Remember when emoji were novel? When you might have judged someone (or been judged) for the inclusion of a cute little picture at the end of a message in the otherwise-very-serious medium of text communication? Now, if we’re not fluent in their proliferation, most of us are so used to them as to not be surprised by their quirks. We know that a trio of crying laughing emojis is an automatic induction into the comedy hall of fame, we know what the peach emoji really means, and most importantly, we know that a swirl of human feces has a face. And it’s pretty happy.

But there’s a war going on. By “war”, of course, I mean “brief, muted verbal disagreement” and by “going on” I mean “it happened three years ago on the internet”. All the same, as disagreements go, this one was… one of them. The instigator? The Frowning Poop Emoji.

Let’s start at the beginning.

The responsibility for the creation and maintenance of emoji falls at the doorstep of the Unicode Consortium, a collection of decision-makers populated mostly by tech companies, but with a few bizarre exceptions. Most publications graze over this part, but I think it’s interesting.

The Consortium’s website divides its membership between Voting Members and Associate Members. The “Voting Members” category includes companies like Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft, but also the University of California-Berkeley and the Indian Government. Those last two are considered “Institutional Members”, alongside the Governments of Bangladesh and Tamil Nadu, an Indian state with a unique linguistic history.

The Consortium’s eleven “Full Voting Members” also include Oracle, Netflix, Chinese technological giant Huawei, and… the Omani Ministry of Endowments and Religious Affairs. Twitter is relegated to the Associate Members category, an esteem it shares with Amazon and Tinder (no, for real).

Together, the Consortium gathers regularly to vote on which emojis make it into their standard and which don’t. It’s a job that wasn’t always theirs, but today, it’s one that’s taking up more and more time.

Back when the internet was fresh and new, text was sloppy. In order to display individual letters simply and not require users to load entire images for each one, early developers created a system of encoded language that assigned each letter a numerical value and loaded the visual depiction of the letter based on this number. Today, this is how text on the internet (and in texting and elsewhere on computers) works; every character you type is actually a set of numbers that tells the software you’re using which letter to load in its place.

When this system first came about, though, each piece of software or font had its own system of encoding, which made the internet generally not fun to wander. A word or sentence in one font or on one program could be copied and pasted into another and appear as nonsensical garbage.

This mess of copying and pasting still happens sometimes today, but it’s pretty rare, and when it does occur, it’s usually obscure characters appearing as boxes or a punctuation mark turning into a question mark or unrelated, accented letter. The reason we see less of it is the advent of Unicode.

Unicode was founded in 1987 with the express goal of creating a code for written languages that was, in their words, “universal, uniform, and unique”. Hence the “uni“ in Unicode. Uniuniunicode was taken.

Since 1987, most of Unicode’s work has gone into pulling letters, characters, and symbols from languages around the world into their unified code. Their success is the reason we see so few mysterious rectangles on our screens today compared to the rectangle-rife past that existed just ten years ago. And that’s just about all they did, exceptions including wingdings and an absurd number of arrows.

Everything changed for Unicode in 2010, but the journey that led us there starts ten years earlier. Emoji as we know them were invented by programmer Shigetaku Kurita while he worked at Japanese phone provider NTT DoCoMo. Originally, emoji were 12 pixel by 12 pixel images designed to convey information quickly between DoCoMo phone users. The initial set of 176 icons included weather-related images like a sun, rain, and a snowman, travel-related cars, trains, and buses, and a few fun inclusions like hearts, moon phases, and astrological signs.

With time, emoji exploded in popularity in Japan, and soon, other carriers began offering their own emoji. Not long after this, problems started surfacing. Just as fonts and software with uniquely-encoded letters had trouble displaying text typed elsewhere, emoji sent from one carrier to another were liable to be presented differently. On a good day, a smile might turn into an empty rectangle. On another, a solemn frown becomes an eggplant 😥.

Even if consequences weren’t that dire, the situation was confusing at best. Even today, the lack of messaging and communications parity between iOS and Android is nothing short of absolutely infuriating. Anti-Android bias is the real discrimination of the 21st–actually, let’s roll that back and move on.

In fairness, it was Apple who led the charge in bringing emoji to the United States by including an emoji keyboard on its iPhones in 2011. Before that, it was a team of Apple engineers who officially submitted 625 emoji for inclusion in the Unicode standard. And, in fairness, Android didn’t hop on the rapidly-approaching Emoji Train until 2013, which was two years later.

Having officially adopted the previously-limited emoji into their system, the Unicode Consortium had just taken on the responsibility for the management of emoji as a whole. Any new contenders to the existing supply would have to go through them.

Of course, the Consortium didn’t invent emoji, much like they didn’t invent any of the languages they’d conscripted into their universal code (except Ancient Sumerian – I won’t explain), they merely adopted them. As such, the soon-to-be universal set of faces and figures came with all the flaws built into them by the small teams of Japanese creators that birthed them. There are some cultural oddities and inconsistent inclusions, like “Man in Business Suit Levitating🕴️” and all of these: 〽️💸🎏🎍

A lot of this comes with the territory of the system having been designed for a singularly-Japanese audience, which is fair. But a global system meant to be usable by all opens the door to a few more concerns, namely representation. Many of the original stock of emoji were gender-neutral and racially-ambiguous yellow smiley faces, but those that were neither gender-neutral nor racially-ambiguous tended to be white dudes, and that can be a problem when there are people using your product who aren’t white dudes.

Over the next decade, the Unicode Consortium would gradually bring their set of icons up to speed, adding options for skin tone variation and hair color alongside different emojis for male and female users as well as a more culturally-inclusive array of foods, locations, symbols, and religious garb.

It took a while to update everything completely because the Unicode Consortium accepts suggestions in the form of formal submissions. Anyone can suggest a new emoji, but for it to be accepted, the Consortium requires a substantial level of detail. The Emoji should be easily usable, distinct, not covered by an existing emoji, and described in such a way as to limit confusion. Also, emojis cannot depict brands or individual people and should not depict ongoing trends that may die out soon (still waiting on my Harlem Shake Emoji proposal from last year).

For more on this process of emoji suggestion and acceptance, I recommend the 99 Percent Invisible episode Person in Lotus Position, which follows the journey of prospective emoji from idea to inclusion on phones around the world.

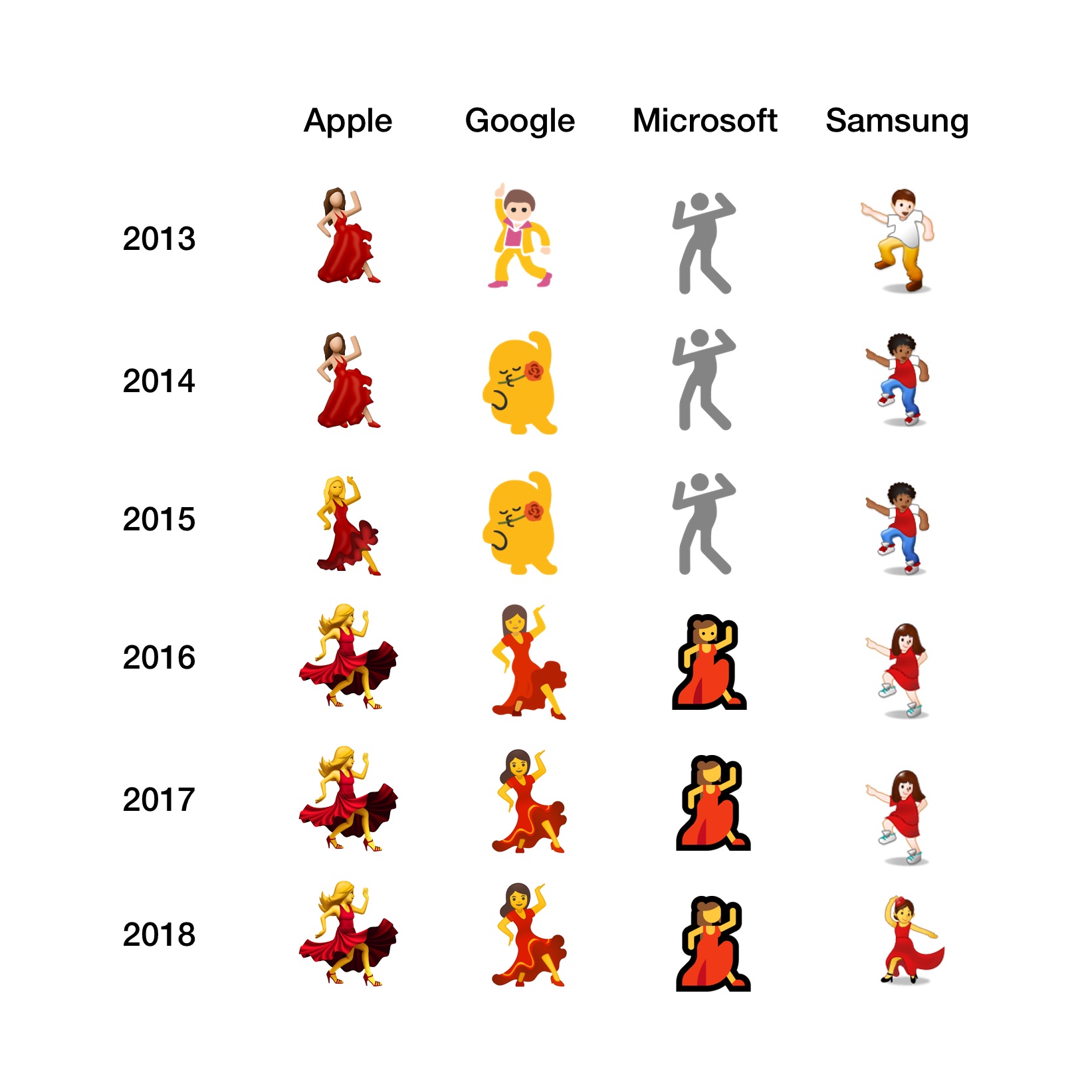

While Unicode’s emoji repertoire ensures that the idea of each emoji is universal, though, it doesn’t do anything for the actual appearance of each one. Just like different fonts take unicode text and give it a unique appearance, phone companies and app developers take Unicode’s descriptions and interpret them their own way. This is why, if you used emoji before 2018 and had friends with Apple, Android, and Samsung (the bad boy of the Android ecosystem) phones, you probably came to terms with a decent amount of confusion.

Perhaps most notably, for years, Apple’s interpretation of the “beaming face with smiling eyes” emoji looked more like a grimace than a smile. Similarly, each take on the “dancer” emoji differed significantly, between Apple’s salsa-inspired woman in a red dress, Google’s Saturday Night Fever aesthetic, and Samsung’s rapid-fire and diverse array of children. Over time, in this case, Apple’s interpretation of the “dancer” won out, owing to the perceived importance of the character’s particular appearance in how the emoji itself was being used. Unicode’s behind-the-screen description was “dancer”, but the practical application of the icon was “woman in a red dance dancing”.

Individual Images: Apple, Google, Microsoft, Samsung

Rarely, it’s initial divergence that leads to eventual convergence. At some point in the past decade, all the major emoji keyboard designers had come to agree that the “pistol” emoji should be depicted as a classical revolver. Then, in 2016, amid action in response to gun violence in the United States, Apple replaced its standing revolver design with a water gun. Adaptation was slow, but over the next two years, the rest of the big boys acquiesced, effectively eliminating the revolver from the emoji lineup.

That brings us to another case of depiction overruling Unicode intent, and the whole point of this piece. You’ve been awfully patient. Let’s talk about the poop emoji.

The poop emoji, or, Pile of Poo, to use its legal name, was first introduced to Unicode in 2010. Like many of its brethren in the Emoji 1.0 release, Pile of Poo had a history predating Unicode’s adoption of emoji at large, being grandfathered in alongside its more conventional kin.

The popularity of Pile of Poo shouldn’t be particularly surprising to most of us. If you’re surprised why people might want to share cartoon images of cartoon defecate, you might benefit from a visit to any first grade classroom in the world. Actually, don’t do that. You can’t go around asking kids about shit. Everything’s so PC now.

Regardless, fans and casual observers both may be quick to note that, much like dancer didn’t do enough to describe the appearance of a woman dancing in a red dress, Pile of Poo doesn’t quite get at why the star of this show has a face and emotion. Nothing in the description prescribes the face, and yet, reliably, it’s there.

The mystical origins of Pile of Poo’s smile remain a mystery to me, but it’s clear that, on iOS, it was there from the start. Meanwhile, earlier emoji designs from most other major providers stuck to a more traditional depiction of feces sans face. Google preferred swarming flies and stink lines until 2015, and Microsoft kept its poop traditionally unvisaged until August of 2016. Samsung’s Pile of Poo had a set of cute cartoon eyes long ago, but it didn’t earn a mouth until 2018. Now, though, all the major multinational tech megacorporations agree: the poop should be smiling.

Like the dancer and smile before it, the Pile of Poo is an example of emoji changing to fit its most widely accepted use. A smiling swirl of cartoon poo conveys a sense of humor and whimsy. A swarm of flies surrounding a pile of shit is a threat. So providers adapted, leaving users with one question: What if we don’t want the poop to smile?

Changing the minds of the remaining witholders of whimsical dook meant easier clarity across platforms for groups whose members already had access to the smiling poop, but just like the Android users deprived of a visual depiction 1970s John Travolta, fans of the disgusting poop emoji were left without reprise. Uses for this original depiction, such as… online fertilizer sales and Catalonians getting into the holiday spirit were flushed down the toilet.

Anything related to the newly minted product of the human colon must, by nature of the system, be displayed through a silly lens. But sometimes shit is shitty, so a mystery hero somewhere came up with a solution: Frowning Pile of Poo. Pile of Poo‘s lesser twin could be used to depict anything he could, but through a negative lens. The proposal was well-received and made it onto the shortlist for the next Unicode version. Then came the critics.

Among the most notable of these voices against the professional depiction of sad poop were Consortium members Michael Everson and Andrew West. In his memo, Everson writes “Will we have a CRYING PILE OF POO next? PILE OF POO WITH TONGUE STICKING OUT? PILE OF POO WITH QUESTION MARKS FOR EYES? PILE OF POO WITH KARAOKE MIC? Will we have to encode a neutral FACELESS PILE OF POO?”

The canon is that he’s screaming every time he types in all caps. FACELESS PILE OF POO.

I think we could go further, though. I say we bring back the option to add flies and stink lines to each of the aforementioned potential emojis. Pile of Poo with Karaoke Mic with Flies and Stink Lines could be used to indicate that someone is really bad at Karaoke, for example, whereas Pile of Poo with Karaoke Mic with Stink Lines but no Flies could indicate that they’re really bad at Karaoke, but they’re also not a big fan of bugs, and you respect that.

Everson’s memo also included the jarring assertion that “organic waste isn’t cute”. Kawaii composters of the world, are y’all hearing this?

West’s memo was much the same, reading “I personally think that changing PILE OF POO to a de facto SMILING PILE OF POO was wrong, but adding F|FROWNING PILE OF POO as a counterpart is even worse. If this is accepted then there will be no neutral, expressionless PILE OF POO, so at least a PILE OF POO WITH NO FACE would be required to be encoded to restore some balance”.

Y’all, I really don’t see what the big deal is. I say we go for it, but why stop at Pile of Poo with no Face? I’m drafting my proposal right now for Pile of Poo WITH Face, but It’s Turned Around So You Can’t Really Tell. Introverts, this could be the emoji for you.

It’s time for the moral argument at the end of the piece. Should we accept a frowning poop emoji or not? It’s hard to tell, and – Surprise! – that’s the real message. From its inception, the role of Unicode has been to create a universally-applicable code by which language can be transmitted reliably. Part of that reliability means that everything that gets entered into Unicode must remain there permanently, or threaten the integrity of the system.

When they agreed to take on emoji encoding, the Unicode Consortium took on the initial set of 625 emojis without question, and today issues like these are the result. The Consortium’s website (linked below) contains a guide on what may or may not make a good emoji, and a hefty portion of the page is dedicated to a sort of “do as I say not as I do” philosophy regarding previous emoji acceptance.

For example, while we have dogs available in both forward-facing and profile-view formats, the Consortium says this isn’t reason enough to have a forward-facing equivalent of every animal emoji. Similarly, the existence of Japanese buildings, landmarks, and cultural items does not justify the inclusion of those from other countries and cultures.

Don’t get me wrong – I think the inclusion of emoji in Unicode is wonderful, maybe one of their smartest decisions in the modern era (if you don’t think I’m bluffing here by pretending to know shit about Unicode’s recent non-emoji history, I don’t know what to tell you). Emoji are more than the cute little pictures used by teens and tweens on the Facechat and Snaptime that we gave them credit for years ago. In her book Because Internet, linguist Gretchen McCullough presents the idea that emojis instead act as gestures and visual carriers of semantic information not easily depicted in text. Having that critical communicative information available across platforms allows for more accurate communication to blossom.

That said, the growth of emoji as a form of communication has largely been organic. If even the inventor of the system couldn’t imagine that faces would be critical to emoji’s success, how could anyone be expected to know how the depiction of the smelliest of the group would change its meaning (and ours) ten years later?

However you feel about it, can we at least get SCREAMING TYPOGRAPHER PILE OF POO added to the system? I’ll write up the proposal now.

Read More:

- 2018: The Year of Emoji Convergence? by Jeremy Burge for Emojipedia

- Because Internet by Gretchen McCullough

- History of Unicode from unicode.org

- Members of the Unicode Consortium

- Sh*t Is Hitting the Fan Over the New Poop Emoji by Madison Malone Kircher for Intelligencer (New York Magazine)

- The WIRED Guide to Emoji by Arielle Pardes for WIRED

Article image altered from EmmanuelCordoliani’s Poop_Emoji.png from Wikimedia, licensed with Creative Commons-Share Alike 4.0. This image is thereby published and distributable by the same license.