figures continued to cite the Curse of Ham to justify the horrific acts imposed on enslaved people up until abolition, despite the fact that the Bible never makes the connection between Canaan and Africans. The narrative was so powerful that, until 1978, the Mormon Church still used it to justify refusing priesthood to Black congregants.

Proponents of the Ham theory sometimes used Blumenbach’s “Caucasian” label, but others preferred “Aryan” a term previously applied specifically to an ethnic group that moved into and conquered India over a thousand years before the events of the Bible. You probably know it from its usage by another German who tied his white identity to an unrelated group of Asians.

Whichever designation was used, these prehistoric superwhites were the original ancient aliens, responsible for every impressive building and cultural site in areas later inhabited by non-whites. While the modern conspiracy theory and harbinger of the History Channel‘s descent into insanity is used today to argue against the ability of nonwhite humans to construct awe-inspiring structures, early anthropologists weaponized these same arguments against the native Africans who built wonders like Great Zimbabwe.

Believed to have been the seat of power of a long-gone empire, Great Zimbabwe still stands as a set of ruins in the center of the modern country named after it. Having investigated the city after its discovery by Europeans, site director Theodore James Bent formally alleged that it and all other ruins of its kind had been built, not by native Zimbabweans, but indeed by members of our mythical white super race. He speculated that these ancient milquetoast marauders would have borne similarities to the Pelasgians, a vaguely-defined and heavily mythologized collection of pre-Greek people who lived in today’s Greece. In other words, the professional in charge of investigating Great Zimbabwe decided it was more likely to have been built by mythical humans than local Africans.

Proponents of the ancient white tribe hypothesis were locked in. And much like today’s ancient alien theorists see evidence of extraterrestrial assistance in every big art project and curiously-shaped hill, this vanguard found evidence for their universal whites everywhere they looked. Ethnic groups seen as culturally distinct from those around them, particularly those that fit the mold of Western European success, were thought to have been the descendants of white progenitors. Labels of “partial whiteness” were applied to groups like the Ainu of northern Japan, the Brahmin of northern India, and the Maori of New Zealand.

The creation of this semi-white label had two useful functions: first, it provided supposed evidence for the white tribal hypothesis, but second, it further robbed non-white people of their accomplishments. If your hypothesis is that white people are the most successful, and every non-white person who demonstrates success then becomes white, it’s gonna be harder to disprove that hypothesis. Accomplishments attributed to the Brahmins of India were no longer Indian accomplishments, but white accomplishments by way of partial Indian ancestry.

The Brahmins have a particularly apt place in this discussion in that their relationship with the white tribe hypothesis is a symbiotic one where both parties benefit. This imported idea that the Brahmins are inherently superior to those around them is one they’ve been selling themselves for centuries. In the traditional Indian caste system, the Brahmins occupy the top level of the social pyramid. When the British arrived, their willingness to work with these existing ideas of hierarchy expedited imperial organization. Previously, the Indian caste system was a remarkably complex collection of groups big and small. Ideas of hierarchy and supremacy were embedded in Hindu culture since the religion’s early days, but it wasn’t until the British showed up that these hierarchies were made rigid and enforced by law.

Where colonizers didn’t have existing hierarchies to work with, they created them. In Rwanda, the aesthetically-distinct Hutu and Tutsi people lived (relatively) peaceful lives beside each other, sharing similar Bantu language and cultural backgrounds. Then, Belgian government officials, armed with knowledge of the white tribe hypothesis, informed the Tutsi that their unique appearance was attributable to their descent from the white kings who had once lived where they do now. While the Belgians ruled, privilege and authority was afforded to the minority Tutsi over the majority Hutu.

The stories of the Brahmin and Tutsi people are similar so far, but they diverge dramatically in their transitions to post-colonial self-rule. Since its departure from the British Empire, India has struggled to throw off the yoke of the caste system its overlords had reinforced, and caste remains one of the primary indicators of wealth and wellbeing in India today. I suspect you don’t need me to tell you how the Rwandans have fared. When the Belgians left and the right of self-governance was afforded to the people, the Tutsi hierarchy fell and a Hutu government took power. This government used the Belgians’ words of praise and common origin against the Tutsis and labeled them invaders who had to be expelled. Both groups had lived side-by-side in Rwanda for longer than anyone remembered, but this imposed narrative of white origin and decades of European government drove them apart. Conservative estimates put the death toll of the following Rwandan genocide at around half a million humans.

Colonial regimes used stories of inherent superiority as a means to control indigenous people wherever they ventured. I’ve labeled this debunked idea of an ancient, earth-spanning tribe of white folks a “hypothesis” so far, but hypotheses are created with the goal of being scientifically tested. Once the white tribe idea was out in the air, proponents weren’t interested in its verification, especially as they benefited directly from its assumed veracity. For a key example of that mentality, let’s jump back to Great Zimbabwe.

From 1965 to 1979, the country that housed this world heritage site was known as Rhodesia, a white supremacist, apartheid nation named after Cecil Rhodes, a man who pioneered British colonialism in Africa and built a diamond monopoly that still dominates markets today. The entire Rhodesian system, from government to economy to culture, ran on the idea that the native Black Africans were inferior to the ruling white elite. For its existence, the government’s official position on Great Zimbabwe and other ruins like it was that they were constructed by ancient white dudes. When archaeologists started poking around and raising disagreement, the government sent them away.

I wrote a piece earlier this year about a Bosnian pseudoarchaeologist who maintains that a very large hill in Bosnia is actually the world’s oldest, largest, and most interesting pyramid. He’s wrong. All the science, all the archaeologists, all the geologists say he is. But he persists, because the message is so potent: if this hill is all the things he wants it to be, then ancient Bosnians were very powerful and super cool. He is not an ancient Bosnian, but he’s drawn a cultural connection to them. The Rhodesian government was doing something similar, but this time mapping the inferiority of the local people with what they could not have possibly done. In the Bosnian pyramid case, disproving the pyramid would damage a feeling of superiority. Here it’s the opposite. If medieval Zimbabweans could have built this without white assistance, they’re not as inferior as we thought they were.

Rhodesians didn’t believe Great Zimbabwe was the work of white people because the science pointed that way, they believed it because they wanted to, and because it suited their own interests. The British and Belgians had similar motivations for their constructed hierarchies in India and Rwanda; they chose stories that fit their goals of rapid conquest, organization, and exploitation. Johann Blumenbach called himself a scientist, but found himself led by this same impulse when he identified his most perfect skull and, overvaluing himself tremendously, assumed his must be just as perfect. It’s beyond inaccurate to suggest that white people built Great Zimbabwe. It’s morally wrong to argue the superiority of one ethnic group or caste against their neighbors. And it’s incorrect to call white people Caucasians.

No matter how you cut it, delineating race is always going to be a messy job, but this attachment to a centuries-old Caucasian origin theory only makes it messier. If Europeans on one side of the Caucasus mountains are superior because of their Caucasian origins, what about their neighbors on the other side? The Caucasian myth has spawned a unique hesitancy where Europeans quick to distance themselves from different-looking people have had difficulty doing the same to Arabs and others of middle eastern descent. That’s part of why survey writers still have trouble deciding whether or not Middle Easterners count as white. Even more confusing is the situation for modern Caucasians, the Georgians, Armenians, Azerbaijanis and members of myriad Russian ethnic groups who, depending on source, are either definitively not white or as white as possible (AWAP for short).

At first glance, it’s easy to label these theories as misguided science, the flawed beginnings of an eventually-sturdy field. But it’s important to see the impulses that guided these men for what they really are: attempts to repair the dissonance that stretches between narratives of white superiority and evidence to the contrary. Men who questioned the ancient Egyptians’ ability to understand astronomy and division of labor never bothered to doubt the Roman command of aqueduct irrigation and concrete production. Columbus sailing great distances to discover the new world acts as evidence for his race’s inherent superiority, but Austronesians doing the same thing hundreds of years earlier is not evidence of theirs — at best, it’s proof that they might be whiter than their neighbors. Better, but never best.

So what do we do? How do we dump “Caucasian”? For most of us, it’s probably not even a problem. I don’t think I’ve ever called myself Caucasian. Even without all the aforementioned baggage, it sounds absurdly and uncomfortably formal, like men who refer to women as “females”. Writing for The New York Times, Shaila Dewan points out that the equivalent names for other racial groups, Negroid and Mongoloid, have long fallen out of favor, yet Caucasian sticks around. The only benefit the term bears over “white” or “European-” is that it hints at the sort of mythic, ancient origin that would excite Indiana Jones. But this origin is just that: a myth. We should move on from “Caucasian” because it’s a term built on bullshit, and because it’s the right thing to do. If nothing else, we have to ask: do we really want our identities defined by a centuries-dead man and his hot bone fetish?

Read More

- Can you tell a person’s race from his or her skull? by Brian Palmer for Slate

- Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson

- Has ‘Caucasian’ Lost its Meaning? by Shaila Dewan for The New York Times

- The myth of a ‘lost white tribe’ by Michael Robinson for The Boston Globe

- The pernicious myth of a Caucasian race by Joel Dinerstein for the Los Angeles Times

- Race – The Power of an Illusion from PBS