When the Soviet Union fell in 1991, its 13 constituent republics declared independence, most of them free from Russian governance for the first time in well over a century. What had once been a neatly-organized collection of thirteen governments, republics in name but more similar to U.S. states in practice, now became a set of disentangled and totally-free nations.

At its geopolitical nadir, the Soviet Union managed to extract significant international power from its diverse mixture of nationalities and communities, having welded them together in the interest of advancing its Marxist-Leninist cause. Officially, the Soviet Union was purpose-over-people; its citizens were not Russians, Kazakhs, or Ukrainians, but Soviets, refuting the legacy it had inherited from the Russian Empire it succeeded in the 1920s.

As an empire, Russia’s ethnic composition was predominantly Russian, but its imperial fringes were a collection of grand, multiethnic marches. These (sometimes quite large) periphery zones are somewhat comparable to the outer territories of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, whose borders kept the slavic ethnic Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenians, Croatians, and Serbians locked in a state governed by predominantly Austrian and Hungarian officials and interests.

In other words, while the more urbanized core of Western Russia was mostly made up of ethnic Russians, everything else was a mishmash of racial and ethnic groups, from the Finns, Karelians, and Estonians in the northwest and Ukrainians and Moldovans in the west, to the southwestern Armenians, Azeris, and Georgians, and the predominantly-Muslim central asian groups to the south.

These are some of the largest ethnic groups of the Russian empire, but the list is expansive. Mountainous regions like the caucasus play host to an extraordinarily diverse array of ethnicities, from the Chechens and Ingush to the Ossetes and Avars. Similarly, the Eastern reaches of Siberia and the Russian Far East are populated largely by peoples native to those areas, including the Tuva, the Sibir, and the Ainu.

As with any country, the level to which minority groups in Russia became integrated with the majority group is variable. People from the mostly-Slavic western regions may have had more in common than those from the Caucuses, where Orthodox Christians still likely found more shared history and culture with the Russians than their Muslim neighbors. Understandably, the Russian Empire became no stranger to the occurrence of ethnic uprisings. Georgians, Turkic Bashkirs, and other minority groups regularly rebelled against Russian rule. Owing to the absurd size and military power of the Empire, though, none of these rebellions found considerable success.

When the Russian Empire fell amid the 1917 Russian Revolution, the Soviet Union took over. While a few territories previously held by the czar (mostly Finland) managed to leave the Russian realm, most would either stay or be pulled back in. Where the Russian empire was titularly and openly Russian, though, the Soviet Union pled its values as a country beyond ethnicity, where Russians, Kazakhs, and Latvians alike were Soviets first.

After the collapse, the ethnic groups whose names had been tied to Soviet Republics found themselves citizens of new ethnostates, nations designed with one racial-cultural group in mind. But the Soviet Union’s thirteen individual republics represented only a fraction of its ethnicities, and transitioning to a geopolitical order (officially) divorced from an ethnic focus to one driven primarily by identity meant acknowledging that, while some cultural groups would receive their own nations, the rest would live in those of another.

Owing in part to its multiethnic identity, many of the interethnic conflicts that preceded and succeeded the communist conglomerate would either cool of their own accord or be forcibly calmed by the Moscow administration. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, though, when the USSR’s cracks had begun to show and the thirteen Soviet republics edged closer to becoming independent republics, those conflicts began to heat up.

The Geographical Angle

In culturally-homogenous regions, where neighboring settlements all belong to the same ethnic or cultural group, borders might act as an uncontroversial clarifying agent of descriptive value; these people live here. In more heterogeneous regions, especially areas of complex and mountainous geography, drawing borders becomes more difficult. Members of separate ethnic groups often live beside and among one another in a way that makes legally distinguishing between their lands nearly impossible. Surprisingly, huge sweeping empires more interested in digesting territory than demarcating it don’t ease the job for those who eventually end up doing the line-drawing.

The Soviet Union in concert was Russia and twelve other republics, divided between Eastern Europe, the Caucasus mountains, and Central Asia. While Central Asia has not been without post-Soviet conflict, this piece focuses primarily on breakaway republics in Eastern Europe and the Caucuses.

The former Soviet Republics of Eastern Europe are Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova. While Belarus maintains a historically close relationship with the Russian Federation, its sister republics haven’t been on as friendly terms. The Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania joined the US-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2004, and internal political movements in Ukraine have pushed the country further in that direction. What once was a firmly-communist iron curtain has now mostly fallen to a system of strong allegiance to the west.

Broadly, the Caucasus mountains, one of the widely-accepted borders between Europe and Asia, also form one of the most politically-contentious regions on Earth. The area’s heavily mountainous geography and long history as a frontier zone between the Russian, Ottoman, Persian, and Byzantine empires led to an equally-long history of ethnic strife and conflict. Exacerbating already harsh racial and cultural barriers, the Caucasus also has the pleasure of being one of few areas on Earth where contrasting Muslim and Christian populations of equal conviction live side-by-side.

While each of the post-Soviet conflicts is similar to its cousins in one way or another, each is a wholly-unique situation driven by local history, geography, and culture.

The remainder of this piece will attempt to dissect each of the major conflicts and aim for a general understanding of the conditions that created them. These are the largest incidents of racial strife in the post-Soviet world, but the list is not conclusive. Likewise, this piece will not attempt to choose to identify heroes or villains. As always, where race or ethnicity is concerned, it’s important to understand that the actions of governments, militaries, and organizations are not the actions of an ethnic group as a monolith. Each of these conflicts involves the suffering of people not in control of their geopolitical situation.

Abkhazia and South Ossetia

Abkhazia is a coastal region in northwestern Georgia, bordering Russia and the Black Sea. First annexed by Russia in 1864, Abkhazia enjoyed brief revolutionary independence before a Soviet invasion fit the country into a smaller box as the Abkhazian Soviet Socialist Republic, a subdivision of the Soviet Union. Ten years later, in 1931, Moscow decided Abkhazia wasn’t cut out to be a full republic, and diminished its status to that of an ‘autonomous republic’ within Georgia. It’s republics all the way down.

During the Soviet era, Abkhazia and Georgia coexisted in relative peace, but in the early 1990s, tensions rose as the Soviet Union disintegrated and its constituent republics began declaring their independence. While Abkhazia was part of the USSR, its territorial status outside was something of a technicality — as long as its leaders eventually defer to Moscow, it doesn’t matter as much who the middle men are. With an independent Georgia, though, Abkhazian leadership reports directly to a Georgian government, which reports to no one.

Amid declarations of independence, Abkhazia throws its hat into the ring: if Georgia is free of Soviet leadership, they are too. The two republics go to war in 1992, and the rebel Abkhazians win. Before the rebellion, about half of Abkhazia’s population was made up of ethnic Georgians. By the war’s end, most Georgians fled, with some ethnic Russians and Armenians following.

The war between Georgia and Abkhazia came to a tenuous standstill in 1994 with a cease-fire brokered by Russia and supported by Russian troops. Since, Russia has maintained a strong and consistent military presence within the breakaway republic.

Just 85 miles inland, another breakaway republic creates stress in Georgia. The would-be Republic of South Ossetia shares something of a similar history with Abkhazia. The two were both created as autonomous zones within the Georgian SSR, and both declared independence from Georgia in the early 1990s, with each managing considerable success in their attempts to detach.

Like Abkhazia’s rebellion, South Ossetia’s attempt at independence ended in a Russian-brokered ceasefire. Georgia retained control of parts of South Ossetia, but the region’s new government managed to hold on to a considerable portion of the territory post-ceasefire.

Temperatures rose between Georgia and Russia in the mid-2000s, when Georgia formally demanded that active Russian peacekeepers register for visas and Russia withdrew the troops it had based in the country since 1991.

In November 2008, Georgia began an attempt to resecure South Ossetia, sending soldiers into the region. Russia responded by sending its own military and opening a campaign of airstrikes over South Ossetia. Tanks rolled south from Russian North Ossetia. The event, the Russo-Georgian War, lasted twelve days and ended in Georgian defeat, with approximately 15,000 Georgians forced from their homes.

Today, according to the BBC, “the local budget is heavily reliant on funding from Russia, there are few job opportunities and South Ossetia is struggling to get on its feet.”. The author, Sergei Goryoshko, attributes the existence of a modern, “militarily-emboldened Russia” to the outcome of the 2008 war.

While Russian troops were removed from Georgia proper in 2007, the country maintains a significant military presence in both South Ossetia and Abkhazia. In early 2008, prior to the Ossetian conflict, the United Nations corroborated a Georgian accusation that Russia shot down an unmanned drone over Abkhazia. Russia soon thereafter bolstered their military forces in Abkhazia, going against the French-organized ceasefire; Russia argued its forces were necessary for railroad maintenance.

In Abkhazia, the region that previously served as a mixed homeland to Abkhazians, Georgians, Armenians, and Russians, has been accused of catering specifically to its native Abkhazians alone. Georgians in the region suffer disenfranchisement and, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, have been “pressured to take on Abkhaz names and identities”. A presidential election in the region was postponed in 2019 after an opposition candidate became sick, allegedly having been poisoned. The candidate, Aslan Bzhania, later went on to win a majority of the votes. He currently serves as the country’s president.

Crimea and Eastern Ukraine

Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea was big-time news. If any of these conflicts were familiar to you pre-2020, there’s a good chance it’s this one. The annexation was a rare example of paramilitary conquest perpetrated by a major power in the 21st century, and the ensuing diplomatic crisis sent the western world reeling in an attempt to respond to Russia’s interference with Ukrainian sovereignty.

Crimea’s history is long and varied. The region, a peninsula in the Black Sea only narrowly-connected to the Ukrainian mainland by a thin collection of swampland, was variously ruled by Romans, Avars, Tatars, Mongols, and Ottomans before it was colonized by the Russian Empire under the leadership of Catherine the Great.

With the fall of the Empire and the rise of the Soviet Union, Crimea was placed under the legal jurisdiction of the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic until 1954, when the Kruschev administration transferred it to Ukraine. When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, an independent Ukraine retained the Crimean peninsula.

Unlike some of the regions described in this piece, the relationship between Ukraine and Crimea following the fall of the Soviet Union wasn’t particularly tense. While Crimea retained a strong community of ethnic Russians who spoke the Russian language, they did not conflict openly with the Ukrainian government.

In the early 2010s, though, the people of Ukraine began to break with their pro-Russian government in an attempt to call for closer relationships between Ukraine and Western Europe, with some arguing in favor of Ukrainian membership in the European Union. This movement culminated in the 2013-2014 Euromaidan Protests, which resulted in the ousting of Ukraine’s president, an early presidential election, and the freeing of previous Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko from prison.

While Euromaidan’s initial successes signaled to some the opening of Ukraine to participation in dialogues with the west, they also signaled a threat to neighboring Russia. In 2014, unidentified troops began appearing in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. The soldiers occupied military checkpoints and important facilities, and operated as an armed, military presence in the region. Known for their Russian combat uniforms but lack of identifying insignia, they became known in the media as “little green men”.

The Russian government’s formal position on the soldiers occupying Crimea and Eastern Ukraine was that they were neither Russian nor under the authority of the Russian Federation. Notably, though, Russian President Vladimir Putin would later go on to offer military commendations to commanders tied to the little green legion.

Shortly thereafter, on March 6th, the Crimean Supreme Council voted to join the Russian Federation, scheduling a referendum for ten days later. The referendum offered voters two options: join Russia, or readopt Crimea’s 1992 constitution, which involved significantly more autonomy for the peninsula. Maintaining the current regional order was not an option.

According to the Brookings Institute, “local authorities reported a turnout of 83 percent, with 96.7 percent voting to join Russia”. The assessment goes on to note that “the numbers seemed implausible, given that ethnic Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars account for almost 40 percent of the peninsula’s population”.

Indeed, later numbers from third-party observers identified a more realistic turnout of between 30 and 50 percent, with only a small majority of those opting for Russian annexation.

Beyond its significant ethnic Russian population, the Crimean peninsula is a geopolitical boon to Russia, offering a strategic staging post for trade and naval activity in the Black Sea.

Five years on, in 2019, an evaluation in the Washington Post cited polling data that suggests the annexation remains popular in Crimea, even among the region’s non-Russian populations. But even if Crimea’s people feel comfortable under Russian administration, the existence of Russian Crimea falls in the shadow of the circumstances that created it: a referendum held under military occupation and without international observers.

Moreover, the conflict is not without casualties. According to the New York Times, “Russian authorities have transferred hundreds of prisoners and pretrial detainees in Crimea to Russian prisons, a violation of international law”.

Less publicized, the situation in Eastern Ukraine is different. While Russia backed pro-Russian movements in both regions, the Kremlin hasn’t gone as far as annexing Donbass (the regional name for the Donetsk Basin, where most of the conflict has occurred). The Russian Federation continues to support militant groups in the region, but it hasn’t floated a plan for annexation. Writing for Foreign Policy, Tatiana Stanovaya argues that, unlike the motivations behind Moscow’s annexation of Ukraine, Russian military activity in Donbass is meant to provide leverage for the Putin regime in Ukraine, allowing the Russian government bargaining power in response to growing anti-Russian sentiment in the country.

Today, the state of affairs in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine is unlikely to change. Ukraine lacks the military power to significantly contest either of Russia’s incursions, and despite denunciations by NATO and Western powers, Russia has yet to take significant enough damage to convince a change in action. Moreover, there’s scant evidence that the locals, at least those in Crimea, are actively fighting for such a change. Still, it may be important to remember that a victory for Russia and a perceived victory for the region’s ethnic minority can remain a loss for democratic representation and self-determination. The conditions of an election are always as important as the results of an election.

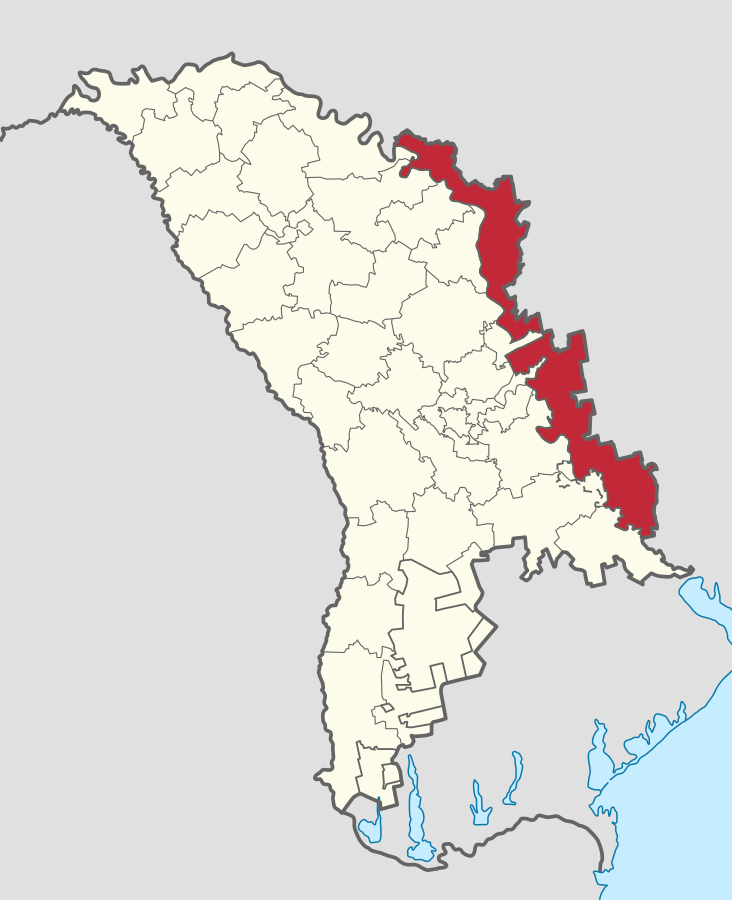

Transnistria

Transnistria, also known as Transdniestria, also known as the “Preidnestrovian Moldavian Republic”, each more difficult to pronounce, is a narrow breakaway republic wedged between the borders of Moldova and Ukraine. Each of the territories included in this piece is a scar of the Soviet Union, but this is the one that bears the most resemblance to its predecessor. Most articles about the territory can’t resist commenting on how Transnistria looks like a resuscitated province of the USSR.

The comparisons are mostly aesthetic. The country hasn’t done away with Soviet iconography in the same way that its neighbors have. Its flag still bears the familiar hammer and sickle of the communist Soviet Union. In spite of that, though, Transnistria isn’t communist. Officially, it’s a presidential democracy. In practice, the strength of that democracy has been challenged — a 2003 report by the United States department of state noted that in one northern region of the country, “103.6 percent of voters cast ballots” for the candidate who would go on to win the election. Opposition candidates have been officially discouraged and banned from running for the office of President.

Like most would-be republics featured in this piece, Transnistria’s most modern roots come in the late 1980s and early 1990s, at the fall of the Soviet Union. Similar to Crimea and Donbass, Transnistria’s population is largely composed of ethnic Russians living in a country (Moldova) with primarily a primarily non-Russian populace.

BBC reports that those who would build Transnistria were united, first, by “growing nationalist sentiments” in the Moldovan SSR just before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and then by a later move by Moldova to ban use of the Russian language, which most Transnistrians spoke.

Transnistria officially declared its independence in 1990, and tensions flared into full military confrontation in March of 1992. A ceasefire was declared in July, but not before at least 1,000 people had been killed.

The situation following the conflict has been de facto independence for Transnistria. The Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic officially governs its own territory, but not without substantial outside support. National Geographic reports that the region’s perimeter is patrolled by around 1,200 Russian peacekeepers tasked with enforcing the ceasefire. That foreign garrison has put strain on relations between Moldova and its breakaway cousin.

Today, Transnistria maintains its semi-Soviet aesthetic and its people live somewhat normal lives. Officially, the republic only has recognition from Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Artsakh, its comrade scars of the Soviet Union. Behind the scenes, though, the Republic relies on considerable support from Russia, whose military and civil aid provides for the region’s hospitals, school, power, and pensions. Russia doesn’t officially recognize the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic, but its direct support keeps it alive.

Nagorno-Karabakh

The most recent conflict to erupt in the post-Soviet sphere is an ongoing series of clashes in the south Caucasian territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, a collection of mountainous terrain claimed by both Azerbaijan and the ethnically-Armenian breakaway state known as the Republic of Artsakh. The region, which is internationally recognized as Azeri territory but internally governed as an independent state and populated almost exclusively by ethnic Armenians, has a deep history of conflict and opposing claims.

The area has a long history, changing hands frequently between nearby powers, variably belonging to Persia, Armenia, the Byzantine Empire, and Russia. The latter acquired the region in 1813 when the Czar formally annexed the territory of the Karabakh Khanate. Nagorno-Karabakh remained a piece of the Russian Empire until its dissolution in 1918 amid the Russian Revolution that gave rise to the Soviet Union. Independence of the three major South Caucasian nations, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, was short-lived, as Bolshevik troops entered the region three years later and recaptured most of the Russian Empire’s Caucasian territory.

In organizing their southwestern frontier, the Soviet government originally allocated the Nagorno-Karabakh territory to the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. Shortly thereafter, though, Soviet General Secretary Joseph Stalin, of Joseph Stalin fame, changed course, making it an autonomous administrative region of Azerbaijan. At the time, according to National Geographic, Nagorno-Karabakh’s population was 94% ethnic Armenians. Stalin’s decision, allegedly directed at currying favor with the predominantly-Muslim SSRs in the Soviet periphery, would cement the culturally-Armenian region as an integral piece of Azerbaijan through the remainder of the USSR’s tenure.

As with conflicts elsewhere, overt tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan cooled during the Soviet period, largely attributable to the status of both nations as players secondary to the significantly more powerful Moscow government. As signs of fracturing became clear in the late 1980s, though, tensions again rose over the status of Nagorno-Karabakh.

The greatest conflict between the two countries began in 1988, predating the collapse of the Soviet Union by a few years. Ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh petitioned to join the Republic of Armenia, prompting an Azeri assault that spawned the six-year Nagorno-Karabakh War. By its end, a Russian-mediated ceasefire left Nagorno-Karabakh and seven surrounding districts of Azerbaijan under the authority of Armenia. The conflict left at least 30,000 dead and created as many as one million refugees, including 600,000 Azerbaijanis who fled mostly from the occupied districts on the fringes of Nagorno-Karabakh proper.

The ensuing peace has been tenuous, punctuated by incidents of violence in the region. Following the signing of the ceasefire, an international diplomatic body known as the Minsk Group was created, led by Russia, France, and the United States. The three nations have struggled to make any progress in the brokering of a lasting peace deal.

To Azerbaijan, the continued existence of Armenian troops in and around Nagorno-Karabakh violates the territorial integrity of the Azeri state. To Armenia, Azerbaijan governing over Artsakh represents a potential existential emergency to the over 150,000 ethnic Armenians who live there. Racial and cultural Armenians were previously targeted by the Ottoman Empire during the Armenian Genocide, an extermination campaign taking place in the early 20th century that left approximately 1.5 million Armenians (at least 50% of those living in Turkey) dead.

Understanding the parties to the current conflict can be difficult, given that media portrayals and historical overviews tend to label Armenia and Azerbaijan as belligerents. Despite Armenian presence in the region, the principal conflict is between Azerbaijan and the Republic of Artsakh, an internationally-unrecognized state encompassing the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Proponents of Artsakh’s independence note that the country’s existence was proclaimed in 1991 as the Soviet Union was falling, arguing that its declaration of sovereignty predates the official dissolution of the USSR, and that an independent Azerbaijan does not inherit the authority of the Soviet Union.

Internally, a functionally-independent Artsakh has made strides in democratization. The US-based non-profit Freedom House labels the country “partially free”, placing it evenly between the levels of freedom attributed to the partly-free Armenia and the “not free” Azerbaijan. A referendum held to approve the drafting of a 2006 constitution and the official adoption of the “Republic of Artsakh” succeeded with 90% of voters voting in favor. Total electoral turnout was measured at around 76% of registered voters, and the referendum was observed by over 100 international organizations and 30 countries.

A four day war between Armenia and Azerbaijan left some 350 people dead before the provision of a Russian-brokered ceasefire. Both sides claimed victory.

Since that fight, the region had mostly returned to the status quo created by the ceasefire. Tensions would stay relatively low until September 2020, when a series of attacks escalated into full military conflict. Both sides accuse the other of initiating the conflict. As of writing this piece, the military campaign is ongoing despite two failed ceasefires organized by Russia and France. Some have taken to labeling this conflict the “Second Nagorno-Karabakh War”.

The conflict between Artsakh, supported by Armenia, and Azerbaijan is dangerous and, on its own, threatens the lives of potentially thousands in the region (at least one thousand were dead when this piece was written). The more prominent concern, though, comes from exponentially-more powerful regional allies. Azerbaijan, whose people are ethnically Turkic and religiously Muslim, has built a strong military alliance with Turkey, a country whose anti-Armenian policies may predate its pro-Azerbaijani proclivities. Armenia, meanwhile, maintains a longstanding alliance with Russia; the two nations are obliged to aid each other in the event of foreign attack, and Russia has military bases and assets within Armenia.

Allegations that international intervention in Nagorno-Karabakh has already begun are plentiful. Azerbaijani allegations of foreign fighters operating alongside Armenians are so-far unproven, as are some Armenian suggestions that Turkey is deploying its own troops to the region, though claims that the Turkish government has led Syrian infantrymen into the country to fight on its behalf appear to be supported by evidence, and the Turkish military has provided significant arms support to their ally.

Nearby, Iran has also acted as an observer to the conflict, and some have expressed concerns that Iranian involvement could be forthcoming.

According to Vox, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has advocated for “mutual concessions” with Azerbaijan, but Azeri president Ilhalm Aliyev remains on the offensive, proclaiming “Nagorno-Karabakh is our land” and adding “This is the end. We showed them who we are. We are chasing them like dogs.”

Amid harsh rhetoric and deadly battle, outside analysts worry the fighting is destined to grow. For Vox, Alex Ward writes “while experts hope for a diplomatic solution to the decades-old conflict, or at the very least another ceasefire, many fear the fighting this time will continue until either Armenia deals Azerbaijan a militarily decisive blow or Azerbaijan reclaims much or all of Nagorno-Karabakh and its surrounding regions.”. The New York Times cites official reports that claim that more than half of the people in Nagorno-Karabakh have fled their homes amid fighting.

Azerbaijan maintains that Nagorno-Karabakh is Azerbaijani territory, a claim corroborated by international recognition. Armenia and the Republic of Artsakh argue that the collapse of the Republic could be the death knell of its Armenian population, invoking both the memory of the Armenian genocide and the divisive rhetoric of Azerbaijani leaders who may see ethnic Armenians as an internal enemy. Appeals for independence or regional self-determination have mostly fallen upon deaf ears, with the international community arguing that the situation in Artsakh cannot be determined by anything other than a mutual agreement signed by the governments of both Armenia and Azerbaijan. So far, that agreement seems unlikely to come soon.

Read More

- 2008 Georgia Russia Conflict Fast Facts by CNN

- Abkhazia in Encyclopedia Britannica

- Celebrating a nation that doesn’t exist by Sarah Reid for BBC

- Crimea: Six years after illegal annexation by Steven Pifer for the Brookings Institute

- De facto states and democracy: The case of Nagorno-Karabakh by Pål Kolstø and Helge Blakkisrud, punished in Communist and Post-Communist Studies

- For Nagorno-Karabakh’s Dueling Sides, Living Together is ‘Impossible’ by Anton Troianovski for the New York Times

- Frozen fragment, simmering spaces: The post-Soviet de facto states by John O’Loughlin (University of Colorado-Boulder) and Gerard Toal (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University)

- How the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has been shaped by past empires by Erin Blakemore for National Geographic

- How to Disappear a Country by Amie Ferris-Rotman for The Atlantic

- Putin marks 5th anniversary of Russia’s annexation of Crimea by Vladimir Isachenkov for the PBS via the Associated Press

- Putin Reclaims Crimea for Russia and Bitterly Denounces the West by Steven Lee Myers and Ellen Barry for the New York Times

- Russia Committed ‘Grave’ Rights Abuses in Crimea, U.N. Says by Nick Cumming-Bruce for the New York Times

- Six years and $20 billion in Russian investment later, Crimeans are happy with Russian annexation by Gerard Toal, John O’Loughlin, and Kristin M. Bakke for the Washington Post

- South Ossetia: Russia pushes roots deeper into Georgian land by Sergei Goryashko for BBC

- The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, explained by Alex Ward for Vox

- The crisis in Crimea and eastern Ukraine in Encyclopedia Britannica

- The Fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh is about Local Territories, Wider Rivalries by Gerard Toal, Kristin M. Bakke, and John O’Loughlin for the Washington Post

Images

- 2014 Stepanakert, Monument My i Nasze Góry

- Photo by Marcin Konsek for Wikipedia

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. No changes made.

- United Nations map of Georgia, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia

- Published by the United Nations Cartographic Section, Public Domain

- Map of the 2014 Russo-Ukrainian War

- Image by Wikipedia user Niele

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. No changes made.

- Transnistria in Moldova

- Image by Wikipedia user TUBS

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. No changes made.

- Nagorno-Karabakh Map

- Image by Wikipedia user Achemish

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. No changes made.