At the 1936 Summer Olympics, representatives of Haiti and Liechtenstein made a horrifying discovery: the two countries had the exact same flag.

At least, that’s how the story usually goes. It normally ends with both delegations returning home and each country promptly altering their flag to avoid further confusion and embarrassment.

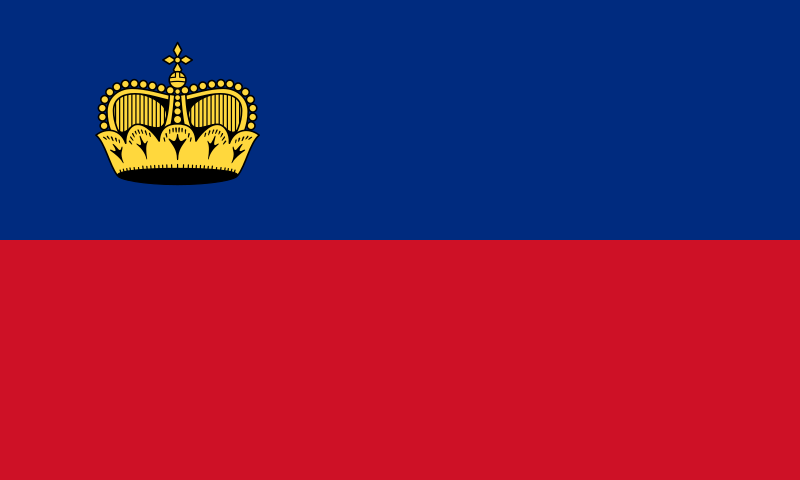

From what I can tell, the story’s mostly true. Liechtenstein, a tiny principality wedged between the Swiss and Austrian Alps, and Haiti, currently the most populous of the Caribbean island nations, were both at the 1936 Olympics, though Haiti’s sole athlete decided not to compete. Liechtenstein’s flag at the time was a simple bicolor: a band of blue atop a band of red. And Haiti’s flag at the time was the exact same, as long as you can forgive a grueling asterisk: it was the country’s civil flag.

The distinction between national and civil flags is somewhat esoteric and inconsistently enforced. In many countries, the two are one and the same. The easiest way to understand the distinction is by looking at the flag of a country like Spain. Most of the Spanish flag is relatively simple, a red-yellow-red triband. Its complexity comes from the element at its center-left, the national coat of arms. This is the flag most of us would recognize as the Spanish flag. But there is another variant. The one we know is the sole national flag used by the government of Spain, but citizens may empower themselves to use another: the Spanish civil flag. To draw that one, we follow the first step in designing the national flag, composing that red-yellow-red triband, and then… we stop. That’s it. That’s the civil flag of Spain.

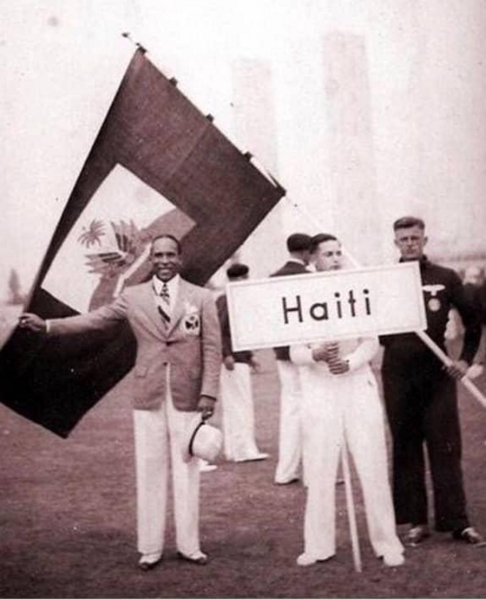

Most flags with a coat of arms on them have an accompanying “civil” variant without it. Similarly, many simple, color-first flags without emblems or coats of arms have a second, government variant, with the appropriate emblem or coat of arms embossed.When Haiti arrived at the 1936 Olympics, which, elephant in the room, were held in Berlin, surrounded by innumerable swastikas and Nazi flags, and commenced and overseen by Hitler, the Caribbean nation arrived with both the civil flag, a red and blue band incredibly similar to Liechtenstein’s, and a national flag, the same banner but with the national coat of arms sitting in the middle atop a white box.

From Liechtenstein’s perspective, the story detailing the country’s shock at recognizing they shared their flag with another nation an ocean and half a continent away and immediately acting to ameliorate the issue, that’s true. For the 1936 ceremony, the Liechtensteiner delegation received permission to fly their flag upside-down to distinguish it from Haiti’s, and by the following year the government had decreed that from 1937 on, the flag of Liechtenstein would bear a small crown in the upper corner near the hoist to forever do away with the threat of confusion.

It’s on the Haitian side of things that the story differs a little from the popular retelling. While the Liechtensteiner delegation elected to turn their flag upside-down, Haiti simply put away their civil flag and opted to use the national flag for the remainder of the games. The story here ends up being a little less interesting as the impact of the games on Haiti’s national identity is far less significant than on Liechtenstein’s. It’s true that after Berlin, Haiti continued using its national flag over its civil flag nearly everywhere, but this was also true before Berlin. The Haitian flag is and has been, in this way, just like the Spanish in that the national flag is far and away the flag most people associate with Haiti.

So, to summarize, it seems like the 1936 Summer Olympics did have an impact on the flags of both Liechtenstein and Haiti, but only in Liechtenstein was the event so substantial that it led the country to change the actual appearance of the flag. Haiti, in turn, merely decided to keep their civil flag in storage.

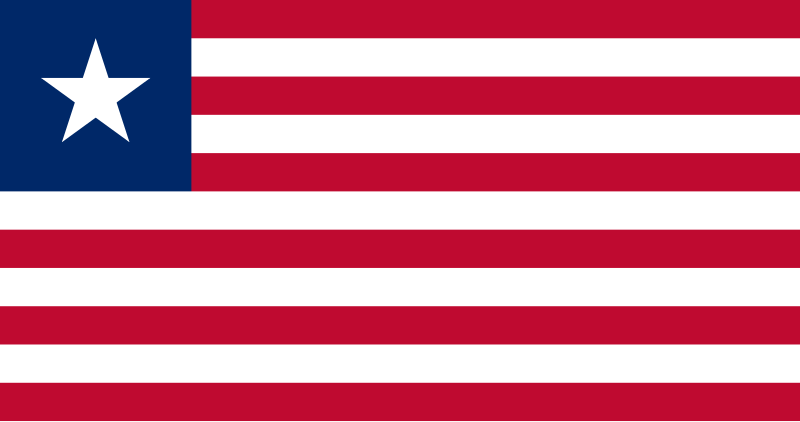

Even so, the story of two sovereign nations failing to recognize they’d chosen the same national regalia, especially well into the twentieth century, comes as a surprise. But… should it? Sure, some flags are complex, with varied and complicated elements making accidental replication difficult. The flag of the United States is one such example, incorporating a blue canton of fifty stars and a field of thirteen red-and-white stripes. The US flag is replete with symbolism, stark in color choice, and stands out against most national flags. But not all. Liberia and Malaysia both have flags that closely resemble Old Glory.

In Liberia’s case, the similarity has shared historical origins. The nation, about the size of Ohio and hugging Africa’s western coast, was founded by freed slaves and free Black Americans who chose or were otherwise coerced to return to Africa after obtaining their freedom. The capital city of Monrovia, named after U.S. President James Monroe, completes the connection.

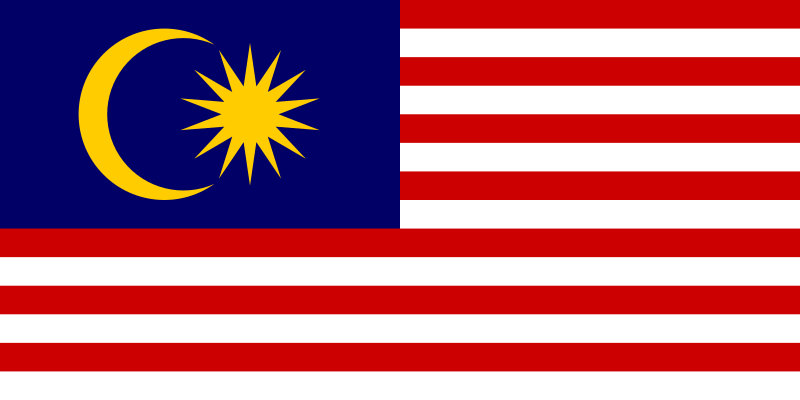

For Malaysia, the history stretches further back in a way that threatens to rob American patriots of their appreciation for so unique a banner as ours. The Malaysian flag features a field of fourteen red and white stripes beneath a blue canton, this time containing the yellow crescent of Islam and a single fourteen-pointed star. The stripes and star points alike represent the thirteen present states of Malaysia plus Singapore, the one that got away.

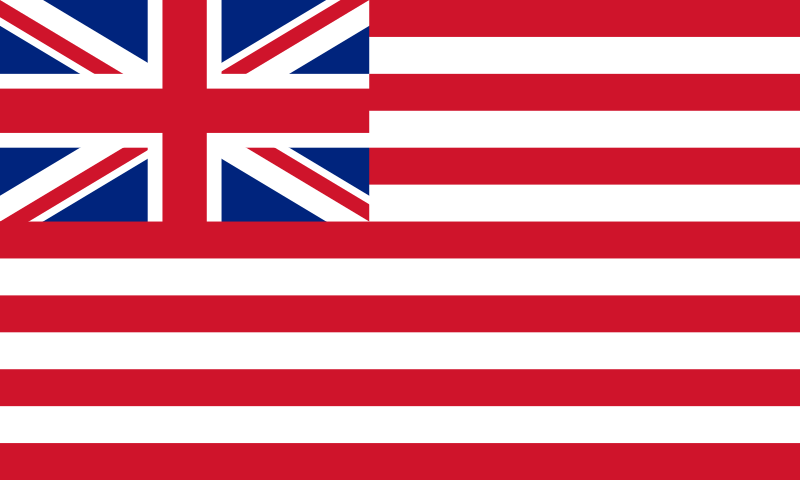

Malaysia, of course, doesn’t get all the credit for coming up with this design. But unlike Liberia, the credit surplus doesn’t swing back around to Washington. Instead, the United States and Malaysia might be examples of a sort of divergent flag evolution, both owing their red and white stripes and blue canton to the flag of the British East India Company. I stick to “might” because, despite the insane unlikelihood that the resemblance came about coincidentally, there’s limited evidence that the American flag was intentionally modeled after its megamonopoly quasi-corporate quasi-state predecessor.

Like the American, the birth of the Malaysian flag and its mix of elements is difficult to track, but it seems more likely that it took direct inspiration from the British East India Company, which would have been more active in Borneo and the Malay peninsula than in Philadelphia.

So, in fewer words: even a flag as unique and packed with design elements as ours can find itself beset by near-clones, but even a distant observer would be able to tell that the Liberian and Malaysian flags aren’t exactly like the American.

The same can’t be said for the African nations of Guinea and Rwanda, the flags of which were both born during Africa’s rush to freedom in the mid-twentieth century. Ruled until then by colonial overlords in Europe (Guinea by France and Rwanda under Belgium), both nations grasped the opportunity to forge new identities as they carved themselves from the colonial plaster holding them to their disparate neighbors and keyholders abroad.

To that end, both saw fit to rid themselves of the colonial flags that had for years flown above their centers of power and replace them with new banners that spoke to their identities as free African nations. In doing so, Guinea took notes from both Ghana and Ethiopia, the latter being one of the only African nations to fully escape colonial rule, incorporating what would become known as the pan-African colors: red, yellow, and green. (It’s worth noting here that there is a second set of “pan-African colors”, pioneered by Jamaican Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, that replace yellow with black. This article will continue to focus on the red, yellow, and green more popular on the continent itself.)

“Pan-African” suggests the whole continent inclusively, and so it’s unsurprising that Rwanda, too, would rather grab from the design choices of an African neighbor than a European monarch. Indeed, and true to their name, the pan-African colors continued to inspire flags on every end of the continent, from the Republic of the Congo in the south to Mali in the north.

Some of these flags are more complex, incorporating symbols or other colors alongside and atop the characteristic red, yellow, and green. Others are simpler. Rwanda and Guinea, as you might imagine, belong to the cohort of nations selecting that latter option and sticking with simplicity. And with so many new nations inspired to use these three colors, even the most ardent mix-and-matchers are going to eventually run into a permutations problem.

By all accounts, it was Guinea that introduced the flag first, in 1958. Rwanda followed three years later. And, to their credit, unlike Liechtenstein, that Alpine micronation that had to get invited to a party by Hitler before they noticed they’d copied someone else’s outfit, Rwanda noticed the similarity much sooner and modified their flag later that year. Where Liechtenstein chose a crown to represent that of their Prince, Rwanda chose the Latin letter “R”, to represent… Rwanda.

The elementary school teacher’s solution to identifying classmates with the same first name by appending an initial to one of them worked well enough for Rwanda that they kept the new flag for forty years, only changing it in 2001 in an effort to distance the country from the genocide that had ravaged it less than a decade before.

Even flags that differ visually can confound proud citizens of countries like Ireland and Côte d’Ivoire, who both fly vertical tricolors of green and orange separated by white but fundamentally disagree on which of the two colors comes first. For Ivorian vexillologists, orange represents the color of the country’s savanna landscape, white peace, and green hope. For Ireland, the white symbolizes peace, again a point the two can agree on, but the green and orange instead represent the country’s Catholic majority and Protestant minority. The Irish association with the color green is a tale as old as time. For more on why the Protestants tend be associated with orange, consider checking out my piece, Five Hundred Years of Orange.

Regardless, the mixed symbolism sometimes causes trouble for Côte d’Ivoire at the hands of anti-Irish agitators who end up inadvertently desecrating the flag of the country formerly known as the Ivory Coast.

The confusion can be brutal, but sometimes the similarity between the two comes in handy. When Ivorian sprinter Murielle Ahouré won the 60 meter sprint at the 2018 World Indoor Athletics Championships, there were no Ivorian flags nearby to adorn her on her lap of honor, so she instead borrowed the nearest Irish flag, turned it around, and continued on without anyone knowing any better. Until she told everyone.

Ripe for the same sort of confusion are the flags of Poland and Indonesia; both are simple bicolors, red on one side, white on the other. They differ, of course, in the sort of flag minutiae familiar to vexillology nerds: Indonesia’s flag is stitched to a 2:3 ratio of height to width, Poland’s proportions are 5:8. The hues of red are also slightly different. The biggest difference, of course, is that Indonesia flies red on the top, Poland on the bottom, so it’s easy to distinguish the Polish flag from the Indonesian at a distance.

Harder to distinguish are the Indonesian and Monegasque (belonging to Monaco) flags. There is, of course, the matter of different reds – Monaco’s is darker, like Poland’s – and of ratios, but those, again, are minute. The fact of the matter stands: any person taking an at-random trip around the world and crash landing in either Monaco, a tiny, urban, and extremely wealthy principality on the French riviera, or Indonesia, a massive, sprawling mega-archipelago of several huge and thousands of small islands, will have no idea which they’re in, assuming they come face to face with the national flag and immediately go blind to climate, wildlife, language, and culture.

Similarly, airborne explorers who crash land in either Chad, an African country straddling the Sahara that’s so hot its largest lake is disappearing, or Romania, a montane Eastern European nation half-covered in verdant forests and home to Dracula, will have no idea which is which, as the flags of these two nations, blue-yellow-red vertical tricolors, are almost exactly the same, right down to the dimensions. Only a slightly darker shade of blue saves Chad from a copyright strike.

As the cases of Rwanda and Guinea and Haiti and Liechtenstein teach us, it used to be that when you, being the proud and upstanding country that you are, arrived to a function only to find out another nation had picked out the same outfit that you had, one of you would do the right thing and change, or at least commit to consigning that particular look to closet purgatory when you get home from playing badminton for Hitler.

But Indonesia and Monaco, Chad and Romania, these countries have routinely worn the same dated, low-rise flag to every event for decades.

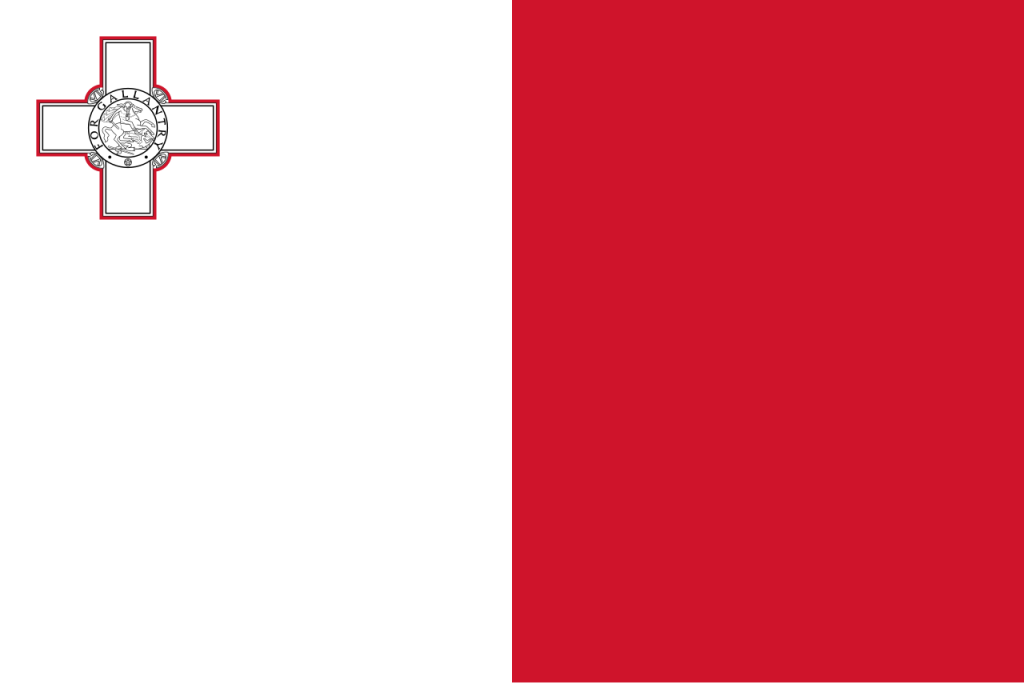

Showmanship isn’t what it used to be. Countries like Malta live by an old code. Their flag, like Liechtenstein’s, would be just another bicolor if not for one particular element. Even worse, the colors Malta’s chosen are red and white, making it identical in concept to the flags of Poland, Indonesia, and Monaco but this time rotated ninety degrees so the bands fly vertically. The stipulation, the asterisk elevating Monaco from a field of simple kin, has its origins in World War II, at the end of a two-year siege put on by friends of that mustachioed emcee who invited both Haiti and Liechtenstein to Berlin.

At the time, Malta was part of the United Kingdom, and for its gallantry in withstanding the siege, the King, George VI, awarded the embryonic Republic with the George Cross, one of the most prestigious military and civilian honors the crown can afford. But unlike the knights and soldiers who may be able to pin their medals to their chests, Malta was and remains an island. So instead, they added a visual representation of the cross to their flag, where it remains today.

So to us, moving from a time when vexillological confusion was enough for a country to change its whole identity to the present where the world is abound with near-identical banners, the change might seem unfortunate, boring, maybe ultimately meaningless. But to a country like Malta, the decline and its message are clear: chivalry is dead.

Read More

- Flag bearing: a potted history by Venetia Rainey for Reuters

- Flag and Coat of Arms from the Embassy of the Republic of Haiti in Washington, D.C.

- flag of Côte d’Ivoire by Whitney Smith for Encyclopedia Britannica

- flag of Liechtenstein by Whitney Smith for Encyclopedia Britannica

- flag of Malta by Whitney Smith for Encyclopedia Britannica

- flag of Malaysia by Whitney Smith for Encyclopedia Britannica

- Liechtenstein in the CIA World Factbook

- Liechtenstein change of flag from the International Society of Olympic Historians

- World Indoor Championships: Ivory Coast’s Ahoure celebrates 60m gold with Irish flag from BBC Sport