In the video game series Civilization, fans take a few things for granted: battles last hundreds of years, George Washington exited his mother’s womb in the Stone Age, and Mahatma Gandhi, the peace-preaching founder of modern India, loves launching nukes.

Civilization is a 4X strategy game where players take the reins of one of history’s prominent nations and attempt to rule well enough to achieve victory through military might, cultural diffusion, scientific achievement, economic power, diplomatic consensus, or religious conversion.

In their quest for victory, players choose historical figures, usually political leaders, to act as their avatars for the duration of each (very long) game. Each entry in the Civilization series since the original Sid Meier’s Civilization launched in September 1991 has allowed players to play against each other in organized multiplayer matches, but the colossal duration of each game means that most Civ players choose to play instead against AI bot opponents.

When you or I embody a leader like George Washington or Cleopatra, Civilization lets us run wild, making our own, often anachronistic, decisions in an attempt to secure victory for our people. Each leader and civilization comes with its own set of perks and abilities, but destiny is generally player-made.

Other leaders, however, are not so laissez-faire. The game’s developers generally push each leader’s AI in a direction inspired by their approach to leadership in real life. When faced with a choice between different types of government, you can opt toward communism or fascism, but AI George Washington will go for Democracy. There’s nothing stopping your version of Genghis Khan from avoiding war and spending his time building opera houses, but AI Genghis knows no alternative to blood and conquest.

These in-built attitudes have led players to build associations with leaders that transcend the bounds of a single game and make their way into the shared consciousness of online forums: Sumerian leader Gilgamesh is a great ally (and the archetypical bro), Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang is an awful enemy for anyone trying to build world wonders, and Mahatma Gandhi loves building and using nuclear weapons.

Porbandarppenheimer

The story of Gandhi’s nuke-happy attitude is perhaps Civilization’s most prominent and most enduring meme. Every Civilization player worth their salt has heard and repeated it.

The supposed origin of the legend goes back, either to the original Civilization or its sequel, Civilization II. In each game, online commenters will regale you, leaders’ AI engines were driven by a series of character-defining values. These values, stored as numerical digits along a scale rendered in game from 1 to 10 or 1 to 12 depending on version of the story, can determine how likely civs are to prioritize science, who they seek to befriend, and how itchy they are to go to war.

It’s that last value, aggression, that we’re interested in here. The story goes that Gandhi, being modeled after the real, peace-loving Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, had the game’s lowest aggression level, one out of ten. This meant that if Gandhi spawned as a leader in one of your games, he was incredibly unlikely to act aggressively and declare war unprovoked.

However, in Civilization, AI is not static in its behavior. As the game proceeds, unlocking different technology or pursuing different government policies can alter how AI enemies act. A previously-friendly leader who becomes a fascist autocrat late in life may grow more likely to declare war as a consequence of their choices. And a past-life warmongerer who chooses the path of democracy might find their passion for battle blunted by a newfound love for their fellow man.

It was the latter option, a switch to democracy, that changed everything for the Gandhi of internet lore. The story goes that AI bots who choose Democracy over alternative options have their aggression level decreased by two points. Despite being displayed as a one-to-ten or one-to-twelve axis, the data in the story is numerically stored in the game’s files as a 256-bit unsigned integer, meaning aggression actually exists on a spectrum from 0 to 255. And because Gandhi’s default value of 1 (or, in 256-bit terms, 0) is as low as it can possibly go, Democracy should theoretically have no effect.

…but, due to a programming quirk, a democratic Gandhi’s decreased aggression level didn’t stay put at its lowest value and instead overflowed, the game’s internal logic assuming that one minus two was neither zero nor negative one, but the in-system maximum of two hundred and fifty-five. As a result, Gandhi went from being Civilization’s most peaceful, war-averse leader to becoming by far its most violent warmonger.

Players who coexisted with Gandhi long enough for him to develop democracy were thus introduced to a colleague who would spend most of the six thousand-year game as a largely benevolent neighbor and before making a sudden turn toward psychopathic super-aggression. And because modern democracy only becomes an option fairly late in the game, this heel turn toward violence would often be accompanied by the development of nuclear weapons, paving the way to absolute, world-ending destruction from the modern founder of the doctrine of nonviolent resistance.

Gandhi’s nuke-happiness in the historical annals of the first two Civilization games was apparently the result of an overflow error, but this overflow error inspired such iconic memes and stories that developers hard-coded it into future games: Gandhi would, true to life, choose peace where able, but once nukes were on the table, all bets were off. And it all came, as the story goes, from a simple glitch.

…or did it?

This is how the story went for well over a decade online. It was an explanation that spread rapidly not only through the Civilization fandom, but through online gaming as a whole. Friends of mine who have never finished a game of Civ have gleefully shared the story of Gandhi and his love for nuclear war.

But the story, as it turns out, is not true. The Gandhi of Civilization yore was never uniquely prone to using nuclear bombs. Testimony from devs in the past several years, including from the game’s original designer, Sid Meier, has debunked the story. In a video interview with People Make Games, Civilization II lead designer, Bryan Reynolds explained that the supposed one-to-ten aggression scale was really a much more compact one-to-three, and that Gandhi was not an outlier, sharing his lowest aggression status with a third of the game’s leaders.

Similarly, in his memoir, original designer Sid Meier reported that values in the first Civilization game were signed and thus not prone to overflow errors. As such, Gandhi’s likelihood to seek and utilize nuclear power was no higher than his peers.

The true origin for the story of Gandhi’s nuke happiness is hard to place, potentially lost to the space beyond the event horizon of the early internet. But even though the technical explanation, the wordy path through integer overflow I made you read through in order to get here, is all made up, I think the story behind it probably grew a little more organically.

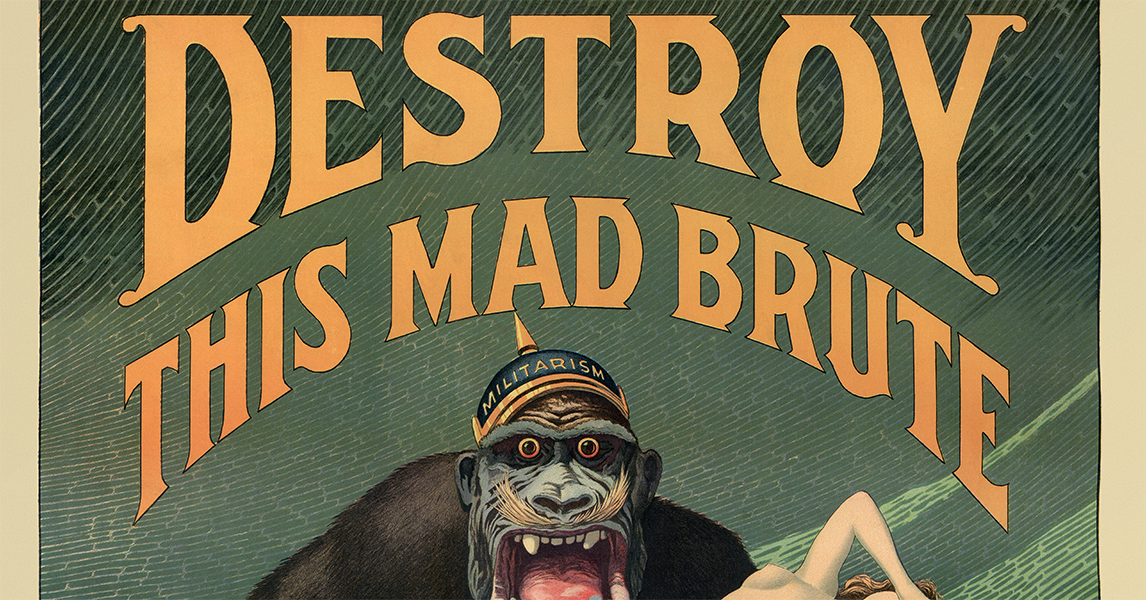

The use of nuclear weapons in Civilization games is, by nature, jarring. It’s surprising when any leader launches a weapon that has, knock on wood, only been used twice in all of history, both times by the same guy and against the same enemy. But once the initial shock of being on the receiving end of a catastrophic nuclear strike wears off, the identity of the person on the other end of the launch is less important. It may have been Otto von Bismarck who pressed the big red button in your most recent game, but it could just as well have been Augustus Caesar or Alexander the Great.

But Gandhi? The guy who famously used civil disobedience and nonviolent demonstration to defeat British rule? From him, a nuclear attack is particularly shocking and, notably, memorable.

Civilization games are so long and so enthralling that their stories become little microhistories embedded in the minds of their players. Worlds originally populated only by the distant capital cities of a handful of historical leaders give way to expansive competing empires that abut one another along wide, contentious borders. Neighbors become allies or enemies, developing game-long micro-reputations for duplicity, strength, or failure depending both on the AI contender in particular and the circumstances of the game.

In one match, Napoleon Bonaparte may be separated from the player by an ocean and thus be rendered comparatively harmless, while the next may see him spawn as the player’s closest neighbor with contention over nearby resources giving him all the reason he needs to become a game-long adversary. In that scenario, the player may have no choice but to regale friends with the story of epic, hundred year-long conflicts with the French Marshall.

Similarly, anyone who spends thousands of in-game years cooperating or contending with a war-averse Gandhi will naturally be shocked when the circumstances of the game and an impending victory push this otherwise pacifistic leader to war. And, because an in-built interest in science leads Gandhi to naturally develop the technology for nuclear warheads, he’ll deploy them at will just as readily as other cautious leaders like Abraham Lincoln.

It may be, then, that despite being no more likely than other leaders to pursue nuclear conflict, Gandhi’s nuclear strikes feel more meaningful because of who the figure he really was. In the end, this story is, like my history of Civilization victories, less science and more culture.

More

- Did Nuclear Gandhi Ever Really Happen in Civilization? by People Make Games

- Sid Meier’s Memoir!: A Life in Computer Games by Sid Meier