Did y’all notice there was an election? It’s over now. You might’ve missed it. Following an absurdly long five days, we know Joe Biden has enough electoral votes to be named the next President of the United States. In the end, it was Pennsylvania’s twenty electoral votes that put him over the top, but in the nights following the closing of the polls, all eyes were on Georgia.

The peach state is notable this year because it looks like the state’s votes are going to Biden, which is itself notable because Georgia hasn’t voted for the Democratic candidate since Bill Clinton in 1992, and even that was a fuckup probably attributable to Ross Perot’s third party bid. It’s kind of taken for granted that the states of the deep south vote Republican.

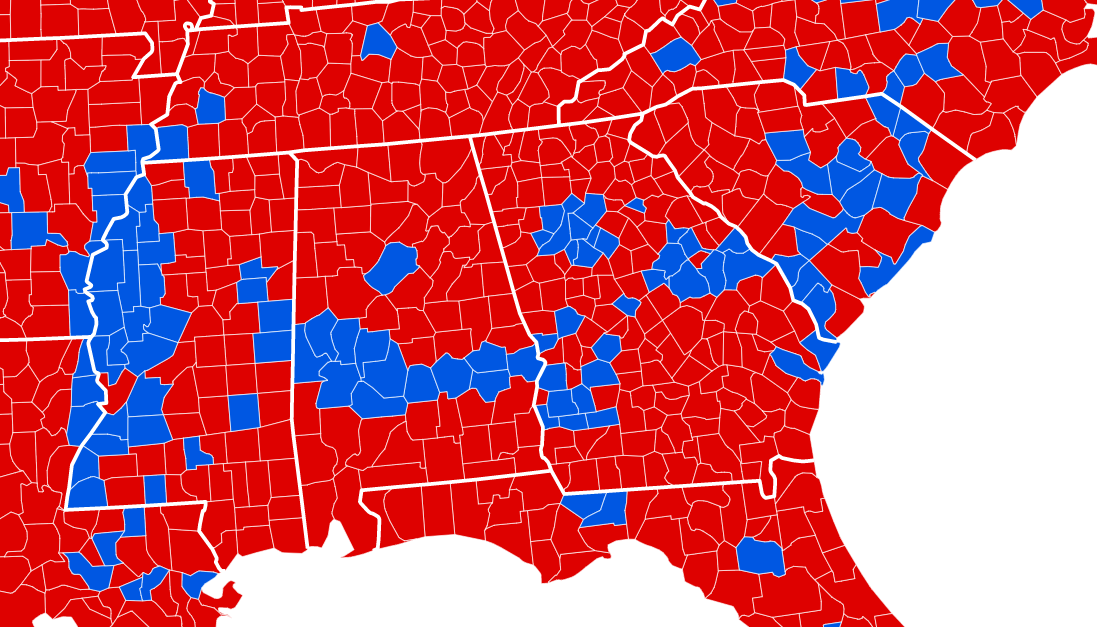

But even in still-solidly Republican states like Mississippi and Alabama, some counties are solidly blue. Part of it’s the urban-rural divide; dense cities tend to skew Democratic, less populous rural communities vote Republican. But across the south, from Louisiana to Virginia, there’s a pretty contiguous blue line that never fails to make an appearance on electoral maps. It’s not an unbroken wall of cities, it’s the black belt, and to understand it, we have to go back about a hundred… million years.

It’s the cretaceous period. There are dinosaurs everywhere, and North America looks different. It’s two North Americas, split by a sea that runs straight through the plains (God’s statement on West Dakota). The shallow body of water curves right through the American southeast, with a shore running through the middle of Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. At the time, the coast was a local favorite for marine plankton, who would forever impact American politics by living, eating, and dying a ton.

Over the next hundred million years, the earth’s temperature and atmosphere would change a lot, and the water gradually moved out of the plains and deep south, eventually coming to form the water borders we know today, Floridians rejoice. Now relieved of Poseidon’s blanket, the spot where zillions of plankton lived and died became a super nutrient-rich strip of soil spanning the length of the deep south.

Fast forward a while, there are people in North America. Then more people arrive and mercilessly remove the ones that are already there. These new people start setting up… farms. Eventually, they come to learn that the farms along that fertile strip of land produce way more cotton than the farms outside of it. The farmers can make hella money, assuming they can find enough labor resources to grow and harvest the crop. That’s not a problem.

The farmers are in luck: there’s slavery! For very low prices, they can rip the native people of another continent from their homes, lives, and families, and put them to work doing foreign agricultural labor. The black belt, named for its rich, fertile black soil, becomes densely-populated by cotton plantations and the slaves that work them.

Fast forward again, there’s a war: the United States’s southern elite is paranoid as hell that President Abraham Lincoln is going to take away their slaves, so they create their own country (for unrelated reasons). Conflict ensues. It lasts a few years, but the “we love slavery” team loses, and the slaves are freed by proclamation.

So now there’s no more slavery, but the people who were slaves have been living in the south for a long time, many being the descendants of early-wave slaves who had first been trafficked over a century before. Acts outlawing the kidnapping of more slaves made it so none of the new freedmen and women had any connection to their ancestral homeland. While some attempts to “return” Black Americans to Africa found moderate success (resulting in the establishment of Liberia and more minor colonies), most of the freed former slaves had no choice but to remain where they were.

Over the following century and a half, some of the deep south’s Black population would depart in waves to the larger metropolises on the coasts and the industrial cities of the great lakes, but many would remain where they’d now put down roots of their own. In more recent years, descendants of some of the Black Americans who left would return to the region.

Today, most of the people who live along that fertile strip of ancient plankton soil are Black. In recent American political history, Black Americans tend to vote for the Democratic party, standing against most voting southerners, who have voted overwhelmingly in favor of Republican candidates since the Silent Majority and New South eras of the 1960s and 1970s.

If you pull up electoral maps from the past several decades, you can see the Black Belt clearly, a living relic of both paleontological marine biology and the enduring legacy of slavery in the United States. Worth noting, though, is that this Black Belt isn’t as cartographically evident before the late 1960s, when voter suppression by groups like the Ku Klux Klan and the governments of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia kept Black Americans from the polls. Civil Rights advances like the Voting Rights Act in the 1960s paved the way forward for better representation and less open murder.

The Black Belt’s name comes from its dark, fertile soil, but you’d be forgiven for thinking it’s the name of a region populated by Black people. Soil fertility is an abstract concept important to farmers and those who study agriculture. For the rest of us, the most notable feature of this region is its high proportion of Black Americans, their history, and their enduring impact on American politics.

Images

- 2016 Presidential Election by County by Ali Zifan for Wikipedia

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

- New 2000 black percent by Wikipedia user Citynoise

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license.

Read More

- How presidential elections are impacted by a 100 million year old coastline by Dr. Craig McLain for Deep Sea News, also published by the University of California – Santa Barbara Geography Department

- How US Presidential Elections Are Impacted By Geology by David Bressan for Forbes

- Obama’s Secret Weapon In The South: Small, Dead, But Still Kickin’ by Robert Krulwich for NPR