Amid the relative chaos of the 2019-2020 coronavirus outbreak, folks working from home or out of work completely may find themselves so detached from a regular schedule that the days of the week become trivial. What day is it, anyway, if all of them seem to blend together? This piece won’t tell you that. It can’t. Technology isn’t there yet. More realistically, it is there, but it’s on your phone, probably right at the top when you turn it on. It’s simple, and we’ve figured it out together. So now, let’s ignore that question and talk about how the days came to be.

Days have been here since the earth first spun around the sun – you knew that. From a human perspective, they’re probably the oldest unit of time in existence. Hours are complex and arbitrary, and years are less arbitrary, but much more complex. For most of human history, the day was the only important unit of time. When survival is the game and Ogg is your name, the concept of a week doesn’t really come through as well as “time to sleep” versus “time to not sleep”.

Fast forward to the minor human innovation that was civilization and its mom, agriculture, keeping track of longer periods of time is now important. Understanding the chronological difference between the wet season and the dry season is life and death when there are no more mammoths to hunt and you’re too attached to the decor in your living room to search for berries. So, civilizations concerned with crop growth and agricultural routine developed the first calendars, going off of the best tellers of complex time available: the moon and the sun.

Telling time by the moon is easy. It goes through distinct visible phases that repeat every four weeks or so. Keeping an eye out for that waxing gibbous moon is a treat of its own. Becoming a level four moon master does have its drawbacks, though, where time is concerned – the moon is kind enough to offer a clear and constant sign of the passage of time, but the moon is not the Lord of time itself. That’s the sun. Sure, our lunar pal has some influence over the waves, but when our concern is the seasons, it’s all about the sun.

The problem laid bare: lunar months (the amount of time between either full moons or new moons depending on civilization and where they’re at in the Twilight mythos) don’t quite fit evenly into the 365 ¼ (ish) day span of time we now know as a solar year. So, naturally, early timekeeping based on the easily-predictable phases of the moon was slightly flawed. A calendar that used the moon exclusively would find its months slowly slipping into other seasons unless the authority in charge of that calendar regularly added intercalary time to retune it with the solar year.

This is how the early Roman calendar worked. According to ancient Roman myth, the earliest-attributed Roman calendar was drawn up by Romulus, one of the founders of Rome, seven or eight hundred years before Jesus. It’s worth noting that the same mythos holds that Romulus and his twin, Remus, were both raised by a she-wolf. Who knows, maybe “moon howling” as a first language translates well into the drafting of a lunar calendar. I’m all in on Romulus.

Before we delve further into this critically Romulan invention, I should disclaim the idea that the early Roman calendar was the first, best, or only calendar of its kind. Civilizations around the world invented their own methods of agricultural and societal timekeeping. The difference is that the Roman calendar developed into the one we (in the Western world) use today, and that the other ones are harder to comprehend and would require rigorous research. You understand.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, this original Roman calendar started with the month of March and included ten months, six with thirty days and four with thirty-one. Its 304-day tenure ended in December. For those counting, that’s 61 (or so) days off of the calendar we use today. But, historians figure the calendar didn’t leap immediately from December 31st to March 1st. Instead, at the end of December, the Romans entered a winter period of indeterminate length, a sort of mystery season, or a more hardcore interpretation of Groundhog Day, where the part of Punxsatawney Phil is played by the King of Rome.

This wacky, fun tradition of mystery winter wouldn’t last long, though. The second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, filled the gap with two additional months, January and February. The previously-flawed calendar was fixed and now boasted 354 days. Britannica also explains that January was given an extra day to assuage Roman fears of even numbers (scary). February, however, was left with an even number of days, which Romans were fine with because that month was given to the celebration of the “infernal” gods of hell. Being born in February never felt so great. Hail Hades Pluto, I guess.

The next innovation came with the Roman Republican Calendar launched a couple centuries after its predecessor. This time, the calendar was 355 days (closer!!) long. February had its 28 days, and the rest were given either 29 or 31 (remember: even numbers are scary as hell). 355 days isn’t super far off our current 365.25, but it’s far enough off that the months and seasons started to slip. To account for this, the Romans added an intercalary month, Mercedonius, that occurred every other year. It’s sorta similar to our modern leap day, except in that Mercedonius was insane.

Today, every four years, we celebrate a leap year and add a single day to the calendar at the end of February (big asterisk — we’ll get to this later). In Mercedonius, the Romans added twenty seven or twenty eight day to their calendar, also in February, but notably not at the end. Instead, Mercedonius started the day after February 23rd, and usually overwrote the rest of the month. Imagine how obnoxious the leap year babies would have been.

Britannica explains that this period of intercalation was the responsibility of the Pontifices, a body of Roman religious authorities from which the Pope takes his Twitter handle. The intimate reasons behind the length of the intercalation were a closely-kept secret, but corruption and ignorance led to what Britannica calls “seasonal chaos”.

The absolute insanity of the Roman calendar’s design, coupled with its need for biyearly tune-ups by a council of astrologists, resulted in more than a few problems. By the time Julius Caesar ascended his throne in the late BCE years, the Roman calendar was three months ahead of the solar calendar, so Caesar, advised by an Egyptian astronomer, adjusted it, bringing it to an even 365.25 days. Each month in this new Roman calendar was either 30 or 31 days long, except February. It was absolutely imperative that February retain its spooky, uneven number of days. So, naturally, when the leap year occurred every four years, it didn’t add a February 29th (that would have been stupid). Instead, the Romans had two February 23rds.

For simplicity, I’ve been using the English names of the months so far. The Romans knew them differently, because they had never heard of English. The first four took their names from Roman gods, Martius from Mars, Aprilis from Aphrodite, Maius from Maia, and Iunius from Juno. The remaining six months of the original calendar were equally creative, being named “Quintilius” for the fifth month, “Sextilis” for the sixth, and so on, through September, October, November, and December. The introduction of January and February rudely destroyed this pattern, but they were originally included at the end of the calendar. January took its name either from the Roman god Janus or from Juno (again, creativity was key), and February from a period of celebration it overlapped. Later, the Roman senate would rename Quintilius “July” after Julius Caesar himself, and Sextilis “August” after his adopted son and successor, Augustus.

So now we’re at 365 ¼ days. That’s how long our current calendar is, so we’re good, right? Obviously not, I’m being condescending. We know a year isn’t exactly 365 days, but it is pretty exact, right? One extra day every four years isn’t bad. But remember: the length of a solar year is the amount of time the Earth takes to revolve around the sun, and the sun feels no obligation to follow our rules. It’s the sun. It’s very hot. The exact amount of time in a revolution, according to NASA, is 365 days, 5 hours, 59 minutes, and 16 seconds. The extra minutes and seconds may seem trivial, but any deviation matters over time. From the adoption of the Roman Republican calendar to the reign of Caesar, the calendar had fallen a few months behind. Caesar’s more perfect calendar wasn’t as bad. From its adoption some 40 years before Jesus to today, the calendar is only off by 13 days (14 in 2100).

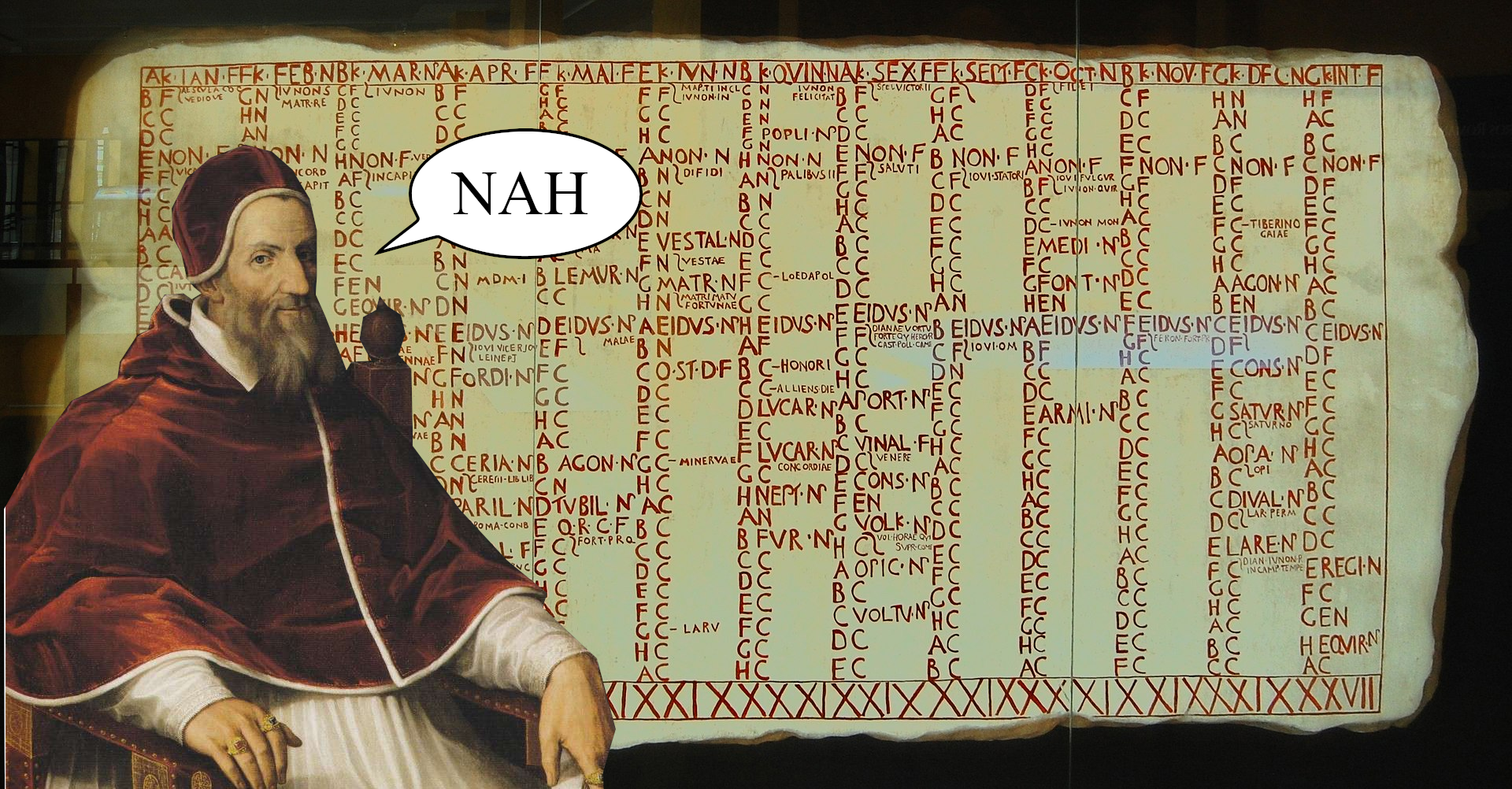

13 days isn’t a ton. In 1582, the Julian calendar was off by even less. But it was inaccurate, and this was the heyday of the Catholic church. The reigning pope, Gregory XIII commissioned an updated calendar to make up for lost time. This new calendar, the Gregorian Calendar, mimicked its predecessor in all ways but one. The leap year, which still occurred once every four years, would mysteriously disappear every hundredth year, meaning while 1896 had 366 days, 1900 would only have 365. This, though, was still too inaccurate for Gregorian standards, so a smaller asterisk was added: the leap year would occur every fourth year, except on every hundredth year, except except every four-hundredth year.

To use our example from earlier, in the Gregorian calendar, 1896 and 1996, both being leap years, each have 366 days. Because 1900 marks a period of one hundred years, though, it is exempted from being a leap year, and it instead maintains a balance of 365 days. The year 2000, though, is a spectacular exception in that it’s a four hundredth year, meaning it is a leap year with 366 days. This can be super confusing to everyone currently alive, because this 2000 exception means we have never experienced a skipped leap year. The last one happened in 1900, and the next one will occur in 2100. Likewise, 1600 was a leap year, and 2400 will be as well.

The adoption of the Gregorian calendar was pretty quick among the Catholic nations of Western Europe. The Protestant states were slower, with an adoption period lasting over seventy years (England in 1752, Sweden in 1753). Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1873 and China in 1912. The Eastern Orthodox Christian states of Eastern Europe, by contrast, took longer than anyone, owing, at least in part, to bad blood going back to the Catholic-Orthodox schism of 1054. The Soviet Union adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1918, at the tail end of the Russian Revolution. Greece waited until 1923.

Today, almost all countries use the Gregorian calendar in some capacity. Ethiopia, Iran, Afghanistan, and Nepal are the only four to have continued their resistance to Gregory’s meddling, after Saudi Arabia left their bandwagon in 2016.

Having freshly unlocked the secrets of the calendar, we all agree that we didn’t even notice that I haven’t written anything about the days themselves. That’s for next time. Watch for the second part of this piece, due some time before February 23rd. The second one.

Read More

- Calendar: The early Roman calendar in Encyclopedia Britannica

- The Evolution of the Roman Calendar by Dwayne Meisner

- Gregorian calendar in Encyclopedia Britannica

- Julian calendar in Encyclopedia Britannica

- We’ve been using the Gregorian calendar for 434 years. It’s still bizarre. by Brad Plumer for Vox.

Title Image

- Background: Reproduction of the Fasti Antiates Maiores by Wikipedia user Bauglir, distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International. Changes were made.

- Foreground: Pope Gregory XIII, author unknown. Public domain. Sourced through Wikipedia.

- According to the terms of the ShareAlike license, this image is available for reuse without permission. I hope you can find a use for it.