This is part three of the series “The Last Chogyal of Sikkim”. Read part one here.

On March 20, 1963, the daughter of two American aviators, raised to adulthood by a paid caretaker in a New York apartment, married the son of a Himalayan King and Queen who, at birth, was named a saint of the local Buddhist faith.

The two had announced their engagement in the summer of 1961 but agreed to delay the wedding by more than a year after Sikkimese astrologers declared 1962 “inauspicious”. In his book, Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom (the Bible of this series), author Andrew Duff entertains the idea that the declaration may have been an attempt by the country’s religious elite to sideline the marriage until the two got bored of each other. When that didn’t happen, the astrologers relented and identified 1963 as a less-than-awful year to get married.

The wedding is as much the melding of two separate universes as the marriage will be; the American delegation, populated in equal measure by diplomats and recent college graduates, mingles with an audience of South Asian monks, nobles, and politicians.

Hope herself had flown into Sikkim only a week before the wedding, this time without a made-up itinerary and boyfriend left stranded in Iran. She brought with her no fewer than twenty-six suitcases (somewhat understandable) and twelve umbrellas and parasols (insane).

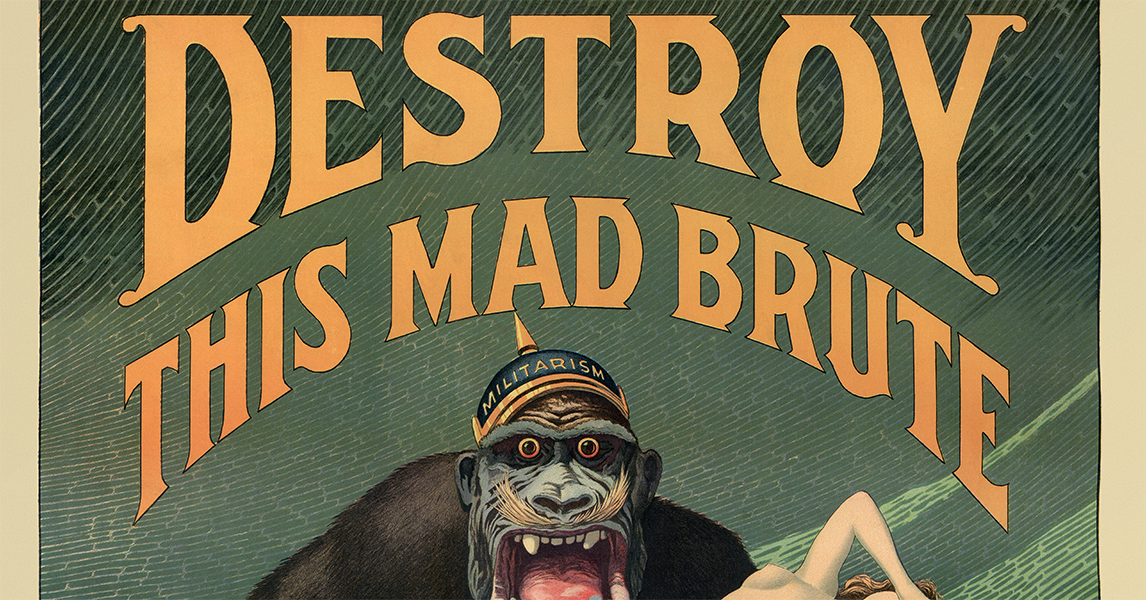

The celebration is a more unconventional affair than most of its Sikkimese attendees are used to. It eschews some cultural mainstays like the series of overtures wherein the bride’s family performatively tries to fight off the groom’s, the implication being that he’s stealing her away from them and that it’s up to them to stop him. In the end, they acquiesce, giving their child away in the name of unfortunate military superiority.

The Americans, not up to date on Himalayan Buddhist marriage customs, mess things up further. The American ambassador idly snacks on the sweet rice meant to be ceremonially offered to the Buddha. One of his countrymen sees the celebration of intercultural love as an unbeatable opportunity to try to convert a nation of heathens and spends the whole ceremony handing out Jesus literature.

Those in charge of planning the event hire a band from the Indian state of Goa to play the reception. Asked to add some American songs to the setlist, they choose “Dixie“, the Confederate anthem, which Hope even then recognizes as problematic.

The Opposition

The marriage feels under assault from the start, both from the King’s CIA-affiliated sisters (to whom Hope isn’t good enough) and from a sort of foil of Hope’s, a Belgian woman who also married into Sikkimese politics. Her husband has a name; it’s Lhendup Dorjee. But even the best sources I’ve found tend to stick with his title alone, the Himalayan honorific “Kazi”. It makes pieces about him sound like ghost stories, tales of a ruthless poltergeist circling the mountain kingdom waiting to strike. His wife, born Elisa-Maria Langford-Rae, becomes “The Kazini”.

The Kazini’s been criticizing the Chogyal and his family from afar for years, but she takes the wedding as an opportunity to strike in person. Sneaking into the hotel many of the guests are staying at, she tiptoes through the halls and stops to slip a poem she wrote under each door:

I am Hope, the New York Lepcha,

Oh, yes I really am

Though I’m marrying a Shamgyal

Don’t think I’m just a sham.

Her flair for subterfuge breathes no life into her writing; the poem’s corny as hell.

Shangri-La

The wedding ends and Hope officially begins her tenure as Gyalmo, the queen consort of Sikkim. In an interview with Time, she downplays the scale of splendor she lives in at the Sikkimese palace in Gangtok, calling it a “a 64-year-old, two-story white stucco building with five bedrooms and a tin roof.” She’s being modest. It’s no Versailles, but it’s still a big house.

The new Gyalmo takes some time to adjust, but she seems to take a genuine interest in the country and its welfare. Without much in the way of official responsibilities, she occupies her time with little projects to encourage outside investment and intrigue. Sometimes it’s convincing New York-based retailers to sell Sikkimese-made crafts and clothing. Other times it’s writing back and forth with a rich dude until he agrees to name one of his racehorses “Sikkim”. Some onlookers might balk at the use of her time, but she’s decades ahead of those nerds who put the dogecoin dog on a racecar.

Despite her active role in projecting the country’s face to the world, Hope’s image at the Sikkimese court is far from central. One theme that shows up in almost every article about her is that she’s impossibly quiet, choosing to whisper in rooms where everyone else is speaking normally. As deft as she becomes at promoting her image beyond Sikkim’s borders, Hope never quite masters the cultivation of her internal persona.

Accession

Palden’s father dies in 1964, immersing the country and court in an atmosphere of mourning. There’s an air of tension in the palace. The Queen plays some music too loudly on her record player and her husband has it destroyed.

The new Chogyal, who’d been fulfilling the duties of that role for a decade by now, takes the throne and its responsibilities but won’t be crowned until 1965. 1964 is, as you may imagine, an awfully inauspicious year.

The early years of Chogyal Palden Thondup Namgyal’s reign usher in an era of change; according to the New York Times, the new king promised to “banish poverty, ignorance and disease and to ”make Sikkim a paradise on earth.””. It’s a tall order. To his credit, the king’s reforms make a difference: the literacy rate rises from 25% to 40%, the number of children in schools quadruples, and average per capita income is up by 33%.

Of course, not all of the recent changes are positive. Sikkim remains reliant on Indian military aid, and increasing industrialization is changing the face of the once-pastoral nation. The Chogyal, who by now is traveling around in a Mercedes, laments a bygone era of going from town to town on foot, visiting each of the country’s major settlements at least once every three years. He still makes the visits, but they’re not the momentous, built-up-to affairs they used to be.

Long before his ascension, tremors of conflict had started to stir the Himalayan kingdom from just beyond its borders. The Chinese annexation of Tibet ends the plateau’s decades-long status as a British-bolstered buffer state between the communist world and the colonies of the west. The move rattles both India, which now shares a much longer border with a potential adversary, and Sikkim, where people live in fear of a Chinese advance into their own small country. The treaty the Chogyal brokered with India gave the New Delhi government responsibility over Sikkimese protection and military affairs, a responsibility they indulge in; the Indian military is everywhere in Sikkim.

With Chinese troops at the kingdom’s border and Indian soldiers within them, there’s a pervasive feeling of incoming danger in Sikkim, like the small kingdom’s been named the designated battlefield in a war yet to be fought.

The Chogyal’s first real reckoning with his own mortality comes when his cousin, the Prime Minister of neighboring Bhutan is assassinated. After retiring to the palace, The Gyalmo holds him through the night as he lies awake shaking.

The Indian military continues to drive discomfort, but the most potent source of internal tension in Sikkim is the ongoing political repression of the nation’s Nepali majority. The Chogyal sees the overwhelming numbers of Nepali citizens (most of whom are Hindu) as a threat to the country’s native Bhutia Lepcha people and their Buddhist culture. Acceding, in his mind, to their demands of representation, the Chogyal forms a parliamentary system in which seats are allocated equally to each of the nation’s three main ethnic groups. The Nepali are awarded one third of the seats, the same number as the Bhutia and Lepchas, despite making up nearly three quarters of the country’s population. The act gives them a voice while simultaneously being sure to guarantee that that voice can be easily overruled by the rest of the representatives.

The parliamentary apportionment isn’t an attack; if anything, it’s a passive aggressive denial of equitable representation. But at the same time as he’s concocting that plan, the Chogyal levies a series of separate assaults against the Nepali community, introducing laws meant to restrain further Nepali immigration and urge against Nepali intermarriage with members of the Bhutia and Lepcha minorities.

Each of these actions, indisputably anti-Nepali in effect, acts in the Chogyal’s mind to further his ultimate goal: a free Sikkim that remains true to its Buddhist cultural legacy. Pushing away the Nepalese is an attempt to advance the latter half of that goal, but the majority of his reign will be devoted to the former, the international recognition of free Sikkim. The pursuit of this goal will consume the Chogyal and, ultimately, his country.

The Chogyal’s ambitions and the Gyalmo’s jet-setting lifestyle coalesce and the two spend much of their time flying around the world on a variety of missions, both state and personal. As Hope visits friends and cares for the children, the Chogyal makes use of his time abroad to cultivate diplomatic connections, meeting with as many foreign royals and heads of state as possible. The Indian government takes these meetings personally, reminding the Chogyal that the treaty they both had signed gives India the responsibility of caring for Sikkim’s foreign relations. By meeting with kings, queens, and presidents personally, he’s cutting out the middleman. Undeterred, the Chogyal starts flying the Sikkimese flag alongside the Indian on his government-supplied car and formally readopts the title of Chogyal, replacing the India-favored Maharaj.

Sikkimese dreams of full independence are further complicated by the growing conflict between China and India. While neighboring Nepal’s position is bolstered by its neutrality and Bhutan’s is calcified by its formal recognition at the United Nations, Sikkim’s people and government see their state both as the would-be victim of a potential sequel to the Chinese annexation of Tibet and as China’s gateway to India. The Chinese supplement these fears by stationing thousands of soldiers on the Tibet-Sikkim border. They also don’t exactly calm the Chogyal’s anxieties when they send him a Christmas card featuring a picture of their successful hydrogen bomb explosion. It’s a little overkill; I try to stick to red-and-green hand grenades.

The Chogyal’s neighbors spend most of his reign in a confused, multipartisan nude wrestling match where allegiances shift on a dime. India’s Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, initially attempts to maintain positive relationships with both China and Pakistan, India’s medically-separated conjoined twin with whom the country shares a famed love-hate-hate-hate relationship, but things sour quickly. All three parties have conflicting claims to land in the Himalayas and Karakoram, the Central Asian mountain range that picks up where its more successful sibling left off. After cosplaying 1984‘s Eastasia, Eurasia, and Oceania for a while, the shattering of the Stalin-Mao BFF bracelet that is the Sino-Soviet Split causes everything to finally settle into place. China opens up to Nixon’s United States, and both maintain warm ties with Pakistan. Forced away from the cool kids, India cultivates friendships at the goth table with the Soviet Union and the future Bangladesh, now still the territory of East Pakistan.

It’s immersed in this atmosphere that the Chogyal is left fighting for a place for his country, desperately trying to squeeze through the sweaty grappling arms of these two burly collections of combatants. To him and his government, neither neighbor can look like a great option: on one hand, India refers to the Chinese troop surge as an attack on the Indo-Chinese border, which should be a massive red flag to every Sikkimese citizen whose search history leaves out the term “vore”. On the other, India’s rhetorical attack seems like nothing compared to the potential force of China’s real guns-and-bullets assault. Contemporary accounts reveal a thick fog of fear. The atmosphere leads the Gyalmo Hope to donate money to the Indian Prime Minister’s defense fund. Diplomatically, it’s a boneheaded maneuver, and the exact sort of thing that leads Sikkim’s cooler cousins, Nepal and Bhutan, to ignore her in the hall between Hindi and Mandarin class.

Tensions eventually cool and the Chinese pull back, but the whole affair has a lasting effect on the Chogyal and those around him. The country’s relationship with India, by now far beyond Friends with Benefits, continues to deepen, supported in no small part by the Chogyal’s warm friendship with Prime Minister Nehru. Nehru seems to hold a genuine affection for Sikkim that transcends his responsibilities as the country’s protector. He tells the Chogyal he’d like to retire there and regularly puts him at ease when concerns of growing Indian influence arise. Eventually, these conversations start to sink in and the Chogyal finally starts to feel confident. He’s a small player on the international stage, but he has a real friend. It won’t last. On May 27, 1964, Prime Minister Nehru suffers a fatal heart attack, leaving the Republic of India without its founding leader (and Sikkim without its ally) for the first time in seventeen years.

Next: The Chogyal’s Gambit