On September first, 1939, Hitler’s army crossed Germany’s eastern border and entered Poland, an invasive act of aggression that marks the official beginning of World War II. The invasion and subsequent occupation by German forces would become internationally well-known during the conflict and following its end. But the Germans weren’t alone.

Sixteen days after the German invasion started, the Soviet Union, Poland’s gargantuan neighbor to the East, followed suit, the motherland emulating the fatherland. The Red Army that rapidly canvassed Poland included some four thousand tanks and an aerial presence that dwarfed the Nazis’ own. The Soviet front marched forward until its troops met the Germans in the middle of the country, at which point both sides… stopped and continued about their business. The two were in cahoots.

Just one week before the Nazi German army began its march into Poland, the German foreign minister, Joachim Ribbentrop, flew to Moscow to meet with his Soviet counterpart, Vyacheslav Molotov (the spicy beverage namesake). There, the two put together a non-aggression plan: you don’t fuck with me, I don’t fuck with you. Also, minor detail, we’re going to carve up Poland and digest each half whole. And we’re not going to tell anyone, because that would ruin the surprise.

Again, the German invasion is pretty well-known. Hitler’s motivation for the capture of his second-largest neighbor was the same as his motivation to systematically gobble up every territory within spitting distance of the fatherland; lebensraum (living space), the weird concept that Germans were too cooped up inside Germany and needed a little bit of Poland to stretch their legs.

Officially, the German invasion was a response to a false-flag operation involving bullshit Polish soldiers (actually SS officers in Polish uniforms – sneaky!) who attacked a German radio station and played mean messages. Unimaginable – like having the gall to broadcast Chocolate Rain on Chicago police frequencies. The Nazis even left a trail of dead prisoners dressed up like German soldiers to seal the deal. This story’s not repeated often today, since it’s overshadowed a little bit by our knowledge of lebensraum and a lot bit by the fact that it’s all bullshit. According to The Atlantic, regarding the operation, Hitler himself said “Its credibility doesn’t matter. The victor will not be asked whether he told the truth.” More on that later.

Meanwhile, in the East, the Russian narrative on their invasion wasn’t much different. Officially, they were there on an aid mission to the region’s ethnic minorities. In the words of army big boss Commisar Kozhevnikov in the Soviet military newspaper, “the Red Army stretched out the hand of fraternal assistance to the workers of Western Ukraine and Western Byelorussia freeing them forever from social and national bondage.” Nothing says freedom like intense and long-lasting military occupation. Even after the war, the Soviet Union refused to admit that it had conquered or annexed Polish territory. They were just trying to be nice.

For most areas of the world, the idea of two unrelated and largely ideologically-opposed countries collaborating to completely destroy the existence of another nation is inconceivabile — Germany lost territory after each of the World Wars, but it didn’t disappear. For Poland, though, this wasn’t even the first time it had happened.

The First Time it Happened

In 1772, four years before the invention of America, the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian Empires decided to put aside their differences and collaborate on a group project: stealing pieces of Poland while she wasn’t looking. The three drew up an agreement and promptly attacked, pressuring the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to recognize the tripartite landgrab. Against the wishes of its people, Poland complied, having given up over a quarter of its territory.

Twenty years later, Poland decided it had grown up and was going to be a strong new country, complete with a new liberal constitution. The country’s conservatives disagreed, but they didn’t want to act on their disagreement themselves – they didn’t need to, they had a friend who was a lot bigger and stronger than they were. The conservatives gathered and wrote to Russia, asking their neighbor to intervene and replace the sexy young constitution with the old one. Russia, still hungry for a piece of Poland pie, readied its sticks and guns and rushed to the border, where they found a similarly land-lusting Prussia ready to join in. The two occupied the country and forced Poland to concede another set of territories, over forty percent of its land pre-1772.

Poland was angry; the two concessions together left her with significantly less than half the land she’d come with. In response, an insurgency rose up within Poland against the occupying powers. Unfortunately for the Polish partisans, the occupiers were a lot bigger and stronger.

Not interested in dealing with further Polishness, Russia and Prussia agreed this time to completely digest the remainder of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and, as a gesture of nicety and goodwill, they invited their friend Austria to join in the feast. On October 24, 1795, the three powers formally deleted Poland from the map.

When I first read about the partitions of Poland, I assumed they were a weird blip on the historical radar, a short slice of European history. To my surprise, they were not that. Poland resurfaced briefly as a Napoleonic client state in 1807, a status transferred briefly to the Austrians between 1815 and 1816. Exempting that historical hiccup, though, Poland’s erasure lasted from 1795 to the end of World War I in 1918. Over a century without Poland based on the whim of three buds.

Naturally, when Poland finally reappeared in 1918, its neighbors were a bit miffed at having lost their Polands (its neighbors here being Russia and Germany – the Austrian Empire was obliterated (but still not erased) after World War I). Prussia and the Russian Empire came together to destroy Poland in 1795, and in 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union played their fun little game a second time.

The Second Time

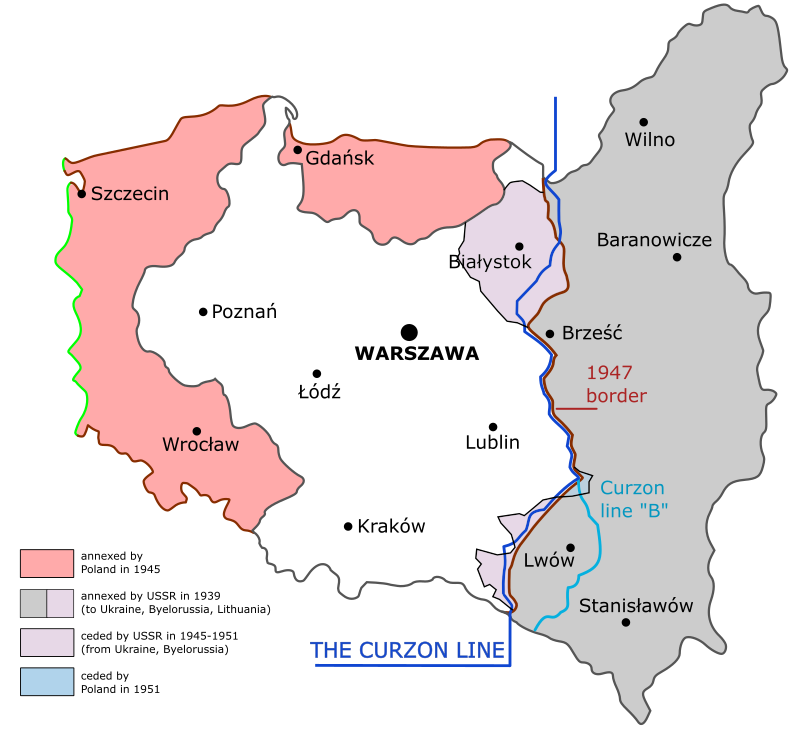

If anything speaks to the unique space Poland had in the mind of European despots, it’s the treatment it received each time it was invaded. While most territories under German and Russian occupation during World War II were simply occupied militarily or replaced with friendly puppet governments, Poland was torn apart wholesale. For the Nazis, most of the occupied Polish territory became the General Government, an integral piece of the German Reich. In the Soviet Union, Eastern Poland (known sometimes as the Kresy) was sliced up and implanted onto the Soviet Republics of Belarus and Ukraine. No more Poland! 🙂

As the war raged throughout Europe, Poland continued to play unwilling host to the worst atrocities of the Nazi regime. It was occupied Poland where the Nazi SS and Einsatzgruppen began the systematic murder of civilian Jews and other minority groups that we now know as the Holocaust. Many of the earliest concentration camps and Jewish ghettos were established in Poland. Each of the six facilities officially designated as “extermination camps”, including Auschwitz, were built on Polish soil.

German occupation is estimated to have led to the deaths of one in five Poles, including ninety percent of the country’s Jews. Of the Jewish people who died in the Holocaust, as many as half may have been Polish citizens.

The Eastern Front

In June of 1941, Hitler’s armies pushed past the agreed-upon dividing line and invaded the Soviet Union in the surprise attack known as Operation Barbarossa. What the Germans had hoped would be a rapid victory turned into a slow and costly winter counteroffensive that, alongside American involvement post-Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, would eventually turn the tide of the war against the Axis Powers.

Less than four years later, in spring of 1945, the Soviet Union and her western allies met in a warm embrace in Berlin, officially ending the war in Europe. At a series of conferences held all over the world, the “Big Three” allied leaders, America’s Franklin D. Roosevelt, the United Kingdom’s Winston Churchill, and the Soviet Union’s Josef Stalin (choose your fighter) would come together to make big decisions regarding the fate of Europe and the rest of the post-war world.

Germany, as the loser, would be required to relinquish its hold on the territories it had invaded and occupied, including western Poland. The Soviet Union, rebranded as heroes and co-victors, would be allowed to keep their piece of Poland as a souvenir.

Feeling generous, Stalin pitched Poland a deal: they could have some extra land to make up for the cities and fields Stalin had stolen, but there’s a tiny catch: it’s not Soviet land, it’s German. Like, German German, not occupied Poland. All of the cities are German. The people who live there speak German.

I’m sure it’ll be no problem. The other allies agree with Stalin – this is a good idea and a solid plan. So, between 1945 and 1950, between twelve and fourteen million ethnic Germans were forcibly removed from their homes in what Historian R. M. Douglas claims may have been the “largest single movement of population in human history”.

This part of the story comes with a lot of asterisks. First, it’s important to remember that the people who are being removed from their homes and forced to move somewhere unfamiliar are not, by and large, Nazi Party members – they’re German civilians. Second, it’s possible to recognize that forcing Germans out of their homes is a bad thing while still acknowledging that the crimes committed by Germany and the Nazi regime were some of the worst atrocities the world has ever seen.

In the effort to move twelve to fourteen million people from one place to another, the allied military authorities in charge of the population exchange felt it was important to have central locations to gather and keep people while they were waiting to be moved, somewhere they could concentrate the Germans. But where? Did you guess the Nazi concentration camps? You’re right! The occupying allied forces repurposed the old, drab, concentration camps of the Holocaust with updated cute concentration camps for a different ethnic group.

Using old concentration camps as new concentration camps is… clearly suboptimal, but I should probably make the distinction that the allies weren’t explicitly attempting to exterminate the Germans — this was about moving them somewhere else, which is a far cry from the final solution. All the same, deaths caused by military negligence and carelessness are still deaths, and scholars estimate that between 473,000 and one million people died in the population transfer. At least tens of thousands of those who stayed in the concentration camps were used as a source of allied forced labor, a page right out of the Nazis’ depressing playbook.

Overall, by the time it was over, atop the massive pile of the dead, Germany was left with the largest homeless population in the industrialized world, and many of those ethnic Germans who were moved to Germany now found themselves destitute and impoverished, including Oskar Schindler, the famed listmaker who saved 1,200 Jews from the Holocaust.

In 1946, the Nuremberg Trials were underway, designed to punish the Germans who contributed to massive amounts of death and suffering during the Holocaust and World War II and definitively determine the rules of war. In the documents published after the trials’ end, the judges wrote that “deportation and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population” constituted “crimes against humanity”. Some 500 miles away, British philosopher Bertrand Russell asked “Are mass deportations crimes when committed by our enemies during war and justifiable measures of social adjustment when carried out by our allies in times of peace?”

Meanwhile, in Moscow, the Soviet Union celebrates both the end of the war and having definitively secured their portion of Poland, a massive division of a country taken by military force in concert with the Germans. At the war’s end, Germany’s invasion of Poland was condemned, but why? If we’re to believe it’s because it was wrong and unlawful, the Soviet invasion surely should have been reversed as well; theirs was hardly unlike the Germans’, they weren’t on their way to fight the most brutal regime in modern European history, rather they had partnered with them to split someone else’s territory.

Here, the simplest answer is probably the most accurate; the Soviet Union got to keep the territory because they went on to win the war, regardless of the steps they had taken prior to their involvement in it. In the coming decades, Stalin’s plan to push Poland west worked out for him, serving to economically damage Germany in the years to come and to prevent any possibility of Poland and Germany working together against Russia’s interests. By the looks of it, teaming up with the Nazis was a net positive. They were the victors, and to the victors went the spoils.

The New Poland

Today, Poland is still marked by the territorial transfer that followed one of its most traumatic eras. Much as hundred-million year old plankton and the legacy of slavery have a lasting effect on politics in the United States, the significantly more recent movement of borders has lasting political consequences in Poland. The part of the country that once belonged to Germany is mostly rid of its former occupants, but the people who live on the soil they occupied vote differently than their peers in the Poland that always ways, so much so that the border between the two is still clearly identifiable on recent election maps. The same can’t be said about neighboring Belarus, who retains a sizable piece of the former Kresy, but that may be less a marker of cultural unity and more about how the country is, in practice, the last of Europe’s authoritarian dictatorships.

I’m not going to delve into why the borders of 1945 continue to influence the politics of 2020. To do that, I’d have to learn, and I already made you read this far. What’s more important is that we recognize the impressive staying power of history; two invasions and a victory seventy-five years ago determined a border that still stands today and seems likely to stay that way going into the near future. The legacy of the brutal population transfers that occurred three-quarters of a century ago continue to burn bright.

History isn’t just what happened a long time ago, it’s how what happened then continues to impact people who are living now. Josef Stalin died in 1953, and Hitler died alongside the German war effort in 1945, but the Poland they built together still stands, seventy five years after they shaped it.

Read More

- 80 Years After Germany’s Invasion Of Poland, A Look At World War II’s Toll On The Country by Jeremy Hobson and Jackson Cote for WBUR

- Partitions of Poland from Encyclopedia Britannica

- The European Atrocity You Never Heard About by R.M. Douglas for the Chronicle of Higher Education

- The forgotten story of when the Germans were the refugees by Adam Taylor for the Washington Post

- When Poland was lost: The Soviet invasion 80 years ago by Magdalena Gwozdz-Pallokat for Deutsche Welle

- World War II: The Invasion of Poland and the Winter War by Alan Taylor for The Atlantic

Images

- Curzon line en by Wikipedia user radek.s, no changes made

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

- Rzeczpospolita 1938 by Wikipedia user Halibutt, edited

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

- Rzeczpospolita Rozbiory 3 by Wikipedia user Halibutt, no changes made

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

- Wrzesien2 by Wikipedia user PoeticBent, public domain