In March 2003, cafeterias serving the United States House of Representatives made an earth-shattering announcement: French fries were off the menu for good. Longtime fans of one of the nation’s favorite artery cloggers would have to content themselves with a new, homegrown alternative: freedom fries.

The central idea was the same: thin strips of potato fried in oil. The ingredients were the same. But the recipes? Yeah, also the same. The difference was that these fries weren’t French. They were freedom. In other words, the only thing separating freedom fries from their European progenitor was a veneer of performative political disgust.

Some backstory: A month before the Capitol’s french fries were forced to renounce their French citizenship, United States Secretary of State Colin Powell had addressed the United Nations, speaking at length about the nation of Iraq, its chemical weapons program, and its capacity to produce and use weapons of mass destruction. In retrospect, Powell’s speech, which used the phrase “weapons of mass destruction” 17 times was a sales pitch. The product? A second U.S.-led war in Asia. The stakes? The very fate of the world.

…if Iraq had weapons of mass destruction.

A month after Secretary Powell made his case, the United States hadn’t yet made war with the Hussein regime in Iraq. But many of the United States’s allies had preemptively locked arms, signing on to what President George W. Bush had named the Coalition of the Willing, the international superteam prepared to invade Iraq to save the world.

All the big names were set to perform. The United Kingdom was here. Australia, Japan, Italy. The international military powerhouse that is Slovakia. Missing from the list, however, was America’s oldest ally: France. The French president, Jacques Chirac, had refused to align his country with the coalition, arguing “Iraq does not represent an immediate threat that would justify an immediate war. France appeals to the responsibility of all to respect international law.”

Chirac’s position was in lockstep with the vast majority of his citizens, few of whom had been swayed by Bush’s call to arms.

The words of the French president would age well, as the American-led invasion and subsequent eight-year occupation would fail to locate any of the supposed weapons of mass destruction for which the war was ostensibly being waged.

Ultimately, thousands of coalition soldiers and tens of thousands of Iraqis would die in a conflict that saw the brutal dictator Saddam Hussein removed from power but sowed the seeds that would lead to the rise of the Islamic State, the invitation of al-Qaeda into Iraq, and a period of regional chaos and destabilization that echoes into the present.

At the time, though, Americans and their allies were riding a high of patriotism stemming in large part from the September 11 attacks a year and a half earlier.

It’s hard to draw a direct line between the Hussein regime in Iraq and the largely Saudi Arabian-led and Central Asian-housed terrorist organization that attacked New York, Washington, and Pennsylvanian agriculture in 2001. Anecdotally, having been a child growing up in middle America at the time of both of these wars, the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq felt largely inseparable. After September 11th, America had taken the villain label so easily applied to the terrorists that brought down the World Trade Center and spread it haphazardly across a definition of the “Middle East” that bled profusely over the actual cultural and geographical borders of the region.

It’s not difficult to find Americans who still believe that Afghanistan is a middle eastern country populated by Arabic-speaking ethnic Arabs.

This is all to illustrate that Iraq, in America, was not just an opportunity for the United States to flex its muscles and play world policeman, it was very much a continuation of America’s revenge plot against the wide scope of enemies who had breached its defenses.

So, when France, supposedly the United States’s oldest ally and a country whom Washington had (only begrudgingly) come to the aid of in two separate world wars, refused to participate in the invasion of a country on the basis that they might have had weapons that countries like North Korea were also undoubtedly at work developing, the American cultural response was sour.

So sour that in some bastions of particular patriotism, individual proud Americans like Neal Rowland, the owner of a Cubbie’s fast food chain restaurant in Beaufort, North Carolina, decided to do something about it. For folks like Rowland, the actions of the French people in refusing to take crusader roleplay a little too far were so egregious that they justified not only rebuke but also the erasure of all evidence of French influence on American culture, starting with the most prominent: the french fry.

At Rowland’s Cubbie’s, french fries had been consigned to oblivion, and in their place, freedom fries were born.

Does it bother me that Rowland could have grasped the opportunity to turn this into a “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” fight by joining on with underdog Belgium in defending its claim to be the one true inventor of the deep-fried treat we now freely attribute to its southern neighbor? Sure, of course it does.

But it’s not only there that Rowland’s creativity fails him. The idea to rid American culture of its vestiges of foreign influence in a time of war, it didn’t come to him in a dream. In interviews with journalists, Rowland was clear and proud to attribute his inspiration to a phenomenon from nearly a century before. With the world at war, another European adversary caught America’s eye. “Freedom fries” were a short-lived phenomenon that died years before the war they purported to support. But the anti-German crusade that appeared amid a much shorter, albeit much deadlier and more wide-ranging conflict, still bears its mark on American culture today, a century later.

Deutschamerikaner

“One century ago, German influence in the United States was more dominant than Hispanic influence is now.”

Erik Kirschbaum, Burning Beethoven

Asked by the United States Census to self-report their ancestry, the most common response Americans gave in 2020 was “Black or African American”. The third most common was “Mexican”. Between these, number two, at 12.3% of the American population, was “German”.

Modern America is replete with examples of Black and Mexican culture. Black America has been at the heart of American music, literature, and cuisine for centuries. Mexican heritage plays out in the same pattern but also in the pockets of Spanish that are spoken throughout not only those states that border Mexico but the broader United States, certainly every large city but also elsewhere wherever the distant sons and daughters of Mexico (and, of course, other Spanish-speaking countries) inhabit. Some of the people who populate these cultural enclaves are recent immigrants, having arrived within the past decade or two, but others are the children, grand-children, even great-grandchildren of those who crossed a border that looked different than the one newer immigrants cross today.

The point I’m making is that culture, and subculture, endures even against the eroding effect of time. Black culture could be an outlier, shaped by the unique and often tragic history of Black Americans, a people largely robbed of their disparate trans-African histories and forced to create a new shared history with people whose ancestors looked, talked, and acted differently but who were all, to their White neighbors and enslavers, unilaterally Black. Mexican culture, too, could be maintained by a constant flow of Spanish-speaking immigrants, without which enclaves may be tempted to turn over time to English.

But even ethnic groups populated almost exclusively by the descendants of immigrants from a century past retain some semblance of their original identity. 9.2% of Americans call themselves Irish. 4.8% of Americans label themselves Italian. The cultural heft of both of these labels remains strong even though Irish emigration to the United States peaked in the 1850s. Italian arrivals started and slowed later, but that tapering had begun around 1920, now over a century ago.

The vast majority of Americans proud to call themselves Irish or Italian were born and raised in the United States. Still, their cultures endure in them, having been passed down by those who came before.

Why, then, is German culture in America comparatively absent? Sure, Americans won’t balk at an Oktoberfest, though these are a relatively recent introduction to the American cultural repertoire. German influence bears its way into our lexicon in such terms as “kindergarten”, “wanderlust”, “zeitgeist”, and “angst”. The most common response to a sneeze, the most dignified of forceful bodily expulsions, is some flavor of “(God) bless you”, but coming up in second is the German “gesundheit.

German immigrants made up a greater proportion of the United States than and arrived around the same time as their Italian neighbors. In 1890, sixty percent of St. Louis’s residents were of German origin, according to writer Erik Kirschbaum in his book Burning Beethoven, a text I’ll reference throughout this piece. In Milwaukee, the percentage of occupants tracing their origins to Germany was even higher at seventy percent.

These specific examples may be outliers or arise from particularly dense communities of immigrants moving together from German-speaking Europe, but they’re far from alone. Throughout the greater midwest, Germans constituted by some margin the largest number of immigrants. By 1900, New York City housed the world’s second-largest German population after Berlin and more than a quarter of New York’s 3.4 million residents were either born in Germany or born to parents who had been born in Germany.

The influence of these German origins ran deep. German was the exclusive language spoken in many rural midwestern towns throughout the late 1800s. In Burning Beethoven, Kirschbaum writes about Irish immigrants to the United States who ended up learning German to better fit in with their local communities.

This is a far cry from today’s Midwestern United States, where finding any sign of lasting and meaningful German influence beyond an unending cascade of surnames bearing “sch” or the “ae”/”oe” scars of the umlauts that came before is more of a scavenger hunt.

Speculators might imagine that the cause of a precipitous decline in German pride and identity came on the heels of World War II, when a torrent of Nazi mega-atrocities changed the face of both Germany and the world. It’s not hard to imagine such a conflict affecting German-American culture the same way it affected the name “Adolf”.

But, in reality, it was the prequel to that conflict that put an end to German America, the original world war. Caused by the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s reaction to the assassination of their crown prince’s assassination at the hands of a Bosnian Serb, the war quickly ballooned out of control and came to involve nearly all of the world’s powers.

Austria had started the war and would bear perhaps the greatest cost: the total destruction of its empire. But Germany, who had joined the war in defense of its southern cousin, would come to be identified in the west as the aggressor and general antagonist of a convoluted conflict.

Today, American entry into the war against Germany and on the side of the allies is taken for granted, partially thanks to the easier moral flavor of the subsequent World War II. But at the outset of this first world war, American involvement was far from obvious.

For most Americans, entry into World War I was either inappropriate, against American ideals, or morally wrong. For many German Americans, war against Germany meant seeing their adoptive and birth parents at odds with one another. While some German-Americans lobbied to join the war on the side of Berlin, many more preferred to throw their weight behind the majority of their newfound countrymen in favoring neutrality.

And, for the first thirty-three months of the war, this majority of the American public got their way. As war exploded between the great powers of Europe, the United States maintained its comfortable seat on the distant sidelines beyond the Atlantic.

While some German-Americans continued to outwardly support their home country’s war effort in Europe, most remained focused on keeping their new country neutral, intent on avoiding the uncomfortable position of being torn between loyalty to the United States and fighting against their remaining friends and family back home.

But despite their efforts and those of neutrality-minded Americans in government and throughout the country, two events occurred in 1917 that propelled the United States inexorably toward the so-called Great War.

First, in January, the United States intercepted a diplomatic cable from Germany to Mexico in which German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman offered to help return the southwestern states lost to the United States in the Mexican-American War if Mexico would agree to join Germany in the United States declared war.

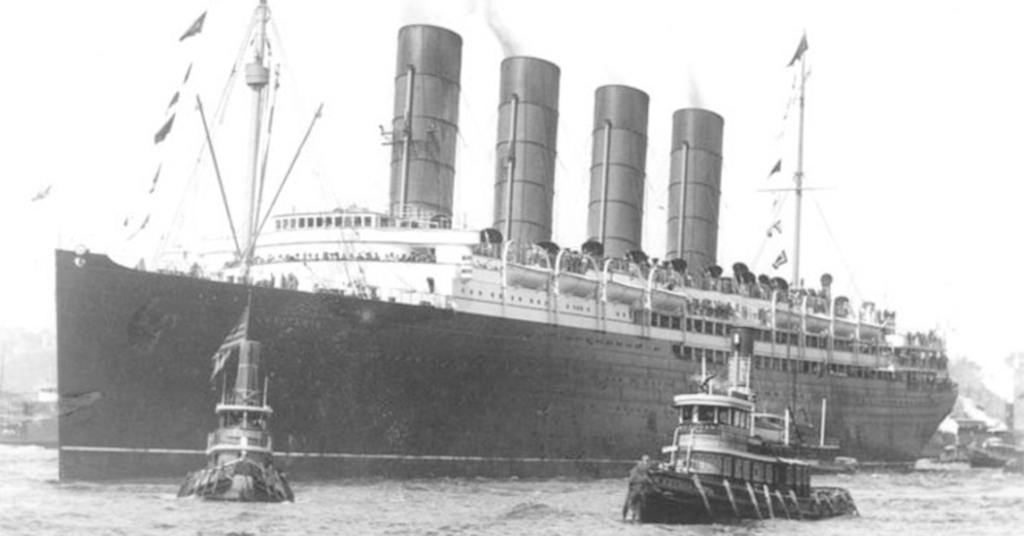

Second, less than a month later, Germany resumed its practice of unrestricted submarine warfare against all ships, military and merchant alike, in the North Sea. This practice had been interrupted in 1915 when a German U-Boat sank the RMS Lusitania, killing 1,197 people, 10% of whom were American. At the time, some German-American newspapers reported positively on the attack.

On April 6, congress formally declared war on Germany.

The Enemy Within

Overnight, America’s largest immigrant group went from just one of many occupants of the nationwide melting pot to subjects of national suspicion.

In Kentucky, after a number of horses died without explanation, a local judge publicly blamed the area’s German-American population.

Writing on the topic of German-Americans, former President Theodore Roosevelt opined, “They play the part of the traitors, pure and simple. The hyphen is incompatible with patriotism.”

The “hyphen” Roosevelt refers to here is the one that hangs out between “German” and “American” in “German-American”. The position of this great statesman of the republic would be imitated countless times in the year and years that followed: in the United States, there was no more room for someone who was anything other than purely American.

This is a sentiment not foreign to today’s observers of American cultural backlash. We remain quick to label those who come from elsewhere as enemies within. This was not the first time immigrants had been the victims of nativist scrutiny and it clearly wouldn’t be the last. But for German-Americans, this was their unique time in the spotlight.

California Representative Julius Kahn recommended this supposed traitorous activity be responded to with “a few prompt hangings”.

In light of both the declaration of war and their country’s sudden turn against them, German-Americans broadly responded with a turn of their own toward intense patriotism for their adoptive nation.

An editorial in the St. Paul Volkszeitung argued “No matter how great the suffering and mental agony that German-Americans would undergo, there can be no question about their loyalty to the stars and stripes.”

The German Catholic Union of Baltimore was one of many such unions whose members voted to commit their undivided loyalty to the United States. The leader of the German Veterans Alliance of North America declared that German-Americans, if called upon, would not hesitate to involve themselves in the war against Germany.

At the same time, some Germans were involved in Acts of sabotage against American industry long before the country’s entry into the war. The logic was that, despite being neutral, American factories were producing arms and war materiel to be bought by both sides; after the United Kingdom instituted a naval blockade of Germany and Austria, Germany’s ability to purchase and receive American armaments dropped precipitously. Thus, the Germans, left without their share of the overseas weapons market, felt they were better off sabotaging the otherwise-uninterrupted British access.

These acts of sabotage resulted not only in damage to property and industry but also in death. Boat bombings committed by Germans and German-aligned saboteurs often involved the placing of a timebomb on ocean liners that would explode while the ship was mid-voyage, resulting in its cargo and occupants both being lost at sea.

A German-American instigator successfully managed to set off a bomb at the U.S. Capitol Building and later shot the banker son of J.P. Morgan in the groin for his support of the British, French, and Russians against Germany.

Other attempts at sabotage were less successful. One American physician aligned with Germany attempted to conduct biological warfare against horses and was foiled only by his inability to conduct biological warfare against horses.

Representatives of Germany and her allies in the United States explicitly encouraged these acts of sabotage, successful or not. The Austrian ambassador to the United States was forced out of the country after declaring that any Austro-Hungarian citizens working in American factories would be found guilty of treason. German-American publications were split on the issue of his removal.

Franz von Papen, later one of the central figures responsible for Hitler’s rise to power, was at this time a modest German diplomat eventually expelled for more directly encouraging Germans in America to sabotage and destroy infrastructure.

These calls came to a head on July 30, 1916, at Black Tom Island in the New York Harbor. Of all of the ammunition sent from the United States to Europe to fuel the war, three quarters of the supply was packed at Black Tom. Knowing this, German agents snuck into a depot containing two million pounds of explosives and set a series of fires that were detected by the island’s nightwatchmen. These sentinels, also understanding the island’s payload and the futility of attempting to prevent what they viewed as inevitable, quickly escaped the ensuing blast.

The fires burned for two hours until, at 2 a.m., the ammunition ignited and created a colossal explosion powerful enough to be felt and heard as far away as Maryland and Connecticut. The blast, registering a 5.5 on the Richter scale, shattered windows up to dozens of miles away.

Erik Kirschbaum, author of Burning Beethoven, writes “At least seven people were killed and hundreds more injured in the worst terrorist attack to that point in the United States.”

The statue of liberty was hit with debris, and total damage topped $400 million in 2025 dollars.

The blast was not initially attributed to pro-German sabotage but instead first to an accidental fire and then to an Irish anti-British group.

Decades after this war and nearly a decade following the next, the government of West Germany would reach a settlement with the United States, agreeing to pay $50 million in reparations for the attack.

Pro-German acts of sabotage were on the rise in the United States, but so far these threats had been localized to the acts of individuals and not directly traceable to German leadership. This changed precipitously in early 1917 when the British intercepted a wire from Germany to Mexico now known as the Zimmermann telegram.

Zimmerman to Mexico: wyd?

Expecting that the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in the North Sea would trigger war with the United States, the German Empire’s leadership hoped they could ease the burden of a transatlantic conflict by enrolling overseas allies to help in their future fight against America.

To that end, the German foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a coded message to the German ambassador to Mexico offering to that country that, if Mexico agreed to declare war on the United States alongside Germany, Germany would help guarantee that Mexico reclaim the southwestern U.S. states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

A century out, it’s hard to imagine a deal of this sort bearing fruit, and it’s hard to imagine a state like Texas being anything but American (except maybe Texan). Indeed, even at the time, it seemed like a tall order, and there’s no evidence that Germany had any immediate plans to offer much more than symbolic support to potential ally Mexico.

But in 1917, the Mexican-American War, that 21-month conflict that netted America much of its southwest from Texas to California, was less than seventy years out. There were plenty of Mexicans alive at the time who had been born in a Mexico that stretched up toward Oregon, and many more whose fathers had fought for those borders and lost.

Indeed, while it’s tempting to imagine today that America’s southern neighbor had nothing but positive intentions and refused this invitation to treachery as soon as it arrived, the President of Mexico at the time, Venustiano Carranza, put a commission together to determine how realistic a project such a land reclamation may be. In the end, the verdict was clear: even with German support, a Mexico already racked by its own ongoing civil war would have a near impossible time conquering and placating a substantial swath of its northern neighbor’s territory.

Mexico would not be joining World War I. But the United States had made up its mind.

America at War

On April 6th, 1917, the United States congress declared war on the German Empire, with a similar declaration against its principal ally Austria-Hungary coming eight months later.

Soon after the onset of the war, life for members of one of the United States’s largest and most prominent ethnic groups changed considerably. More than six thousand Germans were arrested as “alien enemies”. Of these, two thousand were placed in American concentration camps.

An additional 2,200 German merchant sailors were interned at a single camp built by the lowest bidder, a hotel owner operating out of the 650 person-strong Hot Springs, North Carolina.

Kirschbaum writes that conditions in these camps were better than those experienced by the Japanese-Americans interned during World War II, but prisoners were still subject to forced labor and cramped dwellings.

The vast majority of German-Americans and Americans of German descent were free to continue their lives as (relatively) normal for the duration of the war, another stark difference from the 120,000 Japanese-Americans removed from their homes two and a half decades later. But while only some two thousand German-Americans were kept in the camps, around 250,000 German-born men who still held European citizenships were required to register their addresses and employment information at their local post offices.

German citizens residing in the United States were legally prohibited from entering Washington, D.C. and the Panama Canal Zone and were similarly disallowed from boarding airships, balloons, airplanes, and most boats.

With the war came an explosion of paranoia regarding the sort of episodes of pro-German sabotage explored earlier in this text. Reports of small glass particles in food and milk, though disproven, quickly became the “razor blades in Halloween candy” of the early 1900s.

It was in this atmosphere of official repression and fear that Americans began pushing back against German language and culture in the United States. In January 1918, the “Loyalty League of American Schools” was organized to identify “disloyal teachers” and order their removal from the classroom. In the League’s eyes, any teacher who refused to lead their students in the pledge of allegiance qualified for disloyalty.

When the United States Commissioner of Education argued that studying German would still be worthwhile even if Germany forever remained an enemy of the United States, he faced calls to resign. Three New York schoolteachers were fired for expressing feelings of neutrality regarding the war.

These academic reprisals began having an effect. In 1917, 1,400 students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison were enrolled in German courses. Two years later, that number had fallen by 87%.

When the South Dakota Council of Defense demanded that all state schools and universities immediately stop teaching German, seventy-five students broke into a high school in Yankton, South Dakota, grabbed all the German books they could find, and flung them into the Missouri River.

In May 1918, the governor of Iowa, William Harding, issued the Babel Proclamation, similarly forbidding Iowa schools from teaching their classes in languages other than English, but also going as far as banning the use of any non-English language in public.

When an Iowan pastor complained that half of his decades-old congregation wouldn’t be able to understand his sermons if he were forbidden from giving them in the community’s native Norwegian, the governor responded “there is no use in anyone wasting his time praying in languages other than English. God is listening only to the English tongue.” Governor Harding went on to be censured by his state’s House of Representatives for accepting $5,000 to pardon a man who had raped a 17-year-old girl.

The South Dakota ban was similarly wide-reaching for Germans, preventing the use of the language not only in state schools but also private and church-associated academic environments, as well as church meetings and public gatherings. A later order named German “the enemy’s language” and prohibited its use in all cases except those “of extreme emergency”. At the time, approximately 22% of South Dakota’s 584,000 people spoke mainly German.

Laws like these were passed throughout the Midwest. In Iowa, there were cases of people being fined hundreds of dollars for being caught speaking German on the phone. Still, these official punishments were far less harsh than those imposed by local mobs and vigilantes. Reports that ministers were tarred and feathered by local nativists for continuing to speak German are difficult to verify, but ethnic Germans elsewhere in the country (across thirteen states by Kirschbaum’s count) were forced to endure that punishment, including a Catholic priest in Texas and a farmer in Minnesota, two of the most recent Americans to be afforded that torture.

All of this was a devastating blow to the countless towns wherein German was the primary language of family, religious, and civic life. Americans who had safely spoken only German to each other for their entire lives, who had never learned and never needed to learn English, were forcibly silenced.

Liberty Measles

On April 13, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order establishing the Committee on Public Information (CPI), a state propaganda office headed by journalist George Creel. The official portfolio of the committee was to drum up support for the war, but it also took upon itself the job of organizing the variegated anti-German language campaigns under its own umbrella.

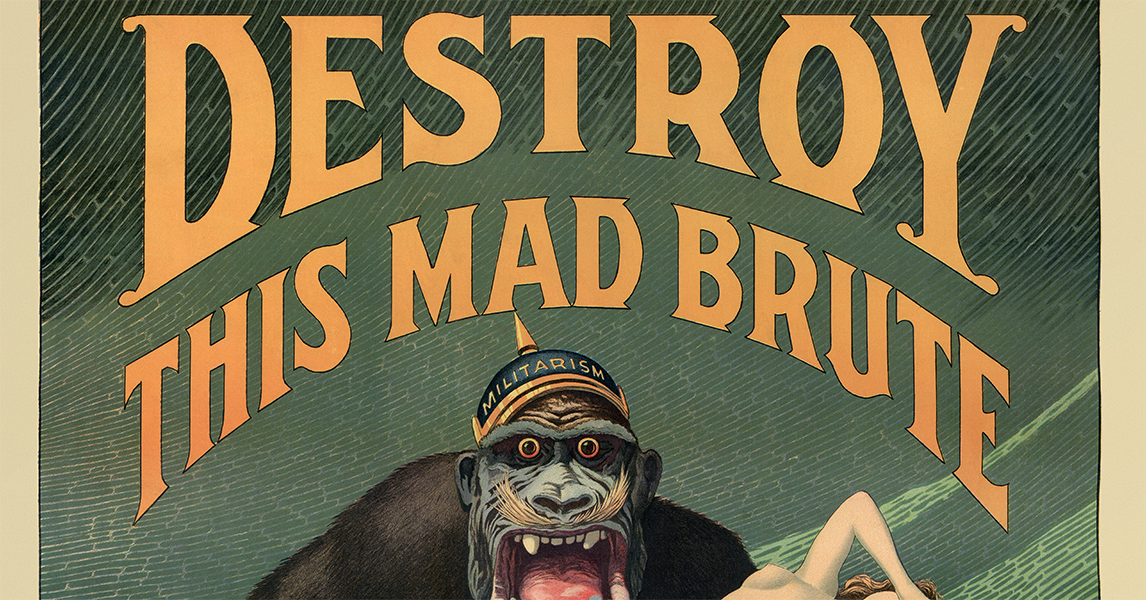

Much as the United States of eighty-some years later saw a campaign to attack the French by renaming French fries, the Creel Committee endeavored to erase the legacy of German influence on the English language by amending even more nouns.

Sources aren’t entirely clear on which of these changes came directly from CPI and which were more grassroots efforts at German erasure, but the two came to work in tandem, with anti-German cultural attitudes bolstering the work of a government agency tasked with reinforcing those attitudes.

“Sauerkraut” became “liberty cabbage”. “Hamburgers”, named after the nefarious German city of Hamburg, became “liberty sandwiches” or “liberty steaks”. Animals weren’t exempted; Dachshunds became (can you guess??) “Liberty hounds” or “liberty pups”. This change may be one of the least whimsical and most unfortunately necessary, as, in one of this story’s grimmer turns, stories of dogs being taken and killed for the crime of bearing a German breed name rise in tandem with the surge of anti-German sentiment.

Once started, these prescriptivists errant were unstoppable in their voracious editing of the English language. Hamburgers and dachshunds, these would have been beloved by millions, a love inconsistent with the required hate for the German menace. This meshes with other changes like renaming the Bismarck pastry the “American Beauty”. But this emotional valencing of German-derived nouns mattered little to those responsible for the cleansing of our national tongues. “German measles”, an infectious disease causing full-body rashes, also had to be changed to (what else?) “liberty measles”, guaranteeing that American children could only be infected by the most patriotic of pathogens.

Evidence of German influence was scraped from companies nationwide. The Germania Life Insurance Company became “National Guardian Life Insurance”, and the Germania Life Insurance Building in Saint Paul, Minnesota was renamed the Guardian Building. It bore that name until the 1970s, when it was destroyed to make space for a new apartment development.

Germantown, Nebraska received a new identity alongside towns in Iowa, Michigan, Indiana, Missouri, and Texas. Street names were changed in Cincinnati and New Orleans. Wisconsin passed a law in 1917 that allowed renaming any town or city by simple majority vote in order to ease the process of cleansing that state of its heavy German influence. Kirschbaum also writes that Wisconsin “made it much easier for residents to Americanize their family names and even provided new legislation enabling minors to change their names on their own.”

Burning Beethoven

The eyes of these censors and patriots fell next on music, particularly the works of prominent German and Austrian composers like Ludwig van Beethoven (dead for most of a century) and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (outlived by George Washington).

One German symphony conductor, Frederick Stock, was arrested and kept in an internment camp as a “dangerous enemy alien” alongside twenty-nine members of his orchestra.

Another conductor, Otto Scharf, was found to be staying in a hotel in Omaha by proud paint-wielding patriots who took to the brave act of painting his hotel yellow. When the owner attempted in vain to stop them, they painted him as well. The police later arrived and arrested Scharf, the conductor, for “disturbing the peace”.

For many German-Americans, there was no correct way to live during these years of war. When a California businessman of German Jewish background produced The Spirit of ‘76, a film about the American revolutionary war, he received a ten-year prison sentence for depicting British redcoat soldiers attacking American civilians, supposedly a crime against the present war effort now that the British and Americans were fighting on the same side.

Identität

In The Tragedy of German America, John Hagwood writes “No longer were the modern Germans able to think of themselves as Americans with a German flavor, or as German-Americans, or as Germans who were born in America. Germans were undesirable aliens, and in 1917 they became enemy aliens”.

By the 2020 census, 19.1% of Americans reported German ancestry for a total just shy of 45 million people. Yet fewer than one million people reported the ability to speak German.

By comparison, of the almost 8 million French Americans,more than 14% could speak French. This, like Spanish, is an outlier. For the descendants of Italian and Dutch immigrants speaking Italian and Dutch respectively, the numbers are just north of 3%. At 1.9%, German doesn’t feel that far off. But German was an outlier too. Isolated farming communities from Pennsylvania to the Rocky Mountains had been founded around the use of the German language and the continued propagation of German culture as unifying elements. Some groups of European immigrants, like Italians and the Irish, also tended to settle in more urban areas where communities (at least those readily identified as “white”) may blend together more readily, compared to the largely rural and separate communities of the midwest.

Recall that at one point, 22% of South Dakotans spoke German as their first language. South Dakota was and is still a small state and is hardly representative of the country as a whole, but academic data cues us further into the decline. Before the first world war, 25% of American high school students were learning German. Just four years after the war’s end, that number had dropped to 0.6%.

In 1910, at least 9.5% of Americans, or 8.8 million people, spoke German natively, a number likely tamed by its failure to include second-generation speakers. Today, only ten percent of that number, 847,700 Americans, can still speak German, despite the number of German Americans skyrocketing.

German immigration to the United States had largely tapered from the boom of the mid-19th century by the turn of the 20th, so many of these new German-Americans were second- or third-generation, born American citizens, many of whom would have been native English speakers. It’s easy to attribute the decline in German speaking to a natural attrition toward the dominant culture.

But the data gives us direct evidence to the contrary. Kirschbaum writes that in 1910 there were 488 German-language newspapers in circulation in the United States. Just ten years later, the number had dropped to 152. In another ten, by 1930, the number had fallen to just ten.

The effect isn’t attributable to a downturn in the newspaper industry. In the same period that German-language publications collapsed, newspapers catering to other languages, such as Spanish, Italian, and Yiddish, expanded their readerships.

While German-language American newspapers were in freefall, those published abroad had difficulty making it to their stateside audiences thanks to the wartime naval blockade, effectively cutting many communities off from information presented in their native language.

In addition, two laws signed by President Wilson after American entry in the war authorized the United States postmaster general to take a heavy hand against the German press. German-American newspapers were expected to publish an English-language version to prove they didn’t contain any anti-American messaging. Newspapers that displayed sufficient patriotism could be exempted from this and other restrictions, but smaller papers that struggled to fund the required translation operation were forced to shut down.

While German-language American newspapers were in freefall, those published abroad had difficulty making it to their stateside audiences thanks to the wartime naval blockade, effectively cutting many communities off from information presented in their native language.

In addition, two laws signed by President Wilson after American entry in the war authorized the postmaster general to take a heavy hand against the German press. German-American newspapers were expected to publish an English-language version to prove they didn’t contain any anti-American messaging. Newspapers that displayed sufficient patriotism could be exempted from this and other restrictions, but smaller papers that struggled to fund the required translation operation were forced to shut down operations.

But for many Americans whipped up by the nationalist fervor of wartime, the pivot came too little too late. Already suspicious of the German element surrounding them at home, Americans applied a far greater degree of skepticism and expectation toward the German-language press than they had to other periodicals. Stories from these papers that failed to cast German victories in Europe in a negative light or attempted to continue reporting the war in neutral, journalistic terms, were equated by Americans to outward support for the German Empire.

Writers and editors of English-language newspapers were also incentivized to shore up their own readerships by destroying their foreign-language competitors. By the end of 1917, some papers were subject to government raids.

Impact

The first amendment to the United States constitution guarantees American citizens freedom of speech and freedom of the press. To the millions of German-speaking Americans living all over the country in the mid-to-late 1910s, America, once the land of freedom and opportunity, presented a different promise: freedom of speech and press alike for any language but theirs. Just as restrictions, raids, and civil condemnation caused the rapid decline of the German-language newspaper industry, laws regulating civilian speech spread throughout the states where most German immigrants had made their homes.

In the span of just a few years, German-Americans went from a largely ignored and unmolested community to the at-large personae non gratae of their adoptive nation. The language that had allowed them to greet their neighbors and buy eggs from the corner store just a month before had become grounds for arrest.

Almost all of the crimes, sanctions, and actions committed against German-Americans that I’ve listed here occurred across just two or three years starting in 1917. By the time the 1920s were well underway in the United States, most Americans had forgotten their passionate rage against the nation of the Kaiser. They’d remember again in just two short decades when another German tyrant expressed an interest in war with the United States (and, conveniently, the world), but these negative attitudes would disappear even more quickly after this second world war, when burgeoning conflict with the communist east made cooperation with a newly-minted West Germany attractive.

American skepticism, distrust, and hate for its German minority fell almost as quickly as it rose, with most Americans forgetting the vitriolic feelings they’d held just years before. But the German-American community, irreparably damaged by the lasting impact of laws restricting their freedom of speech and the actions of a nationwide community set on limiting the influence of their shared language, would never be able to so easily shake off their injuries. For them, the impact was permanent.

Language

The individual creation of terms such as “liberty measles”, “liberty dogs”, and “liberty sausage” were each actions inspired by a temporary conflict. “Freedom fries” existed, similarly, as a sort of flash in the cultural pan: here today, gone tomorrow, mocked forever.

But these terms, collected, are similar in that they provide the silliest pieces of evidence for two separate eras of American patriotism, times when not insignificant numbers of Americans rose up against enemies whose borders transcended the extent of the threat posed by those trapped within.

These names are ridiculous and worthy of the laughs they inspire. The deaths and damage they accompany are less so.

You’d be hard pressed to find more than a couple of holdout restaurants proudly serving freedom fries today. Liberty cabbage has to be even harder to find. But there’s no shortage of new words flowing out from political movements new and old. Restaurants serving both of these dishes meant to send a message, just as an administration renaming the Gulf of Mexico the “Gulf of America” and restoring the name “Mount McKinley” to honor a president who lived and died thousands of miles away from that mountain bearing his name meant to send a message.

Actions like these feel small, meaningless, silly. And, in isolation, they are. But their consideration, their enactment, their support, no matter how limited, occur in tandem with larger political forces and attitudes. What we say is a window into how we think. And those who speak the language of cultural destruction are liable to put it to action.

Read More

- 20 years ago, the U.S. warned of Iraq’s alleged ‘weapons of mass destruction’ by Jack Mitchell for NPR

- America’s War on Language by Dennis Baron at the University of Illinois

- Burning Beethoven by Erik Kirschbaum

- During World War I, U.S. Government Propaganda Erased German Culture by Robert Siegel and Art Silverman for NPR

- French fries back on House menu from BBC News

- German Immigrants During World War I from Iowa PBS

- Legal Restrictions on Foreign Languages in the Great Plains States, 1917-1923 by Frederick C. Luebke at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln

- Liberty Measles at West Point from The New York Times

- N.C. Restaurant Sells “Freedom Fries” from My Plainview

- Professor Emeritus wins award for research on the response to WWI-era German language restrictions by Judith Zwolak for the University of South Dakota

Images

- Bremen Pershing Covington 2021.jpg (edited) by Wikipedia contributor Antony-22

- Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International