Nutmeg and cinnamon, a hint of pine, and the ferrous aroma of an ongoing bloodbath. It’s December. We all know what that means: we’re suiting up for yuletide combat. It’s fightin’ season, baby. The politically correct are trying to kill Christmas. Secular America is trying to steal Christmas. Big Christianity doesn’t want you to know that they already stole Christmas from the pagans. Everything’s so disjointed. What’s up with “Happy Holidays”? What the fuck is Kwanzaa? What’s happening to the Christmas I knew and loved? It’s moving, growing, changing. But not any more than it always has.

On its face, Christmas is a Christian holiday celebrating the birth of that religion’s main character, Jesus Christ. For most practicing western Christians, it’s the most important holiday in the cultural canon. But for much of the religion’s early history, it wasn’t. For the first two or three hundred years, Jesus didn’t even have an official birthday; the Bible didn’t think it was worth mentioning (you can only put so many words in a book and things start looking pretty full after a hundred pages of begetting and begotting).

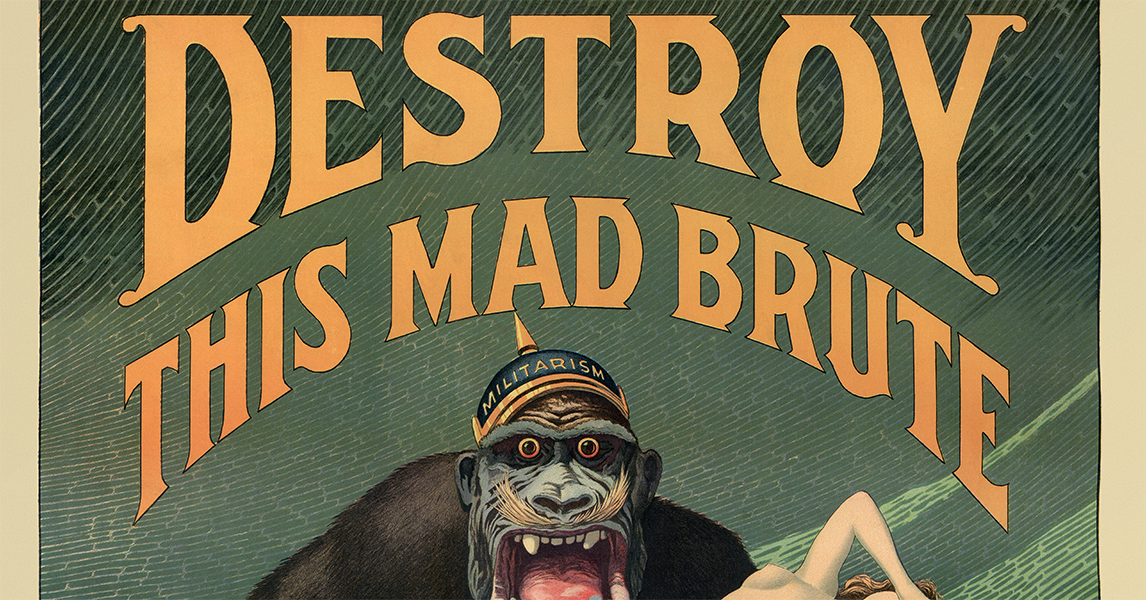

When the biblical protagonist was finally allowed his very own birthday party, the contemporary Christian bigwigs charged with scheduling it decided on December 25th. Their reasoning is complex and obfuscated by time (my preferred method of writing “idk why”). Theologians point to a variety of arguments, but my favorite explanation is that the church was looking to take advantage of existing real estate opportunities; in the Europe of the early common era, you couldn’t get hotter than December; December was fun as fuck. Those responsible for the raucous revelry? It’s time to meet the pagans.

“Pagan” is a catch-all term for followers of a variety of non-Abrahamic religious traditions popular in Europe during the first half of the first millennium. Pagans didn’t call themselves pagans. They probably had their own cool names. Christians saved time and called them all pagans. These groups were diverse and probably celebrated a wide variety of holidays, most of which are as lost to history as their very fun names. One thing we do know is that they loved themselves a solstice and that many held big celebrations around winter’s bummer version, the shortest day of the year. Celtic druids celebrated by lighting candles and decorating their homes with mistletoe and holly. Yule-celebrating Germans burned a (yule) log. Traditions like these would later be adopted by Christians as their religion supplanted the smaller native faiths.

But to say Christmas is nothing but a rebranded Yule, that the Christians stole all of their traditions from their Celtic and Germanic contemporaries, is simply inaccurate. They also stole from the Romans. The polytheistic people of the Roman Empire celebrated Saturnalia, a festival honoring Saturn, the god of (among myriad other things, greedy as the gods are) wealth and agriculture. Saturnalia was a bonkers, raucous time where celebrants threw out social norms and reveled in the name of liberty, obliging themselves by drinking, eating, gambling to excess, and regarding slaves as social equals (cRaZy! Y’all must have been drunk as fuck for this one). Amid the overindulgence and general excess, Roman citizens somehow found time to exchange gifts. There was also room in the several-day celebration of all things Saturn for one of his cousin deities, Sol Invictus, Roman god of the sun. Some two hundred years after the birth of Jesus, the reigning Roman emperor declared that December 25th was to be celebrated as Sol Invictus’s birthday. When the Christian church in Rome was searching for a date for their own birthday celebration, they just happened to land on that same day, easing the cultural inheritance process. Bad news, partygoers, there’s no Sol Invictus here. Unrelated, have you heard of Jesus?

In essence, Saturnalia was closer to a frat party than the more peaceful family affair Christmas is today. But the transition is less stark and immediate than you might assume. In the 1600s, Puritans in England and the United States banned Christmas celebrations for being rowdy 12-day-long affairs involving massive feasts and heavy consumption of alcohol for those who could afford it. Roman traditions were still echoing a thousand years after the empire’s fall. It wasn’t until this puritanical pivot that these long-held customs were widely and officially called into question.

With all that Christians borrowed permanently stole from their neighbors, I’ve made it easy so far to write Christmas off as a rebranded pagan tradition, a ChristMart version of Yule, but that’s not entirely accurate. The season has gained, but so too has it tragically lost. Gone are the days of commemorating the gods with live animal sacrifice. Left behind are traditions like parading a horse skeleton around town and making townsfolk welcome it into their houses.

Everything else Christmas that wasn’t transplanted directly from ancient Germanic, Celtic, and Roman traditions was added later, much of it in the latter half of the second millennium and from the bottom-up, often starting as hyper-specific local traditions that ballooned in popularity with time and exposure.

Santa Claus, for example, started as a real 4th century saint who lived in modern day Turkey. Appropriately the patron saint of children, Nicholas also served as the patron of sailors, making him an icon to the Vikings who dug up his body and distributed pieces of it throughout Europe. As his name spread, locals combined his own legend with that of local lore figures like Odin, a Norse god with a big ol’ beard and flying horse. Over time, the Dutch Sinterklaas made his way to the United States, where American accents and a couple of popular stories turned him into the Santa we know today. (If this paragraph went too quickly for you, consider listening to it in 17-minute podcast form here.)

Today’s gift exchanges may have grown in part from the holiday’s Saturnalia roots, but some sources suggest the tradition may have also sidled over from nearby New Year’s Day during the Victorian Era. The British Queen was attested to have exchanged presents with her family members at Christmas, giving one child a suit of armor (sick) and her husband a miniature portrait of her when she was seven years old (weird).

The earlier, pre-Young Victoria gift exchanges contributed to the Puritans’ distaste toward Christmas. A day spent sharing presents with friends and family was a day not entirely devoted to religious pursuits. Modern evidence has shown that giving gifts makes both givers and recipients significantly happier and helps us bond with those closest to us. Medieval evidence suggested it sucked hard and distracted us from God.

Some holiday traditions are entirely home-grown, with little background in religion or culture. Advent calendars, for example, were probably invented by a Bavarian mom tired of her kids asking her how many days were left until Christmas. I’ve written before about my family tradition of hiding a plastic pickle in the Christmas tree. Some sources tie it back to old German rituals, but that’s a lie (a fun one). There’s no prescription for these traditions, no religious mandate, no cultural responsibility — those who partake do so because it’s fun.

Humans (at least those of us in the northern hemisphere) seem drawn, somewhat naturally, to the solstice when cold nights are longest. It’s a persistent form of human magic that turns what could easily be the worst part of the year into, for many, the best. Did secular celebrants take from Christian tradition? Did early Christians steal from the pagans? Maybe. Probably. But I don’t think the season owes everything to anyone. The Celts wanted to celebrate. Germans, Romans, and Christians wanted the same, to share in the revelry.

For most of its early history, Christianity’s most important celebration was Easter. It was the already-breathing festive season that drew meaning to Christmas. Today, that almost inexplicable allure is still pulling. Most Jewish people consider Yom Kippur to be the most important Jewish liturgical celebration, but it’s Hanukkah that gets all the cultural attention. The story of Judaism is one of expulsion, abuse, and sacrifice. Hanukkah is about a lamp that burned a little too long. It’d be a blip on the Jewish radar if not for its proximity to the holiday season. When American professor Maulana Karenga created Kwanzaa in 1966 to celebrate African heritage and culture, he placed it squarely within the Christmas season, on purpose, to give his audience of Black Americans a reason to celebrate. That there should be celebration seemed obvious.

I wrote two years ago about the Japanese tradition of having Kentucky Fried Chicken for Christmas. Local KFCs take reservations months out and offer expensive Christmas baskets to patrons. This one makes the news because it’s weird, but more common traditions, like carols and Christmas trees, have also made the leap across the Pacific, gaining surprise popularity in a predominantly Shinto, Buddhist, and nonreligious country.

The holiday season is everywhere. In the United States, 65% of adults identify as Christian, but 90% of adults celebrate Christmas in some way. Religious affiliation is on the decline, but observation of Christmas is relatively stable. If trends from 2017 have continued, fewer than half of American adults will attend a Christmas church service this year.

I can’t blame Christians for finding these statistics alarming. They’re indicative of change, but it’s clear that if there is an ongoing war, Christmas is not one of the belligerents. It’s doing fine.

One of my favorite things about the Christmas season is how natural it feels. People, bound by no rules, under no obligation to participate, choose to. Sure, you may feel a responsibility to take part in reciprocal gift giving or family functions, but no one’s checking your house for mistletoe. You can’t get arrested for telling a kid Santa Claus isn’t real. But we abide because it’s fun. And when it’s not fun, we improvise.

I love Christmas. To me, no other holiday comes close. In a way, I’m the perfect audience for the “war on Christmas” narrative. But a world where shopkeepers don’t have to say “Merry Christmas” doesn’t scare me (52% of Americans agree). If you want people to enjoy your party, you don’t force everyone on your block to come — you throw a less shitty party (a skill I hope to have one day).

This season’s magic is in its persistence and its composition — traditions built over thousands of years, filtered through time. It’s been claimed by Roman emperors, pagan druids, and Christian hierarchs, but none of them owned it. You can establish a holiday, mandate its observation by members of your state or your flock. With enough authority, you can make them sing, dance, slaughter a goat on a ceremonial altar. But you can’t make them enjoy it. You can’t make them eagerly await opening presents on Christmas morning, picking out and setting up the tree, sharing cards and cookies with friends and family. That’s up to the people.

Maybe your Christmas is all of those things. Maybe it’s none of them. Maybe you’re one of the ≈50% of Americans who plan on attending church on December 25th. Maybe faith is an integral part of the holiday season for you, and maybe you love it. Or maybe you’re more like me, an outsider to religion who’s questioned my love for a holiday ostensibly not made for me. The beauty of the season is that it’s for everyone who wants to join in. Whatever dressings you cover it with, the core remains the same: a time for us to draw nearer those closest to us, to find joy in tradition, but also to forge it anew.

So who stole Christmas? The non-believers from the Christians? The Christians from the pagans? The pagans from whomever they were inevitably inspired by? I don’t think it was any of them. The season wasn’t theirs to begin with. In a way, it belongs to all of us, but in a more real way, if you’ll allow me to wax sappy as fuck, it belongs to you. So drink all the egg nog you want (or don’t, because it tastes like paint); sing all of the classics (or stick instead to nightcore and baby metal); and gather for a traditional Christmas dinner (or a video game marathon). Celebrate how you want with the people you want near you. The Romans made this season their own. So did the Celts, and the Germans, the creators of Christmas, Hanukkah, and Kwanzaa. Now it’s your turn. Give it a shot.

Or don’t. I’m not Santa.

Read More

- Christmas by Hans J. Hillerbrand for Encyclopedia Britannica

- How Christmas has evolved over centuries by Erin Blakemore for National Geographic

- In defense of secular Christmas by Michelle Garcia for Vox

- The Magical History Of Yule, The Pagan Winter Solstice Celebration from Huffpost

- The Origins of Christmas: Pagan Rites, Drunken Revels and More by Eve Watling for Newsweek